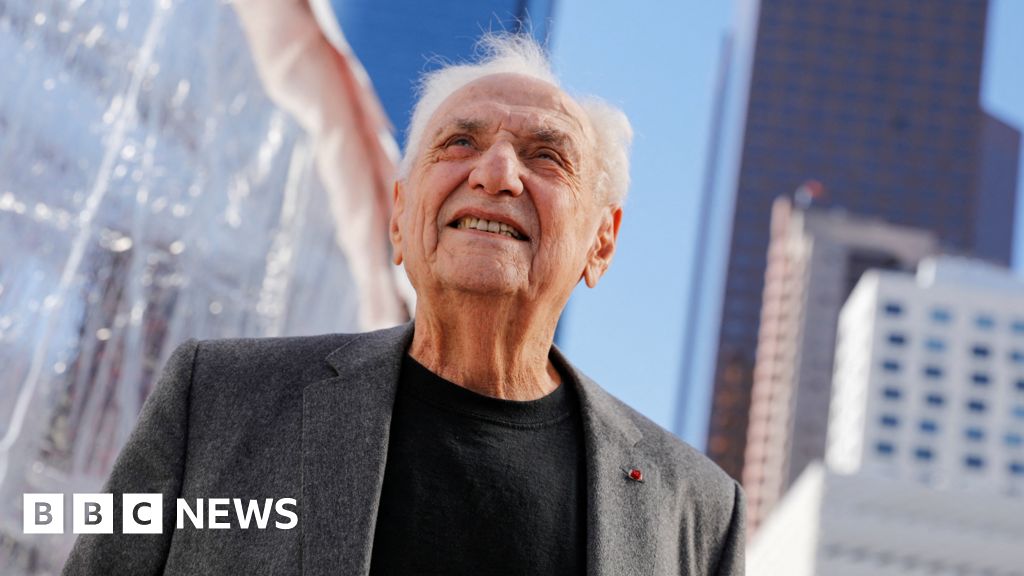

Image copyright

Getty Images

The cost of the government’s efforts to combat the coronavirus pandemic has risen to £123.2bn, according to latest estimates from the government’s independent economics forecaster.

The Office for Budget Responsibility’s previous estimate was £103.7bn. The increased cost of the government’s furlough scheme is the main cause.

It now expects annual borrowing to equal 15.2% of the UK economy.

That would be the highest since the 22.1% seen at the end of World War Two.

The extra spending has pushed the deficit identified for 2020-21 in the OBR’s reference scenario, which it says is not a formal forecast, above the 15% in 1945-46, which included VE Day.

Borrowing for this year is calculated to be £298bn, up £26bn on the first attempt to calculate the impact of the pandemic a month ago.

This is mainly because of the extra costs of extending the furlough scheme to the end of July.

Including the extra extension of a modified scheme until October could add an additional £20bn, depending on the as yet unannounced details of the scheme.

What other costs are there?

The OBR also reckons that taxpayers could end up footing a big bill for bad bank loans.

Some £5bn in taxpayer cost from unpaid loans to banks is included in this financial year.

An extra £1bn is already earmarked for the cost of welfare, mainly spiralling claims for Universal Credit.

The OBR’s last official forecast at the Budget anticipated annual borrowing by the government of £55bn, rather than £298bn, says BBC economics editor Faisal Islam.

The difference in just two months – the result of the pandemic and shutdowns – is a £127bn hit to the money that government takes in, mainly expected tax revenues, and £119bn in extra spending to support the economy over the year, our editor adds.

Why it matters

As Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, explains, the extra spending is “fantastic good news” for ordinary people at the moment, because it means that the government is paying many people’s wages when they might otherwise be struggling.

But he adds: “Beyond that, there’s a point at which people will have to start thinking, ‘How do we pay for all this?’

“That’s when it becomes relevant in a bad way further down the line. We will have to pay for it, either by taxes going up or by spending being cut.

“It’s a two-step process. In the near term, it’s helping people out, but there will be consequences in the future.”