By Lora Jones

Business reporter, BBC News

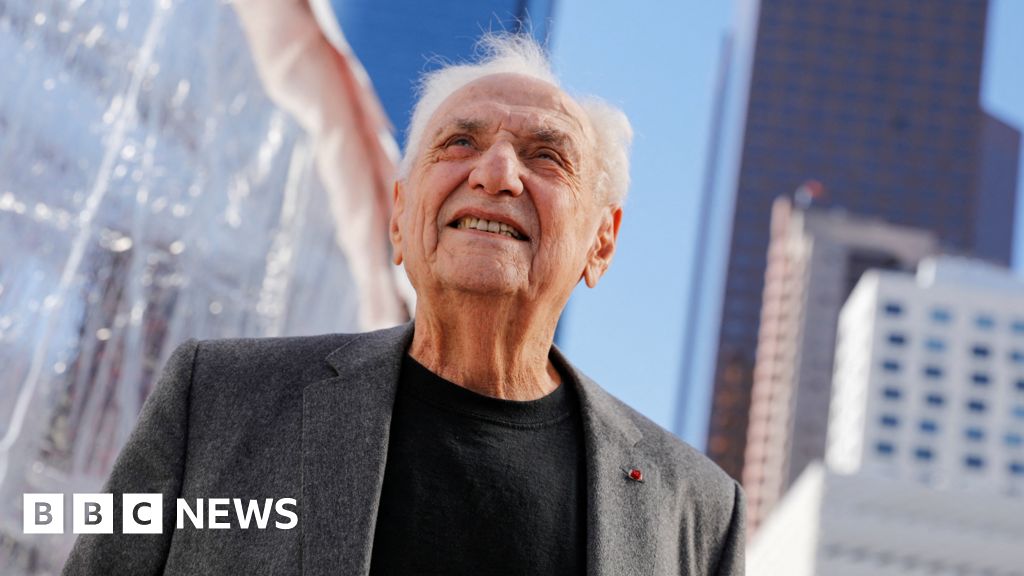

Mark Sealey has been digging graves for over four decades

The pandemic has transformed the world of work. From setting up a desk in the garden shed, to a loss of hours or income – few people’s working lives have been left unchanged.

This upheaval has left many questioning what they do and why they do it. As part of a series called ‘My Job‘ we investigate how different people find purpose in their daily work.

Mark Sealey digs graves for a living – although the more accurate description for his job is a sexton. He also maintains the grounds and graveyard at Wigston Cemetery in Leicestershire and assists at funerals.

How did you get into the job?

I knew a few guys [working] at the cemetery. There were a lot of bikers and hippy types in the maintenance sector and we were all into rock music – so it seemed like a natural transition to start working there too. It was a place where we all shared similar interests and wanted to work outside.

I also worked with a lot of ex coal-miners with injuries. They were used to using machinery and trenching and those skills were transferrable to cemeteries.

What does a typical day look like?

A normal day would involve grounds maintenance. But there’s always burials and those can come in at any time. At the start of the week we’ve got nothing, but by Friday we may have five. In a way, it’s like being on-call.

For burials, first thing, we go to where the family are going to congregate. We usually arrive any time from 07:30.

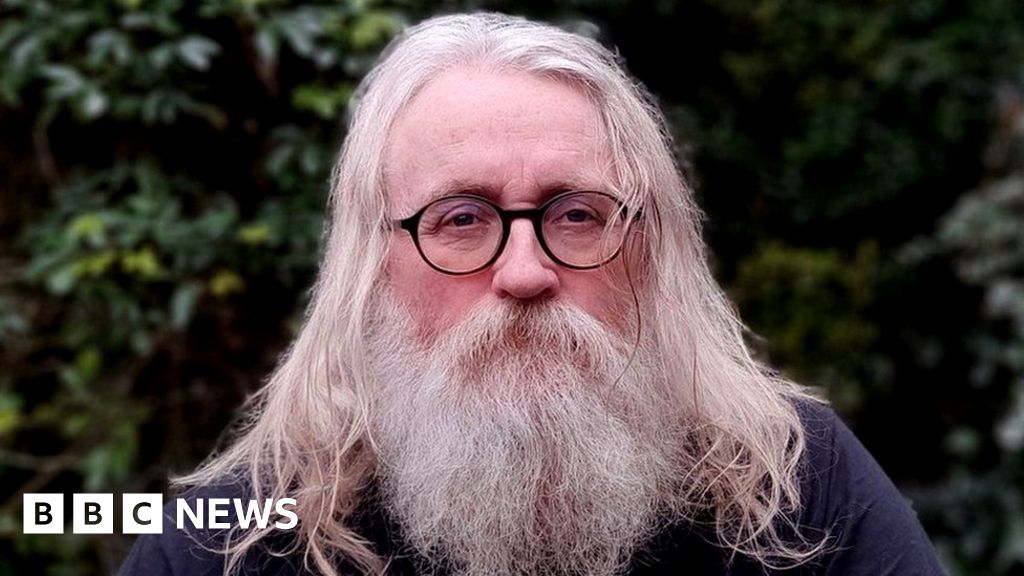

Mark works as part of a team at Wigston Cemetery

The paths are blown, rubbish bins emptied, we get [the area] ready and prepare for the funeral. The graves are usually prepared at least one full day before a burial. Then we drape the graves with cloth that’s shaped and comes from a proper supplier to fit them. Everybody gets the same treatment.

We always say people get an idea when they come to the burial [that] it’ll be like the one they saw on EastEnders – everything’s sunny and they’re all throwing daffodils in. But we’re dealing with nature and it’s unpredictable, so we can’t 100% guarantee how things might go.

Routes into cemetery work

- Direct application: You can apply directly for a job as a cemetery worker. You don’t need particular qualifications, although bosses may ask for GCSEs at grades 9 to 4 (A* to C), including English. Once you’re working, your employer will arrange for you to follow the Cemetery Operatives Training Scheme.

- An intermediate apprenticeship for horticulture and landscape operatives.

Source: National Careers Service

What do you enjoy most about the job?

I like being here. When I’m looking out the window, I’m yearning to be back outside.

It’s also a comforting role for people and you grow into it over time. If you’ve got an idea you want to make a difference, you can. I deal with all the tree-planting and can suggest different ones, or work with family members on how they want to commemorate their loved ones.

A sexton like Mark will discuss with bereaved families or friends how they would like to commemorate their loved ones

If you’re here for a while, you can see things change. We’ve planted everything from hawthorn and rowan trees, to cherries and pears. Seeing everything change and rotate is satisfying.

What are the biggest misconceptions?

I think the biggest one is that we don’t care – we’re just workers. I’ve been in this line of work for so long now, anyone doing a machinery-dependent job like this, we’re all conscious of the fact the machine we’re using makes a mess. We’re always following up to tidy up.

A lot of people think of gravediggers as a lonely bunch of guys too. In literature, often a character couldn’t get another job and ended up as a gravedigger. A lot of skills are involved though – you have to be up to date on health and safety, risk assessments and digital skills.

I think it’s still got an old-fashioned image, a top hat and red neckerchief – slightly spooky. But I’ve subscribed to a paranormal magazine for years and I’ve read more in there than I’ve ever seen here.

Cemetery life is a bit ordinary. People may think I’m pushing my way through spirits, but it’s nothing like that.

The sexton in literature

“It by no means follows that because a man is a sexton, and constantly surrounded by the emblems of mortality, therefore he should be a morose and melancholy man; your undertakers are the merriest fellows in the world”.

The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton, by Charles Dickens.

How has the role changed during the pandemic?

I don’t think people realise how much went into preparing for the pandemic. We had a month to get everything ready for whatever happened and get a spare mortuary up and running.

There was a massive amount of logistics we never thought we’d have to deal with. You can’t dig a slit trench and put 20 people in there. We’ve got to spread things out and make sure nobody thinks: “My god, there’s been 15 deaths overnight”.

We had Zoom calls every Monday, where we were being told about latest problems. We were dealing with contagion, social distancing at funerals.

It was a machine that was unstoppable once it went, and it’s only just slowing down now.

What keeps you going at work?

I suppose, in a way, [knowing] that the problems that come up are not going to last.

A lot of issues are a knee-jerk reaction, venting. Grief is a terrible thing to see day-by-day. You don’t see that person in their usual frame of mind. People write inscriptions on headstones and then six months later, they wish they’d never gushed like that.

You do get used to it. You talk to someone [who is grieving] and they slowly but surely come round. There are actually courses on grief that we do go on, but it’s not the be-all-and-end-all of it.

There are also quite funny things you come across, unusual things. One woman left a note saying: “Oh for god’s sake, don’t bury me anywhere near my husband.”

And I did one [burial] once of a young disabled woman. About four years before that, we had buried a teacher from the nearby school in the next plot along. The family asked me if this was intentional, and I didn’t know what they meant.

We had actually buried their daughter next to her teacher. A person who cared for her in her life, and in some people’s minds would be caring for her afterwards. Certain coincidences like that happen that are very strange, that point towards the supernatural.

What are you most proud of in your career?

The thing I’m most proud of though is the fact I have stuck it out, to tell the truth.

You travel through life and you have your own problems. I have six kids, we’ve had all manner of things occur. But you get up and you come in once every day, for 43 years.

I’m most proud of my long service and the fact I’ve worked with people who’ve appreciated it. I’ve had awards over time for long service and I feel valued here.