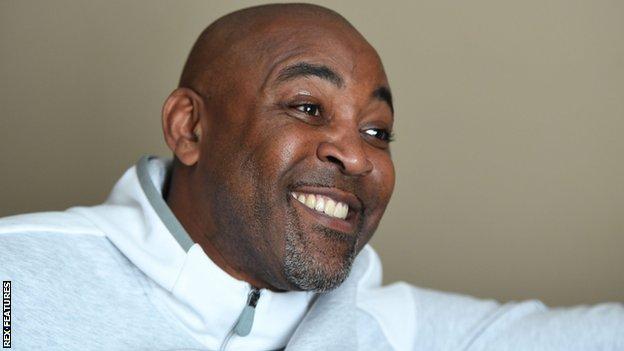

To a generation of athletics fans, Darren Campbell was the face of British sprinting.

His 200m silver at the 2000 Olympics and 4x100m gold four years later earned him widespread respect and fame.

Yet for years the source behind his inner drive remained hidden from public knowledge.

This is the story of how Campbell emerged as a talented teenage sprinter while leading a double life as a gang member; how a twist of fate foiled a planned pub robbery, how he survived a city-centre knife fight and why he eventually fled Manchester following the murder of a family friend.

Campbell, now 47, rarely spoke during his career about his experiences growing up on the Racecourse estate in Sale – a council estate on the outskirts of south Manchester.

As he prepares to guide the current crop of British youngsters through the Tokyo Games as Team GB sprint coach, he has decided to lay it all out there – “the good, the bad and the ugly” – in a bid to inspire others.

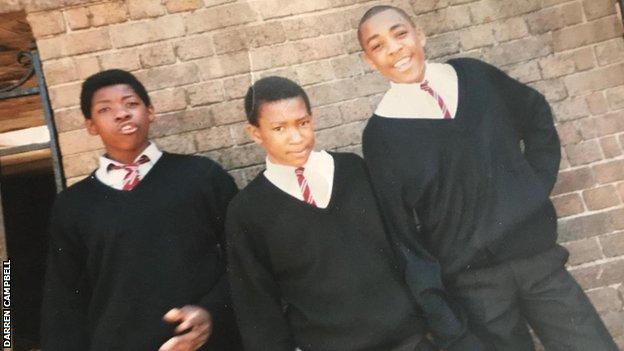

Campbell and his younger sister Sophia were raised by their mother, Marva, in a two-bedroom flat on Sale’s Racecourse estate.

He met his father for the first time, aged 13, at a sports awards ceremony. That was when he decided to drop his paternal surname – Grant – in favour of his mother’s, Campbell.

“I told my mum: one day I’m going to be famous and I don’t want my dad to take the praise,” Campbell says. “If he tries to take credit for it, he’ll have to explain to the world why we’ve got different names.”

Born in 1973, Campbell had already told anyone who’d listen that he’d one day compete at the Olympics. He’d been inspired by Carl Lewis’ performances at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, where the American sprinter won gold in the 100m, 200m, long jump and 4x100m.

By that time, the budding young athlete had already been competing for Sale Harriers for four years, enrolled after his mother was bowled over by his first school sports day.

Campbell’s mother was a constant source of strength and inspiration to her son. She was a strict parent – Campbell describes her as “the most feared on the estate” – but the fact she often worked two or three jobs meant he also spent plenty of time with his extended group of friends, for whom trouble was never far away.

“Initially it was a brotherhood, a group,” he says. “Unfortunately, as time went on it became more of a gang. An ‘us against the world’ kind of thing, because that is how you found yourself.

“I wouldn’t say we were bad kids because we weren’t. But as we got older it was easy to get dragged into the different things on the estate. You became a product of your environment. The things you see are gangs, gun crime, knife crime, drugs.

“There was lots of fighting. That means you’ve got to learn to protect yourself and your friends as well. It was down to that – protecting each other – that we became a gang. Then things escalated from there.”

While Campbell’s life was taking a sinister turn, his athletics was blossoming.

Success for youth teams at Sale Harriers was followed by school honours at regional and then national level. Yet, at age 16, Campbell’s Olympic dream seemed a world away. His more immediate concern was how to put some money in his pocket, which is why he agreed to take part in a pub robbery.

“As a group we’d sat down and thought about how we could create a bit of quick money,” he says.

“Somebody came up with the idea about a pub, not on the estate, that we could go to after closing time and rob that night’s takings. For me it sounded like a crazy plan, and when I was riding my bike on the way there I kind of looked up to the heavens and said ‘show me a sign’.

“Soon after that my bike got a puncture. It meant that, because I was the one who was supposed to ride back with the money as I was the fastest, we felt like we couldn’t go ahead with it.

“I have always seen that as a ‘sliding doors’ moment and I’ve always felt fortunate that it didn’t happen. My life would have been totally different. Overcoming the fear of doing it the first time would have made doing it the second, third and fourth time a lot easier.

“It would have just been a spiral, that’s how I view it.”

At the time, though, Campbell still struggled to see a way out.

Members of his inner circle were starting to form allegiances with other more serious gangs in Moss Side, which brought unwanted attention and an ever-increasing threat of violence.

“It was like I was living in two different worlds,” he says. “I had this athletics world, then I had this other world with my friends, with people who I’d grown up with. They protected me and I protected them.

“I did feel as if I had a lot more to lose but I was naive to the risks I was taking with my future. I certainly wasn’t looking at my life thinking in two years’ time you’re going to be representing your country.”

Sport was becoming serious, but so was his gang.

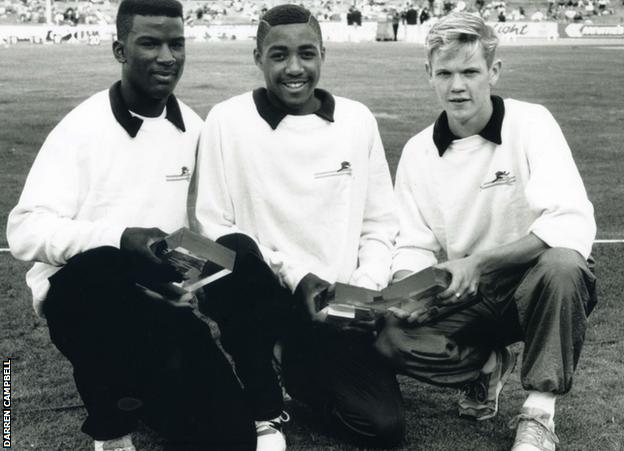

In the summer of 1991, aged 17, he won 100m and 200m gold at the European Junior Championships in Thessaloniki, Greece. On his return, he escaped an attempted stabbing during a brawl at Manchester’s Arndale Centre.

“A gang of guys spotted me and my friend in the shops,” he says. “My friend had beaten up one of their friends and they decided to go for us.

“A knife was brought out. The person with the knife tried to stab me. I managed to get out of my coat, so the knife slashed my coat.

“Luckily we were able to escape. Being part of a gang and creating those battle lines meant at any moment you could find yourself in a situation where you could end up losing your life.”

If the knife fight served as a shocking reminder of the tightrope Campbell was walking, the murder of his mother’s godson and fellow gang member ‘T’ – shot dead as part of another feud – came as a devastating blow.

“T was part of the gang that was based in Moss Side,” Campbell says.

“He didn’t live on the estate where I grew up. He was up to different stuff and got himself into a situation where there’d been an altercation with another group and they basically got somebody to assassinate him. That’s the reality of it. To this day we still don’t know who killed him.

“It was difficult. It showed me how fragile life could be and how quickly somebody could be taken away. It led me to a situation where I had a choice to make – whether to stay in Manchester or not – because my mum had heard I was on a hitlist.

“When she asked me to leave Manchester, I just knew I had to go.”

The offers came in. Following further success at the 1992 World Junior Championships in Seoul, South Korea, where he won silver in the 100m and 200m as well as gold in the 4x100m relay, Campbell was in demand. He eventually decided to go and train with Colin Jackson’s coach, Malcolm Arnold, in Newport, south Wales.

Campbell initially lodged with Arnold’s family as he made the transition from junior track star to full-time athlete. But while he looks back on those times fondly with a mentor he describes as “the best coach in the world”, the young Mancunian did not immediately take to a life in athletics.

Disenchanted by the impact he felt drugs had at the top level of the sport, he decided to walk away and instead targeted a move into football.

Spells at Plymouth Argyle and non-league Weymouth followed before the realisation dawned that if he was going to make it in any sport, it would be athletics.

Campbell returned to full-time training in south Wales in 1995 alongside Linford Christie, Colin Jackson, Jamie Baulch and Paul Gray. He went on to finish fourth in the 100m at the British Championships the following year and was picked as part of the 4x100m relay team for the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.

There was to be no fairytale introduction to the Games for Campbell as he dropped the baton in the semi-finals of the relay, but results slowly improved. A 100m silver medal in the British Championships of 1997 was followed by relay bronze at the World Championships the same year.

He then made his big breakthrough in 1998 with national and European titles in the 100m, along with relay gold at the European Championships and Commonwealth Games.

Campbell’s life was finally set on the right course. That same year he met his wife Clair, with whom he now has three children, and Newport is still their home today.

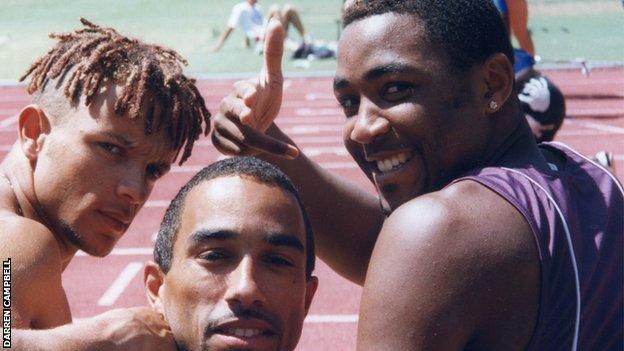

But he has never forgotten his roots, staying in close contact throughout his life with childhood friends and former gang members Lynx and Marlon. And he believes the battling qualities he relied upon in his youth played an integral part in the success that was to come on the senior international stage.

Campbell realised his lifelong dream of racing in the 100m Olympic final in Sydney in 2000, finishing sixth. He took a silver medal from the 200m at those Games, and four years later in Athens came gold in the 4x100m relay.

By the time of his retirement in 2006, he’d also won two bronze medals and one silver in the World Championships, three gold and a silver at European Championship level and two gold and one bronze at the Commonwealths.

For any athlete, it’s difficult to top the experience of winning Olympic gold. For Campbell, the moment carried an extra power.

“When I won Olympic gold, the reason why I wasn’t in the huddle celebrating with the rest of the team was because I was literally in floods of tears,” Campbell says.

“It was like I was having flashbacks of my whole life – the good, the bad and the ugly.

“It all just came flooding back, along with the appreciation of how fortunate I was to have made it through and to have achieved my dreams.

“Those tears were not just for me. They (his old friends) have been there with me throughout. My success is their success. That’s how I view it and that’s why I’m so grateful they got through life the way I got through.

“They may not have had the success I have had as an athlete, but I see them as being successful as people because I know how difficult their start in life was.

“I know we’ve been fortunate to have got through it and still be here.”

It’s why Campbell has decided to write his autobiography, Track Record.

“I feel it’s important not to hide away from where I have come from, just to show that anything in life is possible.

“In life it’s not about where you start, it’s about where you finish.”