By Dearbail Jordan and Faisal Islam, Business reporter and Economics editor

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Bank of England has opened the door to cutting interest rates in August in what would be the first drop in borrowing costs for more than four years.

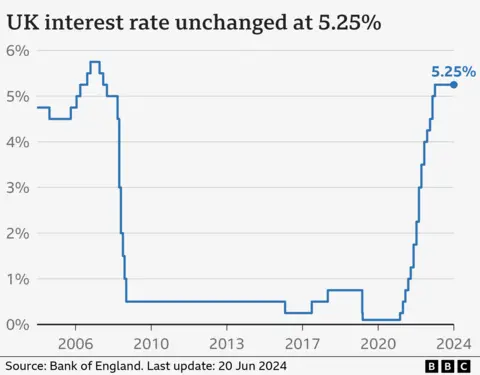

On Thursday, the Bank voted to keep interest rates at a 16-year high of 5.25% in a close-run decision.

Earlier this week, figures revealed that inflation – which measures the pace of price rises – had slowed to 2% in May, which is in line with the Bank of England’s target. However, prices of some items continued to rise faster than expected.

But the minutes from the Bank’s rate-setting committee signalled a significant change in tone, indicating a majority could vote for a cut when they meet again on 1 August.

They say they will look at whether areas of concern are “receding”.

“On that basis, the committee will keep under review for how long [the] bank rate should be maintained at its current level,” the minutes said.

While not a done deal, this language is a clear signal to the markets and the public that after the Bank completes its new forecasts for the economy, a rate cut is now the most likely outcome at its next meeting.

The rate-setting committee voted 7-2 to hold rates, but the result was not as cut and dried as it had been previously. For three members, voting to hold this month was a “finely balanced” decision.

Those committee members leaning towards a cut, which are understood to include Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey, are playing down the strength of underlying inflationary pressures.

The Bank’s latest decision comes in the run-up to the general election, with policies for the future of the UK economy a key battleground for political parties.

However, the Bank stressed that the timing of the election was “not relevant to its decision”.

The Bank of England’s interest rate has a knock-on effect on mortgage, credit card and savings rates for millions of people across the UK.

While the Bank appears to be hinting at a cut in August, many homeowners now coming to the end of a fixed-rate deal are facing mortgage rates much higher than they have become used to.

The current average rate for a two-year fixed deal is 5.96%, although this is lower than last year’s peak of 6.86%.

People in tears over mortgage costs

Ben Perks

Ben PerksMortgage adviser Ben Perks, who works in Wolverhampton, told BBC Radio 5Live that while he was not surprised by the Bank’s decision to hold rates for now, he was “definitely disappointed, certainly frustrated”.

“It’s OK saying, ‘Oh, we’ll wait’ but the reality is that 125,000 people a month are coming to the end of their fixed rates, which over a two-month period is the population of Wolverhampton city centre.”

He says he’s had borrowers in tears in his office when they’ve found out how much their mortgage repayments are going to go up by.

“It is extremely stressful. We’ve had meetings when you tell them the new payments and, with the fact everything else has gone up, they don’t know which way to turn.”

Wednesday’s inflation data showed that price rises for services – which reflect the cost of items such as cinema tickets, restaurant meals and holidays – remained higher than expected.

But the Bank’s minutes say that the slow fall in services inflation reflects one-off factors, including the rise in the minimum wage and bills that automatically rise by inflation, such as broadband and mobile.

If the Bank does go ahead with an interest rate cut in August, it would be the first one since March 2020 when the UK was heading into the first Covid lockdown.

“It’s good news that inflation has returned to our 2% target,” said Bank governor Andrew Bailey.

“We need to be sure that inflation will stay low and that’s why we’ve decided to hold rates at 5.25% for now.”

The Bank of England is independent of the government and its main role is to keep inflation stable at 2%.

In response to high inflation, the Bank in recent years has raised and then kept interest rates at a high level.

The theory behind rising rates is that it will slow inflation, but it can also drag on economic growth as businesses may put off investment or hiring, which could mean fewer jobs being created.