It was a story that football will never forget.

The crisis sparked by the European Super League (ESL) and its subsequent collapse remained towards the top of major TV and radio bulletins, and on newspaper front pages throughout the week.

Outside of major events like an Olympics or World Cup, very few sports news stories have dominated headlines, nor generated such interest. The great Fifa corruption scandal of 2015 is the only one I can recall that came close in terms of impact and intensity.

Certainly the events of Tuesday when – while furious fans protested outside Stamford Bridge and those close to the ESL insisted the project was proceeding as planned – I learned that Chelsea were preparing to pull out, sparking the implosion of the entire project on a seismic evening of chaos and climb-downs, were as dramatic as anything seen on the pitch this season.

But, while the despised breakaway may have unravelled, and the level of mainstream interest has now faded a little, the story is far from over.

Not with the unprecedented backlash it generated across the game and beyond, and what it told us about the importance of our national sport and its traditions in our lives and society.

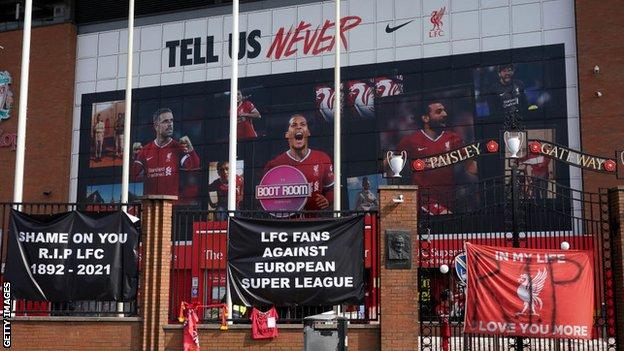

Not with the influence that fans suddenly seemed to wield, along with the willingness of players to voice their dissent, even if it means breaking ranks with those that employ them.

Not with a fan-led review into the sport being ordered by the government.

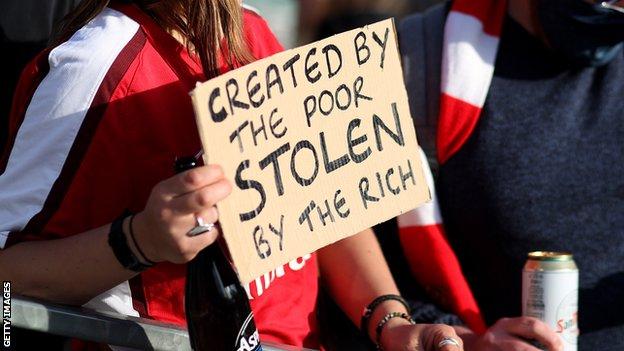

Not with the protests against the schemers’ perceived greed and secrecy continuing.

Not with Real Madrid supremo and ESL chairman Florentino Perez still insisting the plan is merely “on standby”, rather than abandoned altogether, and that the clubs involved cannot escape from binding contracts.

And not with the desire for real change that this remarkable episode has left as a legacy.

The conditions that led us here remain.

The billionaire overseas owners that have been welcomed into the English game over the past two decades by football authorities and politicians alike, some of whom backed the plan in the pursuit of greater revenue, and who in some cases have not been seen at the clubs they own for literally years, remain in place.

The American owners of Manchester United, Liverpool and Arsenal in particular – who unlike those from Russia at Chelsea and Abu Dhabi at Manchester City – are seen to prioritise revenue rather than reputation, may now reconsider their long term commitment to the clubs they own.

But even if they now decide to sell, as many fans hope, the number of potential buyers with the wealth or interest to purchase such clubs are, of course, limited.

Until such clubs are put up for sale, regardless of the grovelling apologies their owners have issued in recent days, their desire to grow their businesses and attract new audiences, especially after the unprecedented financial crisis of the past year, will continue.

The value of broadcast rights do seem to have peaked. A lack of domestic competition in Italy and Spain seems unlikely to end. Nor is the hundreds of millions of pounds worth of debt several of the continent’s wealthiest clubs – especially Real Madrid, Barcelona and Juventus – are saddled with.

The huge financial inequality in the English game, between the Premier League and the EFL, continues. Very few seem to be arguing that sticking with the status quo is an option.

So what next?

Based on conversations in the past 48 hours, my belief is that those demanding that the English clubs involved in the plot are punished with points deductions or bans are set to be disappointed.

The mood music from within the FA and Premier League is that such moves would unfairly punish the fans. The very supporters whose protests and opposition seemed to prove decisive in bringing down the ESL.

That is not to say disciplinary action will not be taken against the individuals involved, nor that their clubs will not suffer as a result of the conspiracy. Indeed, they are already paying the price. Executives from the ‘Big Six’ who sit on influential Premier League working groups have been told to stand down, or be voted out.

And it will not stop there. Clearly there is an appetite from within the 14 clubs excluded from the plot – and the FA – to toughen up their rules to try prevent any such repeat in the future.

Within the Premier League this is being seen as a historic opportunity to clip the wings of the wealthiest clubs, and to put an end to the hopes they clearly had for more power, as shown last year when it emerged they had been holding secret talks over a different scheme – Project Big Picture.

For years the wealthiest clubs had used the threat of a breakaway as a negotiating tactic to secure concessions. In 2018 for instance when they secured a greater share of the overseas broadcast revenue generated by the Premier League. And more recently when they persuaded Uefa to create two ‘wild card’ slots for clubs who fall outside the qualification places but can still get in on the basis of past European success as part of the revamped Champions League format.

With the threat of a ‘super league’ apparently over (for now), some will hope an overhauled European Club Association will push for such concessions to be reversed.

Others want far greater redistribution of Champions League revenue – currently one of the biggest causes of financial disparity within the Premier League.

And the big clubs’ recent demand for control over the commercial rights for the competition should certainly now be over. Maybe the desperation of some of the bigger clubs to somehow claw back trust with their enraged supporters could even mean a reduction in ticket prices as a gesture of goodwill. And perhaps not.

There have been plenty of taskforces and reviews of football in the past. But coming as it does in the wake of arguably the greatest threat the sport’s pyramid has faced, the sense is that the one now being conducted by well-respected former Sports Minister Tracey Crouch has much more chance of bringing about real change than any before. And that given the recent flexing of ‘fan power’, those who represent supporters will be properly listened to.

While the government has said it wants her to look at the German model of ownership where fans have a majority stake, and many are in favour of it, the so-called ’50+1′ approach appears unlikely, certainly in the short-term in English football, where for the last two decades, billionaire overseas investors have been able to buy up so many clubs.

Some believe Crouch is more likely to recommend a strengthened Owners and Directors Test, greater fan representation and statutory roles on club boards, a ‘golden share’ system in which fans have a veto over key decisions, fans having the right to buy a certain proportion of a club, more independent board members at the FA, and perhaps even an independent and powerful football regulator, with the power to decide who clubs can be acquired and run by.

Such a role has been proposed by former FA chairman David Bernstein and pundit Gary Neville, and the football authorities will almost certainly oppose it. Just as the Premier League is expected to oppose the greater sharing of its broadcast revenue that the EFL continues to demand.

The view within the game is that a change to the law will also now be required.

The interim ruling of a Spanish court earlier in the week appeared to prevent football’s authorities from using sanctions such as expulsion to block the breakaway on the basis such punishments would have contravened competition law. It therefore highlighted a serious weakness in football’s ability to enforce its rules. Those at the heart of the crisis seem to agree that ultimately the ESL would have prevailed in the courts, or at the very least succeeded in dragging the dispute out over months, if not years, by which time the ESL would have been established.

The government’s promise this week to legislate, effectively in order to grant football an exemption from competition law, along with the support of the opposition parties – was deemed crucial in defeating the ESL plotters. Well-placed sources within the Premier League believe this was a crucial miscalculation by the ringleaders of the plot, who assumed politicians would not want to get too involved.

Perhaps in Spain and Italy such an assumption was fair. But in England it proved drastically misguided. For now, the threat of a breakaway has retreated, but expect such legislation to follow as a means of empowering football’s authorities.

Many will now hope that the same passion, unity and player activism that the ESL provoked can be applied to other issues in the game; from racism and social media abuse to concerns over human rights.

Because tempting as it may be to assume all is well with the sport now that the ESL has been vanquished, the reality is of course somewhat more complicated.

Be wary of the potential for hypocrisy at this time. Fifa may claim to have been on the right side of history this week, but they have also presided over an era in which the 2022 World Cup was awarded to Qatar, arguably the most controversial host of a major sports event in any decade.

Fifa’s President Gianni Infantino is no stranger himself to controversial new competitions and formats, proposing a lucrative new Nations League and Club World Cup, before the plans were put on hold amid another Uefa backlash.

Uefa may have been viewed as the victor this week, but remember that many clubs fear that its new, enlarged Champions League, with yet more matches, will threaten player welfare in the pursuit of more money. And as both Shaka Hislop and Andros Townsend said this week, many will wish the federation showed as much dynamism and ruthlessness against racism as it displayed this week against the ESL, when its power and wealth seemed threatened.

The Premier League and the FA may have condemned the insurgency, but do not forget that the top flight was created with a breakaway in 1992. Yes, promotion and relegation was retained of course, and there have been undoubted benefits. But many believe that many of the financial issues the English game now wrestles with lower down the leagues, can be traced back to that moment.

It was only a few months ago that the Premier League sparked outrage by announcing plans to show matches on pay-per-view TV, reinforcing the feeling many have that traditional fans have been gradually priced out of the game over the past 30 years. The idea was shelved, but not before the league was accused of greed.

Politicians may have been quick to condemn the clubs behind the breakaway this week. But many seemed happy enough in recent years for most of the country’s top clubs to fall into the hands of the overseas-based billionaires who took the game to the brink this week.

Indeed, there seemed little objection from politicians to the possibility of Newcastle United being taken over by a Saudi-backed consortium last year before the deal collapsed. Some may ask why it has taken until now for a realisation there may need to be more regulation when it comes to ownership.

The seismic but ultimately farcical attempt to launch a super league will be remembered as a pivotal moment in the sport’s history. The moment when many in football, having seen the wealthiest clubs consolidate more power and wealth over years, finally said ‘enough’ and fought back. But the game is not yet over, and future battles lie ahead.