“Significant institutional failings” by the Football Association meant it “did not do enough to keep children safe” – according to the findings of an independent review into historical child sexual abuse in the game.

It found the FA was “too slow” to have sufficient protection measures in place between October 1995 and May 2000.

It said there was no evidence the FA knew of a problem before summer 1995.

The report focused on the abuse of children between 1970 and 2005.

It said: “The FA acted far too slowly to introduce appropriate and sufficient child protection measures, and to ensure that safeguarding was taken sufficiently seriously by those involved in the game. These are significant institutional failings for which there is no excuse.”

In a statement, FA chief executive Mark Bullingham offered “a heartfelt apology” from the English game’s governing body to all survivors and added there was “no excuse” for its failings.

“No child should ever have experienced the abuse you did,” he continued in an address to those affected.

“What you went through was horrific and it is deeply upsetting that more was not done by the game at the time, to give you the protection you deserved.”

The long-awaited 710-page review, led by Clive Sheldon QC and commissioned by the FA in 2016, found:

- Following high-profile convictions of child sexual abusers from the summer of 1995 until May 2000, the FA “could and should have done more to keep children safe”.

- There was a significant delay by the FA in putting in place sufficient child protection measures in football at that time. In that period, the FA “did not do enough” to keep children safe and “child protection was not regarded as an urgent priority”.

- Even after May 2000, when the FA launched a comprehensive child protection policy and programme, “mistakes were still made” by the FA.

- The FA failed to ban two of the most notorious perpetrators of child sexual abuse, Barry Bennell and Bob Higgins, from involvement in football.

- There were known to be at least 240 suspects and 692 survivors, yet relatively few people reported abuse and the actual level was likely to be far higher.

- Where incidents of abuse were reported to people in authority at football clubs, their responses were “rarely competent or appropriate”.

- Abuse within football was “not commonplace”. The overwhelming majority of young people were able to engage in football safely.

- While several of the perpetrators knew each other, there was not evidence of a “paedophile ring” in football – Sheldon says: “I do not consider that perpetrators shared boys with one another for sexual purposes, or shared information with one another that would have facilitated child sexual abuse.”

Sheldon, whose review made 13 safeguarding recommendations, said: “Understanding and acknowledging the appalling abuse suffered by young players in the period covered by the review is important for its own sake.

“Survivors deserve to be listened to, and their suffering deserves to be properly recognised. As well as recognising and facing up to what happened in the past, it is also important that this terrible history is not repeated, and that everything possible is done now to safeguard the current and future generations of young players.”

Bullingham said the report was “a very important piece of work” made possible by “survivors bravely” coming forward.

He added that “today is a dark day for the beautiful game” and a “critical moment” for English football, which he admitted had been “too slow to act”.

“We must acknowledge the mistakes of the past and ensure that we do everything possible to prevent them being repeated,” he continued.

“Thankfully there have been huge strides in safeguarding in sport and football over the past two decades, and the report recognises that English football is in a very different place today.”

How did this start?

On 16 November 2016, former footballer Andy Woodward waived his right to anonymity to talk about how he was sexually abused by Bennell at Crewe Alexandra from the age of 11 to 15.

Several other people contacted police in the following days, before former England and Tottenham player Paul Stewart said he was abused as a child by a coach, later named as Frank Roper.

Children’s charity the NSPCC set up a hotline with the FA, dedicated to footballers who had experienced sexual abuse – more than 860 calls were received in the first week.

After investigations involving several police forces started, the FA announced an independent inquiry into non-recent child sex abuse, led by Sheldon.

The independent review made its first call for evidence in January 2017, writing to all football clubs in England and Wales, amateur and professional, asking for information about allegations between 1970 and 2005.

Sheldon’s review said the FA was not aware that abuse had actually occurred in football prior to the summer of 1995, before Bennell had been convicted in Florida in connection with a football-related tour.

The report found the provision of child protection guidance was “not something which was happening widely within sport”.

Who are the offenders?

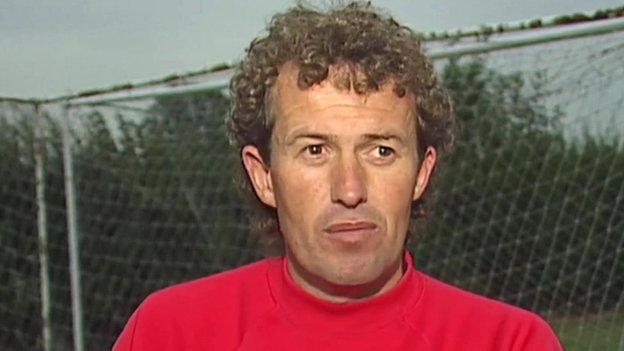

Barry Bennell – the former Crewe Alexandra and Manchester City coach is serving a 34-year sentence after being convicted of child sexual abuse five times.

He has been convicted of sexual abuse against 22 boys in total, although it is believed more than 100 victims have come forward to say they were abused by Bennell.

George Ormond – the former Newcastle youth coach was jailed in 2002 for six years after being found guilty of abusing seven boys under 16 between 1975 and 1999.

Other victims subsequently came forward and Ormond was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2018 after being found guilty of 36 counts of sexual abuse against 18 victims between 1973 and 1998.

Eddie Heath – Chelsea announced in November 2016 they were investigating allegations of sexual abuse by former chief scout Heath, who died in 1983.

Evidence from 23 witnesses detailed how Heath groomed and abused young boys aged 10 to 17 in the 1970s. An external review said some adults at Chelsea must have been aware of Heath’s abuse but “turned a blind eye”. Chelsea apologised unreservedly after the review was published in 2019.

Bob Higgins – the former Southampton and Peterborough youth coach was jailed for 24 years and three months in 2019 on 45 counts of indecent assault against 24 boys.

Higgins went on trial in the early 1990s but was acquitted. Multiple former players came forward with allegations of abuse by Higgins in 2016 and 2017.

Michael ‘Kit’ Carson – the 75-year-old killed himself by crashing into a tree on the first day of his trial in 2019. He was accused of sexually abusing boys under 16, from 1978 to 2009. Carson had worked for Peterborough United, Cambridge United and Norwich City.

Ted Langford – the former Aston Villa and Leicester City part-time scout was jailed in 2007 for the sexual abuse of four boys between 1976 and 1989.

Frank Roper – worked as a scout in the north west of England. Roper, who died in 2005, sexually abused young footballers while recruiting players to Blackpool’s school of excellence.

Phil Edwards – former Watford physio who died in 2019 while on bail for an alleged child sex offence. Hertfordshire police were subsequently contacted by 16 people who made complaints about Edwards.

Some of the former players affected

Andy Woodward – was abused by Bennell as a junior Crewe player from the ages of 11 to 15. He told the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire programme the abuse had a “catastrophic” impact on his life.

Chris Unsworth – the ex-Manchester City youth player was abused by Bennell from the age of nine. Unsworth told the BBC he had been “raped between 50 and 100 times”.

Steve Walters – was abused by Bennell and said it began at the age of 12 when he would stay at the former coach’s house in the town during the school holidays. He told the BBC the abuse was “absolutely petrifying”.

Paul Stewart – the former Manchester City, Tottenham and Liverpool player was abused by Roper daily for four years up to the age of 15.

“He was threatening that he would kill my parents and my two brothers if I ever spoke out. I was just absolutely frightened,” Stewart told the BBC.

Paul Collins – played briefly for Charlton Athletic and was groomed by Heath with free boots and holidays. The trauma Collins suffered led to him quitting the game early in his career. Watch the interview here.

Gary Johnson – the ex-Chelsea player joined the club as an 11-year-old in 1970 and said he had been groomed by Heath from the age of 13. He said the club paid him a £50,000 settlement that included a confidentiality clause.

David Eatock – the former Newcastle United player told the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire show he had been groomed by Ormond from the ages of 18 to 21. He said he “froze” with fear during an assault in Ormond’s van.

Tony Brien – said he was abused by Langford from the age of 12 when he was playing for a local youth team Dunlop Terriers in the early 1980s – a feeder team for Leicester and Aston Villa.

Former Villa manager Graham Taylor is alleged to have discouraged Brien from going public with his allegations. Taylor died in January 2017.

What about the individual football clubs?

The report said that for much of the period the review covered:

- club staff and officials were generally unaware of child protection issues;

- they were not trained in child protection issues;

- they did not identify or respond to signs of potential abuse;

- and if they were aware of the signs, they did not examine them with curiosity or suspicion.

In March 2019, Manchester City set up a multi-million pound compensation scheme for victims of historical child sexual abuse carried out by former coaches.

The report said that City senior management were aware of rumours and concerns about Bennell’s conduct in the early 1980s.

It added: “The club did not investigate these rumours. It should have done so. The club should also have investigated the arrangements for boys staying at Bennell’s house.”

City commissioned an independent review in November 2016, led by Jane Mulcahy QC, that was also published on Wednesday.

In addition to personal apologies made by the club to survivors, City said its board of directors wished to “apologise publicly and unreservedly for the unimaginable suffering experienced by those who were abused as a result of the club’s association” with Bennell and two other convicted abusers, John Broome and Bill Toner.

It added: “The club also extends its heartfelt regret and sympathy to the multiple family members and friends affected by these traumatic events, the ramifications of which are felt by so many to the present day and will continue to be felt for a long time to come.”

Crewe Alexandra have reiterated they were not aware of any sexual abuse by Bennell until 1994 when he was convicted of sexual assault, and did not receive a single complaint about sexual abuse by him.

The Sheldon report said: “It is likely that three directors of Crewe Alexandra FC discussed concerns about Bennell which hinted at his sexual interest in children.

“There is no evidence that the advice of a senior police officer to the club’s former chairman to keep a ‘watching brief’ on Bennell was heeded.

“The club should also have ensured that there were appropriate arrangements in place for boys staying overnight at Bennell’s house.

“The boys should have been spoken to periodically to check that they were being properly cared for. Had such steps been taken, this might have led to boys making disclosures to the club.”

Sheldon said former Crewe manager Dario Gradi “should have done more” to investigate concerns about Bennell but was not involved in a cover up.

Gradi, who has always denied any wrongdoing, is also criticised in the report for not doing more when a claim of abuse by Heath was reported to him while assistant manager at Chelsea in 1975.

The report states that Gradi “did not consider a person putting their hands down another’s trousers to be an assault”, but that he changed his mind after Sheldon insisted it was.

Gradi, 79, was suspended in 2016 pending an FA investigation and retired from his position of director of football at Crewe three years later.

Bullingham said on Wednesday that Gradi was “effectively banned for life” from football but could not go into the reasons.

The FA’s director of legal and governance Polly Handford said it was “for safeguarding reasons” but that was “as far as we can go”.

Stoke City were “also aware of rumours about Bennell” during his time associated with the club in the early 1990s, said the report, and steps should have been taken to monitor his activities.

Premier League clubs Aston Villa and Leicester paid damages to five victims of Langford in March 2020. The report said Aston Villa should have reported disclosures about sexual abuse by Langford to the police when his role as a scout was terminated in July 1989.

And on Wednesday, Southampton admitted “considerable failings” and said they were “deeply sorry” to young footballers abused by Higgins.

The report found Southampton and Peterborough United FC were also aware of rumours about the inappropriate behaviour of Higgins, and were aware that boys were staying at his home.

“This awareness should have resulted in greater monitoring by the clubs. Had Higgins been properly monitored this might have prevented some of his abuse of young players,” the report added.

At Chelsea, in relation to Heath, the Sheldon report said steps should have been taken to protect the young player who had made a disclosure about abuse in or around 1975.

Newcastle United should have acted more quickly following disclosures of abuse by Ormond at the youth club Monty’s in early 1997.

Ormond was only removed from the club many months later, and after he had been permitted to travel abroad with young players.

The report found that despite being aware of the allegations, no additional safeguards were put in place by the club.

In a statement, Newcastle expressed their “sincere apologies and sympathy to all individuals affected by historic abuse in football and commend the bravery of those who have come forward and shared their stories”.

The club added that they now have “comprehensive and robust safeguarding measures in place to protect and support young people throughout the football club”.

What are the review recommendations?

Among Sheldon’s recommendations are the introduction of safeguarding training at several levels in the game, including all players and young people as well as the FA board and senior management team.

He also recommends there should be safeguarding officers employed by all Premier League and English Football League (EFL) clubs.

Both league governing bodies say they and associated clubs have safeguarding leads at board level, as well as dedicated safeguarding staff.

The Premier League said it accepted the report’s “findings and insight it provides”, and added the recommendations “will further strengthen safeguarding arrangements across the game” as “there is no room for complacency”.

The EFL also said it accepted the advice and would work with the FA, clubs and other stakeholders “to ensure [the recommendations] are implemented as a minimum [standard], where they have not been already”.

Both the Premier League and EFL said they were “well placed to meet all the recommendations” and that the findings would inform a review of safeguarding governance, support and awareness arrangements.

The Offside Trust, the organisation set up by survivors of child sexual abuse in sport, said the recommendations were “blindingly obvious to anyone” after the scandal broke in 2016.

It added it was “disappointed not to see anything stronger in terms of mandatory reporting” and it would have liked to have “seen more on wealthy clubs supporting grassroots safeguarding”.

Reaction to the Sheldon report

Julian Knight MP, chair of the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport committee, said: “The failure of the FA to keep children safe is truly shocking.

“There can be no excuses for the critical delays to act or provide guidance to those working on child protection. We could be looking at the biggest safeguarding scandal in football’s history.”

Former Manchester City junior player Gary Cliffe was among the survivors of Bennell’s abuse. He said the ex-coach abused him hundreds of times between the ages of 11 and 15.

Cliffe told BBC Sport this was an “absolutely monumental day” because of of the publication of the findings.

“It matters so much because it’s impacted on my life and numerous other people’s lives,” he added. “We are hoping and looking for answers and culpability within that report.”

But Cliffe said he was disappointed with the suggestions in the report that suspicions of abuse were not acted upon.

“I don’t think he’s gone far enough,” he said.

“Throughout the whole report that I’ve read, there’s a theme that people knew or suspected, but none of the officials had the gumption to raise it with anyone – police, social services – anyone at all.

“It’s a theme running through it, so it’s disappointing from that respect.”

Ian Ackley was a youth player when he was abused and raped by Bennell over a four-year period.

Now working as an abuse survivor support advocate for the Professional Footballers’ Association, he said it would be “naive” to believe abuse had been eradicated.

“Make sure your children are safe,” he said. “Don’t assume that just because someone has got a badge, whistle or tracksuit that they’re OK to leave your children with.”

Former England international Paul Stewart, who was abused by Roper, told BBC News that there were “suspicions and rumours” of abuse, but they were “totally ignored”.

“It caused a lot of survivors a lot of damage as we got on through adult life,” he added. “I don’t think the report has shown how damaging the effects of abuse have been to individuals.

“We have to make sure we don’t get complacent and the abuse doesn’t happen again.”

- Football’s Darkest Secrets – a three-part series examining historic child abuse in youth football all across England between the 1970s and the 1990s, airs on BBC One, from Monday, 22 March.

If you’ve been affected by issues raised in this article, there is information and support available on BBC Action Line.