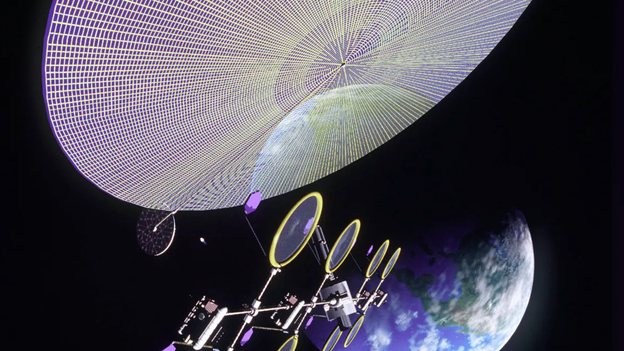

The possibilities don’t end there. While we are currently reliant on materials from Earth to build power stations, scientists are also considering using resources from space for manufacturing, such as materials found on the Moon.

But one of the major challenges ahead will be getting the power transmitted back to Earth. The plan is to convert electricity from the solar cells into energy waves and use electromagnetic fields to transfer them down to an antenna on the Earth’s surface. The antenna would then convert the waves back into electricity. Researchers led by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency have already developed designs and demonstrated an orbiter system which should be able to do this.

There is still a lot of work to be done in this field, but the aim is that solar power stations in space will become a reality in the coming decades. Researchers in China have designed a system called Omega, which they aim to have operational by 2050. This system should be capable of supplying 2GW of power into Earth’s grid at peak performance, which is a huge amount. To produce that much power with solar panels on Earth, you would need more than six million of them.

Smaller solar power satellites, like those designed to power lunar rovers, could be operational even sooner.

Across the globe, the scientific community is committing time and effort to the development of solar power stations in space. Our hope is that they could one day be a vital tool in our fight against climate change.

—

Amanda Jane Hughes is a lecturer in energy engineering at the University of Liverpool, where her research includes the design of solar cells and optical instruments. Stefania Soldini is a lecturer in aerospace engineering at the University of Liverpool, and her expertise includes numerical simulations for spacecraft mission design and guidance, navigation and control, asteroids and solar sail missions.

—

This article originally appeared on The Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons licence. This is also why this story does not have an estimate for its carbon emissions, as Future Planet stories usually do.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.