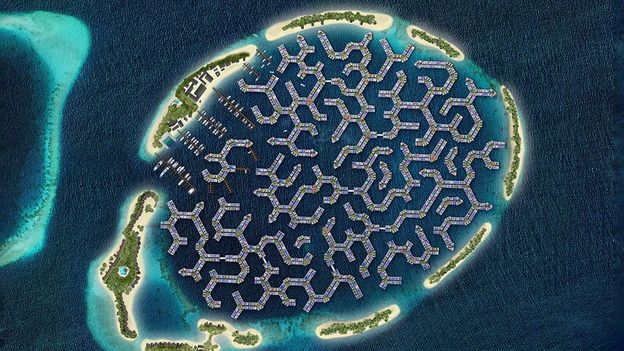

Other structures to protect the sea include constructing 18 groynes on the shores of the Eko Atlantic. A groyne is a structure built to trap sand and prevent it from washing into the ocean. Those installed at Eko Atlantic are each spaced 400m (1,300ft) apart and span a distance of 7.2km (4.5 miles). Further groynes have been proposed to cover up to 60km (37.3 miles) of the state’s coastline, with officials estimating this would cost $1bn (£800m), the News Agency of Nigeria reported.

Flood forecasting

While structural coastal defences might be some of the most visible interventions to counter flooding, one of the least visible could be at least as important for the city’s resilience.

Nigeria’s federal authorities have designed the Flood Mobile App to make predictions that could buy coastal regions the time to make adequate preparations to protect besieged cities like Lagos. The app is available online and provides real-time flood forecasting information about a specific location, using data collected by the Nigeria Hydrological Service Agency (NIHSA).

The app covers a much broader region than an earlier service, WetIn App, which was designed by Nigeria’s agriculture ministry. The WetIn App only targets farmers in three flood-prone states of the federation, giving warnings four days before an expected disaster. Prior to this, the authorities had to rely on media such as magazines, radio and television to get the word out about an imminent flood.

NIHSA is confident that the new Flood Mobile App will help people monitor daily flooding risks anywhere in Nigeria. Already, some early signals urging people to be on alert have started playing out, as torrential rains flood the roads in business and residential districts. Though smart device penetration remains relatively low among all but the younger population in cities, leaving out prospective users in the rural areas and those without mobile phones.

Without changes like these and many others, sea level rise this century would displace millions in Lagos, with low-lying districts like Makoko among the most vulnerable. But by learning to live on the sea and its waterways, defending the city’s coast and knowing when inundation is most likely, Africa’s largest city is leveraging its ingenuity to stay afloat.

—

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.