“I’m in favour of [targeted flooding] and think we on the Halligen should definitely support it,” says Katja Just, the mayor of Hooge, which is relatively rarely flooded because of its dyke. “But of course there are those who say, no, no, no way, that would lengthen land under, and then we can’t get away.” She believes, however, that the inconvenience is worth it, if it means preserving Hooge for future generations.

Even if they were eventually implemented on all the Halligen, the targeted floods will only be one element of a wide-reaching and costly plan to adapt the islands to climate change.

“If we want to hold on to the Halligen, there are several basic conditions,” says Hans-Ulrich Rösner, the director of the WWF’s Wadden Sea Office in the German town of Husum. “First, the mounds have to be raised, so people can live there. Second, the land has to grow, and that’s only possible through land under. Third, the edges have to be protected from erosion.” That last step has already been implemented for some decades, by fortifying the Halligen with stone edges. As a final point, Rösner emphasises that the surrounding Wadden Sea intertidal ecosystem also has to be preserved, because the Halligen ultimately can’t exist without it.

All these efforts, Rösner says, are going to be futile unless countries adhere to the Paris Agreement, an international treaty on climate change that aims to limit global warming: “Without well-functioning global climate protection, nothing can be saved here.”

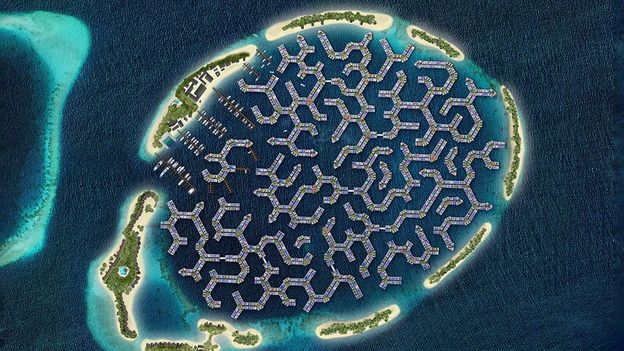

Climate mounds

The first of Rösner’s recommendations, raising the mounds, is already underway. The state of Schleswig-Holstein is aiming to gradually convert the mounds on the Halligen into so-called “Klimawarften”, or “climate mounds”, which will resist the rising sea. A climate mound is up to 1.5m (5ft) higher than conventional mounds, broad enough to accommodate future expansions, and has a long, gentle westward slope to take the heft out of the incoming floods, driven by west winds.

A pilot project to create three climate mounds on Hooge, Nordstrandischmoor and Langeness is nearing completion. It has turned out to be considerably more expensive than expected, costing between €3.7m (£3.2m/$4.5m) to €9m (£7.9m/$10.9m) per mound, largely because of the cost of the sand needed for construction, and its transport. Since no sand can be taken out of the protected Wadden Sea, it has to be brought in from elsewhere in the North Sea and on the mainland.