All this, experts say, underscores the need to track down and plug any leaks or sources that can be controlled. Tracing emissions to their source is no easy task, however. Releases are often intermittent and easy to miss. Ground-based sensors can detect leaks in local areas, but their coverage is limited. Airplane and drone surveys are time-intensive and costly, and air access is restricted over much of the world.

That’s where a sophisticated fleet of satellites – some recently launched, some soon to be deployed – comes in.

A cluster of satellites launched by national space agencies and private companies over the last five years have greatly sharpened our view of what methane is being leaked from where. In the next couple of years, new satellite projects are headed for launch – including Carbon Mapper, a public-private partnership in California, and MethaneSAT, a subsidiary of the Environmental Defense Fund – that will help fill in the picture with unprecedented range and detail. These efforts, experts say, will be crucial not just for spotting leaks but also developing regulations and guiding enforcement – both of which are sorely lacking.

“You can’t mitigate what you can’t measure,” says Cassandra Ely, director of MethaneSAT.

Earlier satellites, such as the Japan Aerospace Exploration’s Gosat launched in 2009, were able to detect methane, yet their resolution wasn’t good enough to identify specific sources.

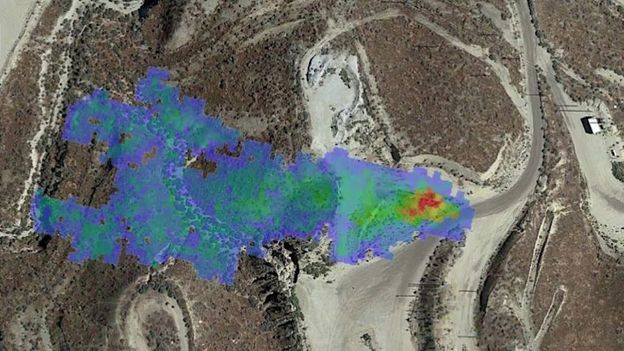

But satellite technology is now advancing rapidly, boosting sensor resolution, shrinking size, and gaining a host of cutting-edge capabilities. Powerful new eyes in space include the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 5P (launched in 2017), the Italian Space Agency’s Prisma (launched 2019), and systems operated by private Canadian company GHGSat (with satellites launched in 2016, 2020 and 2021). Companies like French Kayrros are using artificial intelligence to enhance satellite imaging, paired with air and ground data, to provide detailed methane reports.

In the past year, methane-hunting satellites have made a number of concerning discoveries. Among them: Despite the pandemic, methane emissions from oil and gas operations in Russia rose 32% in 2020. Satellites also observed sizeable releases from gas pipelines in Turkmenistan, a landfill in Bangladesh, a natural gas field in Canada, and coal mines in the US Appalachian Basin.

At any given time, according to Kayrros, there are about 100 high-volume methane leaks around the world, along with a mass of smaller ones that add significantly to the total. Targeting emitters on a global scale from space, the European Space Agency says, provides “an important new tool to combat climate change”.

Now, Carbon Mapper is developing what it promises will be the most sensitive and precise tool for spotting point sources yet. The project aims to launch two satellites in 2023, eventually growing to a constellation of up to 20 that will provide near-constant methane and CO2 monitoring around the globe. Partners include Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the California Air Resources Board, private satellite company Planet, and universities and nonprofits, with funding from major private donors such as Bloomberg Philanthropies.

The impetus is the current global monitoring gap, says Riley Duren, a remote-sensing scientist at the University of Arizona and Carbon Mapper chief executive. “There’s no single organisation that has the necessary mandate and resources and institutional culture to deliver an operational monitoring system for greenhouse gases,” Duren says. “At least not in the time frame that we need.” Duren likens Carbon Mapper to the US National Weather Service, as it will provide an “essential public service” with its routine, sustained monitoring of greenhouse gases.