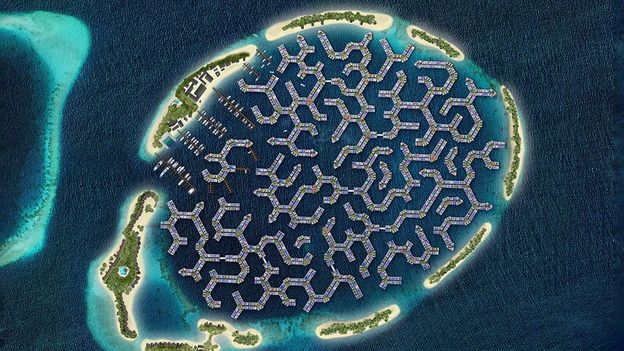

According to an FAO report, the production yields are reliable in the floating gardens, such that this system can be the best food production for 60-90% people in the wetlands of southern Bangladesh.

“Floating gardening started off as a way to raise seedlings during the monsoons, so that the farmer had some lead time at the end of the rainy season,” says Irfanullah. “But now it’s evolved to be more about food and nutritional security, disaster management, and supplementary income generation, for the poor.”

Even in the beds’ homelands of southern Bangladesh, there are concerns for their long-term future. Pravash Mandal, a farmer in Barisal district says that “floating beds cannot withstand waves, or very heavy rains and if there are tides and currents they are risk of disintegrating”. Repeated flooding also reduces the rate of water hyacinth growth, leaving farmers with little to construct their rafts.

Many rural markets are also underdeveloped, which makes it difficult for small farmers to thrive. Absence of organised agricultural markets to sell the produce, makes many farmers lose interest in these floating gardens. And it is hard to protect the crops from raiding monitor lizards and rats.

“There is scope in floating gardens, and they have been traditional methods used by farmer in south-western Bangladesh for centuries,” says Amin. But they are context-specific and its success depends on the geography of a place, he adds. Alternatives that are being practiced include vertical gardening – growing vegetables from stacks of plastic sacks, or giant containers made of plastic sheets and bamboo that are not affected by salinity – and sandbar cropping, which uses compost-filled holes in sand bars to grow pumpkins.

Irfanullah says there is a lack of long-term, rigorous study on the feasibility of the floating gardens in other parts of the country, and on just how resilient to climate change they will be. So far, the gardens are still mostly project-based and not widely adopted in northern Bangladesh.

But already, many are pinning their hopes on these small patches of safe space to grow food, in a country where the amount of agricultural land is dwindling. “For a country like Bangladesh where periods of waterlogging are increasing and becoming longer each year, floating farming is the future,” says Akter.

—

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.