At Scotland’s easternmost headland, the old fishing port of Peterhead juts out into the North Sea. “On a clear day, from the harbour you can just make out the turbines of the Hywind park,” says Alastair Reid, an economic development official with Aberdeenshire Council.

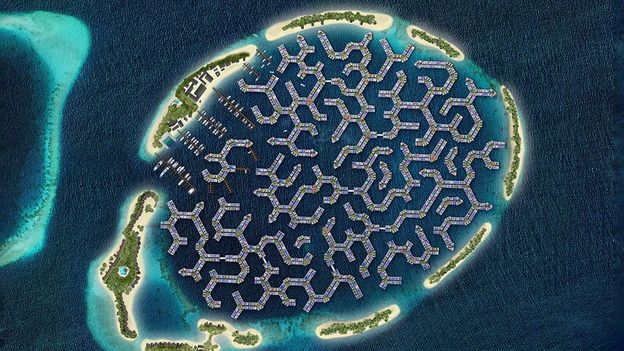

In windswept northern Scotland, where abundant wind arrays both on land and off the coast vie for limited space, the distant location of the five towering 574ft-tall (174m) turbines, 15 miles (24km) offshore, is just one novelty of this renewable energy project. Indeed, Hywind Scotland, which generates enough electricity for more than 20,000 homes, is the first wind energy array that floats on the sea’s surface rather than being dug into the ocean bed. Proponents say the technology heralds a new generation of green energy.

What’s groundbreaking about the Hywind project, located in more than 300ft (90m) of water, is that the giant masts and turbines sit in buoyant concrete-and-steel keels that enable them to stand upright on the water, much like a fishing buoy. The turbines’ nearly 10,000-ton cylindrical bases are held in place with three taut mooring cables attached to anchors, which lie on the sea floor.

You might also like:

In contrast to ordinary offshore wind turbines, with long towers sunk into the seabed and bolted into place in shallow seas 60-160 ft (18-48.5m) deep, the advantage of floating turbines is that they can access large swathes of outlying ocean waters, up to half a mile deep, where the world’s strongest and most consistent winds blow.

In Europe, where the density of onshore and near-shore wind turbines in places like Germany, the United Kingdom, and Norway has spurred increasing opposition to new arrays, the floating turbines can be installed over the horizon, out of sight of coastal residents.

“Floating wind power has enormous potential to be a core technology for reaching the climate goals in Europe and around the world,” says Frank Adam, an expert on wind energy technology at the University of Rostock in Germany.

The ocean space beyond the reach of conventional offshore turbines makes up 80% of the world’s maritime waters, opening the way for floating arrays, Adam says. “In the past few years this technology has made great strides, and Hywind shows that it can work as a whole park,” says Adam. “Now the farms have to grow bigger to show governments and investors that they’re feasible on a really large scale.”