Every one of those facilities would need to be stocked with solvent to absorb CO2. Supplying a fleet of DAC plants big enough to capture 10 gigatonnes of CO2 every year will require around four million tonnes of potassium hydroxide, the entire annual global supply of this chemical one and a half times over.

And once those thousands of DAC plants are built, they also need power to run. “If this was a global industry absorbing 10 gigatonnes of CO2 a year, you would be expending 100 exajoules, about a sixth of total global energy,” says Gambhir. Most of this energy is needed to heat the calciner to around 800C – too intense for electrical power alone, so each DAC plant would need a gas furnace, and a ready supply of gas.

Costing the planet

Estimates of how much it costs to capture a tonne of CO2 from the air vary widely, ranging from $100 to $1,000 (£72 to £720) per tonne. Oldham says that most figures are unduly pessimistic – he is confident that Climate Engineering can fix a tonne of carbon for as little as $94 (£68), especially once it becomes a widespread industrial process.

A bigger issue is figuring out where to send the bill. Incredibly, saving the world turns out to be a pretty hard sell, commercially speaking. Direct air capture does result in one valuable commodity, though: thousands of tonnes of compressed CO2. This can be combined with hydrogen to make synthetic, carbon-neutral fuel. That could then be sold or burned in the gas furnaces of the calciner (where the emissions would be captured and the cycle continue once again).

Surprisingly, one of the biggest customers for compressed CO2 is the fossil fuel industry.

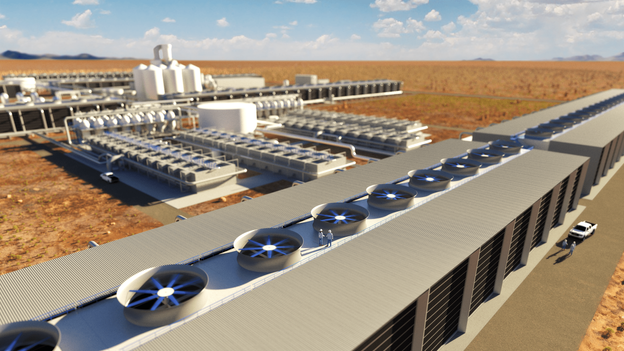

As wells run dry, it’s not uncommon to squeeze the remaining oil out of the ground by pressuring the reservoir using steam or gas in a process called enhanced oil recovery. Carbon dioxide is a popular choice for this, and comes with additional benefit of locking that carbon underground, completing the final stage of carbon capture and storage. Occidental Petroleum, which has partnered with Carbon Engineering to build a full-scale DAC plant in Texas, uses 50 million tonnes of CO2 every year in enhanced oil recovery. Each tonne of CO2 used in this way is worth about $225 (£163) in tax credits alone.

It’s perhaps fitting that the CO2 in our air is eventually being returned underground to the oil fields from whence it came, although maybe ironic that the only way to finance this is in the pursuit of yet more oil. Occidental and others hope that by pumping CO2 into the ground, they can drastically reduce the carbon impact of that oil: a typical enhanced-recovery operation sequesters one tonne of CO2 for every 1.5 tonnes it ultimately releases in fresh oil. So while the process reduces the emissions associated with oil, it doesn’t balance the books.

Though there are other uses that may become more commercially viable. Another direct air capture company, Climeworks, has 14 smaller scale units in operation sequestering 900 tonnes of CO2 a year, which it sells to a greenhouse to enhance the growth of pickles. It’s now working on a longer-term solution: a plant under construction in Iceland will mix captured CO2 with water and pump it 500-600m (1,600-2,000ft) underground, where the gas will react with the surrounding basalt and turn to stone. To finance this, it offers businesses and citizens the ability to buy carbon offsets, starting at a mere €7 (£6) per month. Can the rest of the world be convinced to buy in?