When Piet-Hein Daverveldt goes to work each morning, amid the churches and cobblestones of the Dutch city of Delft, he feels history standing to attention at his side. “Obviously, you are aware that you’re the next in line,” he says. “You stand on the shoulders of many people in the past.” At 167 Oude Delft, it’s easy to see what he means. If you stop at this address and look up you see the coats of arms, the delicate panelled windows, the stately Gothic facade finished in 1505. This is the town’s gemeenlandshuis, translated as the headquarters of the local water board, where Daverveldt serves as the chairman – or dijkgraaf as his title is known.

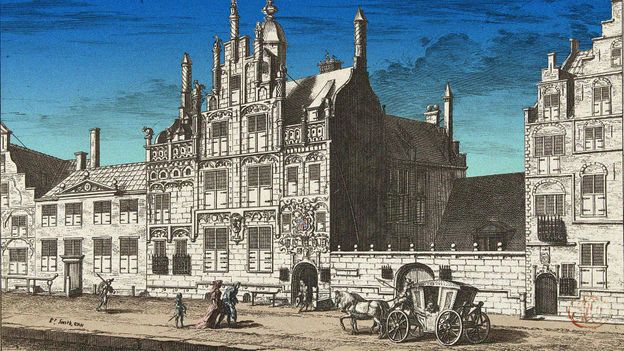

This elegant building became Delft’s gemeenlandshuis in 1645, and even that is quite new in the world of the water boards. Known in Dutch as waterschap or hoogheemraadschap, some trace their roots to the 12th Century. “Farmers, in particular, had to band together to protect their land,” explains Tracy Metz, co-author of Sweet & Salt: Water and the Dutch. “Of course, every chain is as strong as its weakest link, so there was communal pressure for everybody to do their bit to keep their farmland dry.” Even today, this still makes sense in a nation where nearly a third of the land and half of homes still lie below sea level. Dutch polders (low-lying fields reclaimed from the sea) and dikes need to be maintained collectively.

This natural vulnerability – “Netherlands” literally means “low-lying country” – helps explain the growing power of the water boards. By the time Vermeer and Rembrandt were wetting their brushes in the mid-17th Century, the boards could levy their own taxes and punish polluters. At the offices of the Rijnland Water Board in Leiden, you can still find a six-foot pole topped with an iron brand – once used to keep people in line. Even so, says Metz, the waterschaps were essentially representative bodies. Though not democratic in the modern sense, they were run communally, with farmers or burghers shaping their local organisation. Metz argues that the boards formed the basis of later Dutch democracy.

The water boards have plainly evolved from that lost age of trade guilds and ruff collars. Where once there were 3,500, just 21 remain, represented by a national association. But though their number has been cut, their role has arguably been extended: beyond organising and maintaining flood defences, they’re also responsible for water quality control, river and canal maintenance and sewage treatment. And their distinctive history still seeps into contemporary Dutch life. Apart from handsome examples in brick and stone, this can vividly be seen in the language. The term dijkgraaf, for instance, has distinctly aristocratic tones – literally it means “dike count“, serving a striking reminder of Holland’s deeply feudal past. Meanwhile, Dutch politicians use the verb polderen to describe the spirit of cooperation implicit in the water boards.

The history of the water boards has practical modern-day consequences too. Like their medieval forebears, for instance, water boards still fundraise independently. Households broadly pay two types of tax: to their municipality and to their water board. And, as Emilie Sturm argues, this independence comes with obvious financial benefits. Unlike elsewhere, where water management jostles for cash with education or housing, the Dutch model “guarantees” the coffers are always full, explains Sturm, the programme manager at Blue Deal, the body that promotes Dutch water expertise abroad. This is reflected in the statistics: the water boards generate up to 95% of their budgets via their own taxes. Compare that with the American state of Texas, where the US Department of Housing and Urban Development recently announced Houston and its county would get no new funding for flood relief – despite asking for $1.3bn (£1bn).

At the same time, the waterschaps continue their long tradition of open and elected government. Most board positions are now elected directly by the public, though a few are still doled out to corporate interests in industry, farming and the environment. Admittedly, the average Dutch person is often unconcerned with their local board: Rens Huisman of the Zuiderzeeland Water Board compares them to football referees: you ignore them when they work well. Even so, this deep well of localism is helpful. For one thing, says Daverveldt, democracy promotes transparent investing and monitoring. For another, boards are staffed with experts, elected to understand their own locality. This regionalism was on show this summer, when boards adopted varied tactics to fight the floods. In Rivierenland, crisscrossed by waterways, staff rushed to inspect the soundness of local dikes. In Limburg, squeezed between Belgium and Germany, the board has proposed a “euregional“ approach to cover all three countries.