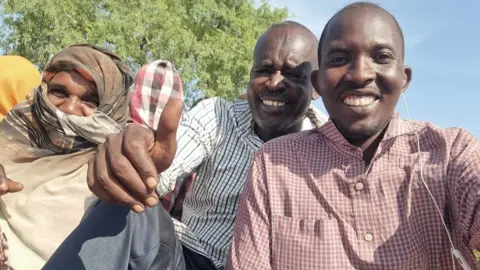

By Barbara Plett Usher, BBC Africa correspondent

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed Zakaria On the eve of his perilous escape from his home country last month, Sudanese photojournalist Mohamed Zakaria left his camera equipment with a friend, not sure if he would ever see it again.

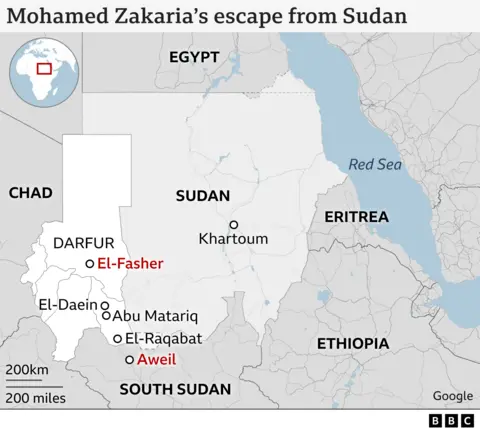

He was fleeing el-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state, which is in the grip of a punishing battle between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Mohamed had been covering this hot spot of Sudan’s 15-month long civil war for the BBC. But with the situation growing increasingly desperate, he decided it was time to escape.

The RSF escalated a siege of el-Fasher in May, targeting the last army foothold in Darfur.

Shortly afterward Mohamed’s house was hit by a shell, another struck as he was trying to get wounded neighbours to hospital. Five people were killed and 19 injured – Mohamed still has pieces of shrapnel in his body, while his brother lost an eye.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed Zakaria Two weeks later Mohamed watched his mother and three brothers depart for the safety of Chad, the neighbouring country to the west. He stayed behind to continue working to support them, he says.

But as the RSF fighters continued to close in, civilians were trapped in a war zone of indiscriminate shelling and army airstrikes, with food supplies cut off.

“I couldn’t move, I couldn’t work,” he says. “All you do now in el-Fasher is just stay in your home and wait for death… some residents had to dig trenches in their homes.”

It was dangerous to stay, but also dangerous to flee. In the end he decided to head for South Sudan and eventually on to Uganda.

He thought this journey would be safer for him than trying to join his family in Chad, and would allow him to work once he got to his destination.

From el-Fasher to South Sudan, Mohamed passed through 22 checkpoints, five manned by the army and 17 by the RSF.

He was searched and sometimes interrogated, but managed to conceal his identity as a cameraman who had documented the war. Except for once.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed ZakariaThe first stop, on 10 June, was Zamzam refugee camp on the outskirts of el-Fasher.

Mohamed and his travelling companion, his cousin Muzamil, spent the night with a friend. Here he hid his camera and other tools of the trade.

But he took with him a precious record of his photographs and videos – stored on memory cards and in two external hard drives – as well as his laptop and phone.

“The biggest problem I faced on the road was how I could hide them,” he said.

“Because these are dangerous things. If the RSF or any soldier sees them, you can’t explain.”

For the first major leg of the trek, Mohamed stashed them in a hole under the foot pedals of the pickup, without telling the driver.

He and Muzamil were held up at one checkpoint by Sudanese soldiers suspicious they were heading into RSF territory to join the enemy. But otherwise, they reached Dar es Salaam, the town that marked the end of army control, without incident.

Here they joined other travellers – a convoy of six vehicles en route to the village of Khazan Jadid.

“We paid the RSF soldiers to go with us,” says Mohamed. “If you want to arrive safely you need to pay the RSF.”

The drivers collected money from the passengers and handed it over at the first checkpoint, where one of the RSF fighters got into each car.

At this point Mohammed hid his memory cards in a piece of paper that he put with other documents.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed ZakariaAt the bus station in Khazan Jadid, Mohammed found only three vehicles.

“The road was very dangerous,” he says, “and all the cars had stopped travelling.”

But they managed to get one going to the city of el-Daein, the capital of East Darfur and they reached there in the early afternoon of 12 June.

At a checkpoint in the middle of town, those coming from el-Fasher were put to one side, says Mohamed, under suspicion that they had worked with the army.

Here’s where he ran into trouble.

He had deleted all the messages, photographs and apps on his mobile phone.

But the RSF officer found a Facebook account he had forgotten to remove, complete with posts he had shared about the bombing of el-Fasher and the suffering of civilians.

There followed an hours-long interrogation where Mohamed was separated from Muzamil and accused of being a spy.

“I was threatened with torture and death unless I disclosed the information I had,” he says.

“I felt lost. It was a very bad situation. If he wanted to kill you, he could do it and no-one would know. He can kill you, he can beat you, he can he can do anything to you.”

Mohamed was finally released at 19:00 after negotiating the payment of a large sum of money.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed Zakaria“This was the worst moment,” he says, reflecting on the experience, “not only in the journey but I think the worst moment in my whole life… because I didn’t see any hope. I can’t believe I’m here.”

Mohamed suspected his interrogator would alert another checkpoint down the road to arrest him again.

He and Muzamil raced to the station to get out of town as fast as they could. There was only one vehicle, a pickup truck that was crammed full, but they managed to squeeze into a small space on the roof.

They made it as far as the village of Abu Matariq, where the engine broke down and took two days to fix.

Having survived arrest Mohamed was anxious to get to South Sudan as quickly as possible. Instead, he faced a lengthy delay.

The travellers finally left Abu Matariq on 14 June heading to el-Raqabat, the last town in East Darfur before the border. The way led through the forest of el-Deim, a flat expanse of grass and sand sprinkled with acacia trees.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed ZakariaHeavy rains slowed and then stopped their progress, as the pickup got stuck in the mud. They were stranded.

“It was a severe ordeal,” says Mohamed.

“We spent nearly six days without drinkable water and food. We mostly relied on rainwater and dates.”

In a stroke of luck, they were able to buy two sheep from passing shepherds.

During the course of the journey, says Mohamed, he did not have trouble getting food. The RSF-controlled areas through which they passed had seen battles early in the war, but had stabilised somewhat since then.

Markets and small restaurants were operating. Food was expensive, but not “super expensive” like in el-Fasher, where many people were forced to ration themselves to one meal a day.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed ZakariaIn the forest, the men slept in the open, sometimes in the rain, while the two women and two children in the party stayed inside the vehicle. They had to pick thorns out of their feet from walking without shoes in the mud.

Eventually they pushed the pickup back onto solid ground. But the engine worked only sporadically because of a weak battery. And then it ran out of fuel.

At this point two of the men set off to find the nearest village. It turned out to be a nine-hour walk. To everyone’s relief they returned late in the day with extra fuel and another vehicle.

Arriving in el-Raqabat, Mohamed and Muzamil were just a 15-minute drive from South Sudan and safety.

But the next morning before the travellers could start out, they were picked up and taken to the main RSF office and interrogated for three hours.

Someone had reported that members of the Zaghawa ethnic group had entered the town. That included Mohamed, as well as the family sharing the car with him.

The Zaghawa make up one of the armed groups fighting alongside the army in el-Fasher, and the RSF view them as enemies.

Mohamed stashed his memory cards, hard drives and laptop with one of the women and told the RSF officer that he was a computer engineer.

Once again it came down to a pay-off: 30,000 Sudanese pounds ($50; £39) from everyone. Mohamed and a few other members of the group paid extra to release another man who had been found with a photo of an army soldier on his phone.

Then Mohamed and Muzamil clambered into a motorised rickshaw and headed for the border.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed ZakariaCrossing into South Sudan on 20 June was an “unbelievable” moment for Mohamed.

“When I saw the South Sudanese men, I thanked God and prayed,” he says. “I felt I’m alive. I really didn’t believe that I am alive, that I am here. I reached South Sudan with all my data and my laptop, even though I had many encounters with the RSF.”

He called his mother as soon as he was able to buy a local SIM card. “She didn’t believe that I was alive,” he says.

Mohamed had been out of internet range for 11 days, and his family had no idea where he was or what was happening to him during that time.

“They were very very worried,” he says. “Most of them had told me you must not try this road, don’t go, you can’t make it.”

But he had made it.

He stopped in the South Sudanese city of Aweil for a few days, where the Zaghawa family he had been travelling with hosted him in their home.

He then moved on to the capital, Juba.

Muzamil decided to stay there, but Mohamed travelled to Uganda and registered as a refugee at a camp near the border because his passport had expired.

Mohamed Zakaria

Mohamed ZakariaTwenty-three days after leaving el-Fasher, Mohamed arrived in the Ugandan capital, Kampala, on 3 July. He is staying with his uncle.

“I honestly have no idea where life will take me from this point,” he says.

His immediate priority is to look after his family and try to reunite them. Besides his mother and three brothers in Chad, he has a brother in Turkey and a sister in the United Arab Emirates.

His dream for the future is to return to Sudan in more peaceful times and set up a university in Darfur to teach filmmaking, photography and media studies.

“My work did not end after leaving el-Fasher,” he says. “I believe that was just a phase and now I have really begun arranging the second phase by working to convey the truth of the situation there.

“I hope that my effort, even if just a little, will help shorten the duration of the war and save the people in el-Fasher.”

More about Sudan’s civil war from the BBC:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC