By Nicola Bryan, BBC News

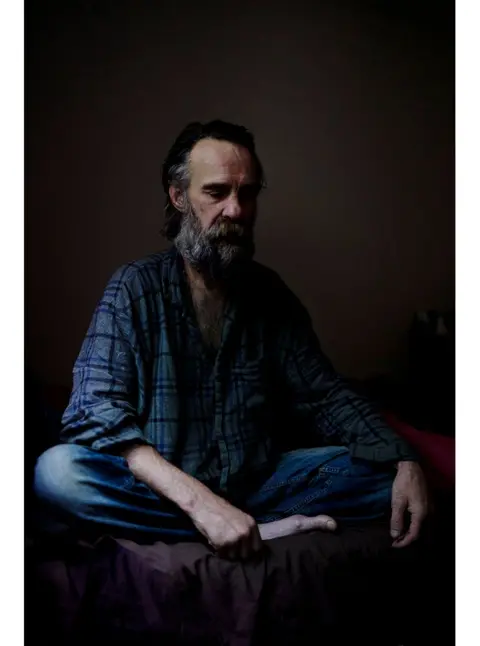

Nik Roche

Nik RocheOn a wet day a man was shouting and swearing in the street, and passers-by crossed the road to avoid him.

But Nik Roche instead decided to approach the man in Swansea to find out what was wrong.

It was the start of a friendship between him and Tony that would see the men living together and Nik documenting his new friend’s unconventional and sometimes chaotic life through photography.

“I’m a fully immersive documentary photographer, so I make friends, I form relationships and trust and then I make pictures – eventually,” explained Nik.

“I don’t go in to make pictures, I make them eventually if it feels right.”

Nik Roche

Nik RocheOn the day they met, Nik discovered Tony was distressed because he had gone into a bar, ordered a drink, discovered he did not have enough money to pay for it, had left to go to a cashpoint and could not find the bar again.

“I just strode back into the bar with him, we sat there and two-and-a-half years later we were the best of friends and I ended up living in his house,” said Nik.

“Tony had a house in the Clydach area of the city, but chose to live in an Arctic bell tent in the woods behind it.

“He would do whatever was in front of him sadly… but I wouldn’t have called him a major drug misuser.”

Nik Roche

Nik Roche “He needed a few cans to function in the morning.

“Then two or three more and a switch would go off and you’d see drunk Tony – but I wouldn’t put him in the same class as many, many, many, many others I’ve met.”

Nik said Tony never had money for his prepayment gas and electric meter so “for something like 29 days in November he maintained a fire in his garden that never went out all around the clock”.

He said his collection of candid shots of Tony – titled As Far as They’re Concerned We Are a Normal Family – only came about once he had “got across that it was not a performance that I was looking for, it was a friendship and a relationship”.

Nik Roche

Nik RocheRoche, 53, a landscape designer, began taking photographs only six years ago.

After taking a short photography course in Cardiff he went on to complete an MA in documentary photography from the University of South Wales.

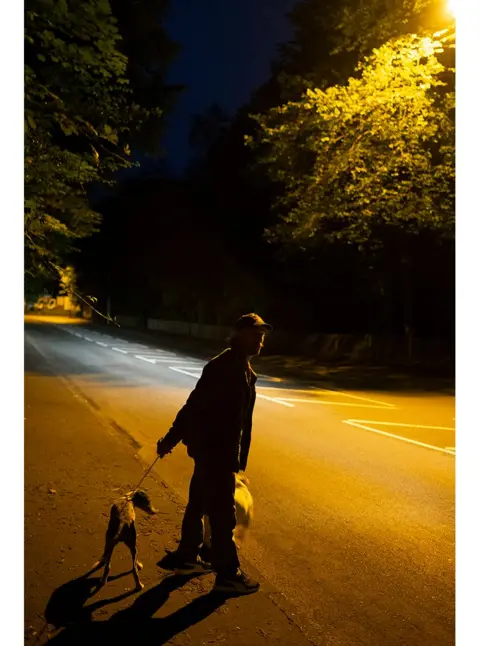

He said his work was “about notions of home and family and love”.

“What interests me is people who find that outside of societal norms,” he said. “My work is not about poverty, it is not about drug misuse.

“It’s quite easy to dismiss my work and go ‘oh, it’s poverty porn or it’s voyeuristic’ – it’s none of those things but I can see how easy it can be to dismiss it as that.”

Nik Roche

Nik RocheNik said he had always “gravitated towards people who have struggled a bit”.

He spent four years volunteering for a homeless charity where he witnessed the same people “always finding themselves back in this system, back in this loop… no matter how much help and how much support is there”.

“The only thing I could see that connected everybody was a shared trauma, a childhood trauma,” said Nik.

He said his photography was a way of “looking for some answers”.

“I’m not trying to save anybody or save anything, I’m just trying to have conversations about things,” he said.

Nik Roche

Nik RocheNik has used his immersive style of photography to capture several people whose lives are affected by addiction, poverty and insecure housing, most of whom he has “grown to love dearly”.

But he became particularly close to Tony.

“I felt more than comfortable working with Tony because I felt like we shared vulnerabilities, I didn’t feel like I was tapping into his,” he said.

“I get anxiety every day, I take antidepressants, I self-medicate in that sense.

“I’m no different, it’s just I’ve maybe got a support network that doesn’t allow me to fall that far.”

Nik Roche

Nik RocheTony died from an overdose two years ago. He was 60.

His death has hit Nik hard.

“Tony became my dear friend,” he said.

“I was really hurt, I really missed him, it was very difficult. I haven’t made any pictures since hardly.”

Meeting Tony has no doubt changed Nik’s life.

“I’ve been living in a caravan for the last two-and-a-half years because at the first opportunity, when I could, I wanted to experience what it was like to live his life while I was making the work with him,” he said.

“So I’ve been living as best I can, or as close as I can, to the life that he lived.”

Nik Roche

Nik RocheHis immersive way of taking photographs sounds all-consuming – does he never want to close the door on his work at the end of the day?

He joked: “I was only doing a short course and then an MA and now I sort of became them [the people he photographs] almost – minus the intravenous drugs obviously.”

He insisted his work was more uplifting than the images may suggest.

“I often work in what appear to be really dark situations but when you’re there there’s laughter,” he said.

“We laughed and had more beautiful moments than you might expect from looking at the pictures.”

Nik Roche

Nik Roche