In 1971 Brazil, most people would think long and hard before going anywhere near General Emilio Garrastazu Medici. The country’s then-president was a fearsome figure whose brutally repressive military rule relied on systematic torture and the assassination of dissenters. But Lea Campos was about to go and see him.

Campos believed Medici could help in her power struggle with Brazil’s sporting authorities – led by the all-powerful Joao Havelange, who would soon become president of world football governing body Fifa.

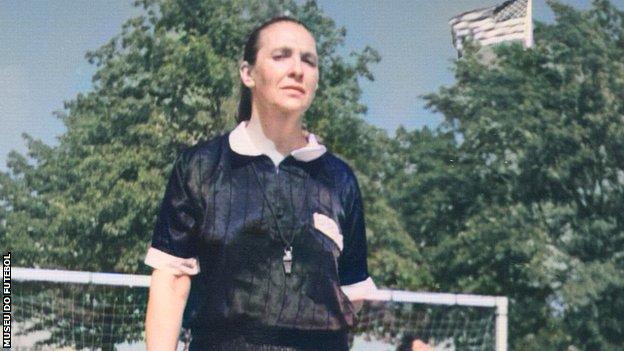

Four years earlier, Campos had qualified as a referee. She was one of the first women in the world to do so but the CBD, the authority that ruled over all sport in Brazil, refused to let her work.

The South American country was one of many where organised women’s football was banned – England was another. As a matter of fact, legislation passed in 1941 excluded women in Brazil from a series of sports. Havelange, who had presided over the CBD since 1958, believed that the ban also applied for refereeing. According to Campos, he made his views quite clear.

“Havelange first told me that women’s bodies weren’t suitable for refereeing men’s games,” Campos, now 77, tells BBC Sport.

“He later said that things like having periods would make my life difficult. He ended up insisting that women would not be referees for as long as he was in charge.”

It was not the first time Campos found herself battling for a break into the sport she loved.

Born in 1945 in Abaete, a small town in the south-eastern Brazilin state of Minas Gerais, Campos became interested in football at an early age and fondly remembers kicking improvised bundles made of socks. She faced discouragement from all sides.

“I was always trying to play football with the boys at school, but teachers would stop me and say it wasn’t appropriate,” she recalls.

“As for my parents, they also said that it wasn’t something for a lady to be involved with.”

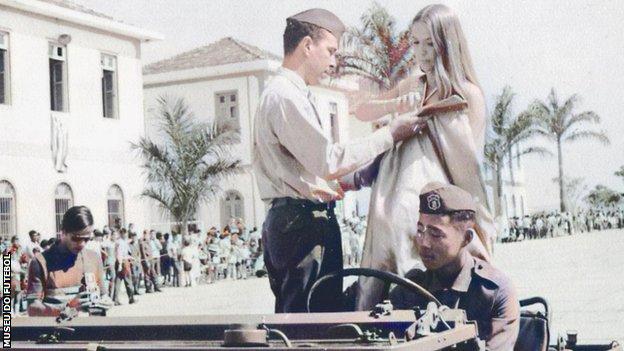

Her mother and father nudged her into beauty pageants instead. She would routinely win the contests and, ironically enough, one of her triumphs, in 1966, ended up helping her land a job in public relations with top flight side Cruzeiro.

Campos travelled with the team all over the country, her interest in football rekindled. And then it dawned on her. Maybe there was a way for her to get more involved in the game after all.

“If I tried to play, it would have been impossible to get support for the cause, as it was actually illegal for women to do it at that time,” she says.

“But being a referee was a way to get in. There was nothing specifically against it in the law – women were banned from kicking a ball there was no mention of blowing whistles.”

In 1967, Campos enrolled on an eight-month refereeing course and passed in August. But she may not have been the first woman in the world to do so – identifying football’s first female referee is harder than first appears.

In 2018 it was reported that Fifa had recognised a Turkish woman, Drahsan Arda, as the first, in a letter sent to her. Arda received her referee’s licence in November 1967, taking charge of her first match in June 1968. She sent supporting documentation to Fifa and received a reply, which Fifa says was misinterpreted; it simply recognised she was one of football’s first female referees.

Another candidate has recently been brought to its attention – Ingrid Holmgren, a Swedish woman who is believed to have qualified in 1966. Then there is Edith Klinger, an Austrian thought to have worked as a referee in 1935.

Fifa does not feel able to say with certainty who was the first but it acknowledges the importance of researching this and is keen to help investigate further.

What can be said definitively is that Campos was one of the first. But qualifying from her course was just the start of a long battle with the patriarchy of the CBD. After she finished her studies they refused to give her a licence, claiming the legislation that banned female footballers in Brazil also banned female officials.

“I sought legal advice and was assured that there was nothing in the text that made that distinction,” Campos says. “But the authorities did not want to listen.”

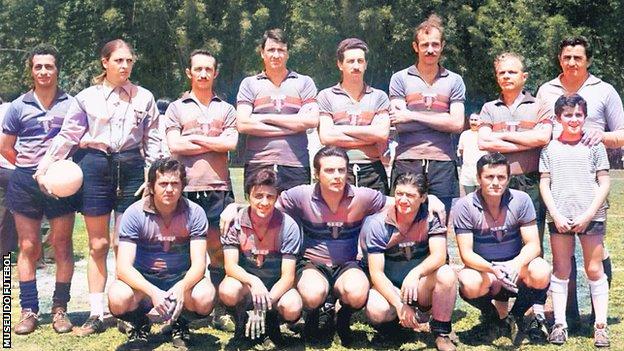

What followed were years spent pleading her case with the CBD and Havelange. She sought to raise awareness by organising friendly matches where she could officiate, some involving women players, which were often broken up by police. In times of severe repression in Brazil such ‘dissent’ wasn’t taken lightly; Campos claims she was arrested “at least 15 times”.

But in 1971 she received a letter that gave her extra energy to fight her cause: an invitation to participate in the unofficial Women’s World Cup in Mexico. She did not want to let the chance pass, but needed to get past Havelange, until then an unmovable obstacle.

The only way was to resort to a superior power. For a second time, Campos’ beauty pageant past came to her aid.

One of the many beauty contests Campos had won was ‘Army Queen’ for the Minas Gerais region. She pleaded with a local commander to help her secure an audience with President Medici, who was soon to visit the state capital, Belo Horizonte.

She was granted three minutes. She told him she needed him to overrule Havelange.

“Medici looked at me and said he’d like me to meet him at the presidential palace in Brasilia in a couple of days,” Campos says.

“Needless to say, I was scared. We were under a dictatorship, and I was challenging the system. Thoughts of being arrested or ‘disappearing’ raced through my mind.”

Campos duly flew to Brasilia and was received by Medici for lunch. To her astonishment, he delivered her a letter requesting Havelange grant her refereeing licence. The general also made a surprise revelation: she had fans in the president’s inner circle.

“One of Medici’s sons followed my career very closely and even had a scrapbook with pictures and newspaper articles about me,” she says. “His collection was even bigger than mine!”

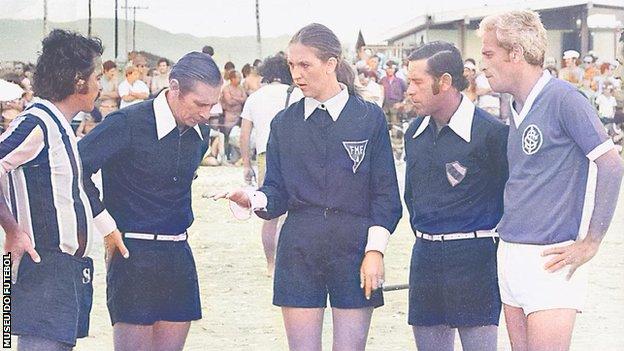

Perhaps that was the reason behind Medici agreeing to pull rank on Havelange. Either way, not even the larger-than-life future Fifa president would dare question his orders. In July 1971 Havelange called a press conference and said that following “a change of heart” Campos would now be allowed to work as a referee.

Campos adds: “He even made a speech to the press saying he was honoured to announce that Brazil would have the world’s first female referee and that it was happening on his watch.”

A few weeks later, she travelled to Mexico but unfortunately fell ill with the effects of altitude in Mexico City and was not fit to referee. When she got back home she was finally clear to do her work, but having a licence did not protect her from prejudice.

Most of the 98 games Campos officiated were lower division matches, all over Brazil, in which the presence of a female of referee was sold as some kind of exotic attraction.

Intimidation and sexism were a constant presence in her work – newspapers printed several cartoons of dubious taste. One of them suggested players would be aroused by a female referee.

She recalls an under-23 fixture between bitter state rivals Cruzeiro and Atletico Mineiro in 1972.

“Before the match, an Atletico director approached me and lifted his shirt,” Campos says. “I could see he had a gun.

“Cruzeiro won 4-0 and after the game I saw the same man in the tunnel. I asked him if he still wanted to shoot me. Instead, he gave me a hug and said I’d had a good game.”

On the whole, Campos says, she wasn’t treated any differently than a male referee.

“OK, sometimes players would get a bit angry,” she adds. “There was one who refused to leave the pitch when I sent him off. There were other occasions when players would tell each other off for swearing in front of me. Most of the time I felt really respected.”

She was also happy. But then came a horrible, life-changing accident.

In 1974, Campos was traveling on a bus that ploughed into the back of a lorry. She suffered horrific injuries to her left leg, which barely escaped amputation. To add some bitter irony to the accident, the bus she was traveling on belonged to a company owned by the Havelange family.

Campos underwent more than 100 surgeries and spent two years in a wheelchair. Part of her treatment took place in New York, where she met Luis Eduardo Medina, a Colombian sportswriter whom she would marry in the 1990s, moving to the United States.

In America, she reinvented her life as a confectioner and found particular success among the Brazilian expat community in the New York and New Jersey area. In later years, her health deteriorated, and she had two heart attacks. But her most difficult time came in May 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic struck: her husband Luis lost his job and the couple had severe financial difficulties. At one point, they had to live in a friend’s house as they’d become homeless.

It was then that a crowdfunding campaign among Brazilian referees raised enough money for Campos and her husband to rent an apartment in New Jersey. They are weathering the storm for now.

“What they did was beautiful, and I am really grateful,” Campos says. “It made me think that all my struggle wasn’t in vain and that I have left a legacy.”

She also speaks with pride when considering how women referees are gaining ground in the game. She “punched the air” when French referee Stephanie Frappart became the first woman to officiate a men’s Champions League match in 2020.

“I felt Stephanie’s success was a victory for me too,” Campos adds.” It dawned on me that everything I went through was worthwhile. I felt like an old tree that could still bear fruit.”

She also feels Frappart’s landmark was long overdue. Women referees may have come a long way since the 1970s, but Campos still believes there is a lot of prejudice around.

“Why has there never been a woman officiating a men’s World Cup game?” she asks.

“I really expected things to have evolved a bit more. Men and women referees go through the same rigorous training so why keep them apart? It’s ridiculous.”