Until recently Andy Cameron did not know he still has a certificate that rightfully belongs to Ben Stokes.

It was printed about 19 years ago and has survived a flood in the garage and a house move. It congratulates a 12-year-old Stokes on being selected for the Wellington junior representative team. His family moved to England before he could receive it.

The job taken by Stokes’ father Ged as head coach at Workington Rugby League Club is etched into the lore of English cricket. It set Stokes on the path to becoming one of the most storied and influential players to ever pull on an England cap.

This week Stokes, now 31, returns to Wellington – the city that was home for his last two years as a New Zealander – for the second Test against the Black Caps, the first time he has played a Test in the capital.

He does so having revolutionised the fortunes of his England team by championing a style that is breathing life into the Test format.

It was in the indoor nets at the historic Basin Reserve ground where Cameron first set eyes on Stokes.

“Ben always stood out, not because he was bigger than anyone else, but because he was a powerful boy,” Cameron tells BBC Sport.

“When he threw the ball at you, you felt it in the gloves. He had great natural ability and great skills at other sports. He was adept at picking the ball up with either hand.

“If you threw him the ball and said ‘hey Ben, bowl a leg-break’, he’d know exactly what to do, whereas most others boys wouldn’t know what you were talking about. He just knew instinctively what to do.”

Stokes’ roots are in Christchurch. He was born there and his mother still lives there. The largest city on New Zealand’s south island is also where Stokes began his cricketing career.

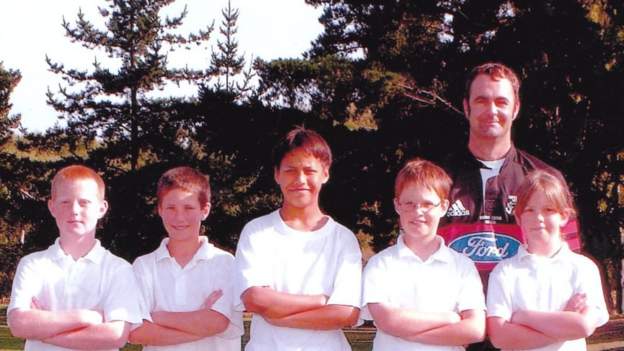

The picture at the top of this page is a nine-year-old Stokes lining up for Merivale Papanui Cricket Club in the 2000-01 season.

“Congratulations to Tim Johnston, Sam Miles, Ben Williams, Adam Hogan, Ben Stokes and Nick Birchfield for gaining selection in various Canterbury under-age teams over the season. A few names to look out for in the future!” reads a Merivale Papanui annual report.

Indeed, Mark Shaw, the coach in the picture, thought it was Miles who was more likely to go far in the game.

“Sam Miles was the boy I would have said would go on to play for New Zealand, but he ended up playing soccer,” says Shaw. “Ben was the kid who just wanted to succeed. He wanted to be the guy that scored the runs and he took the wickets.”

Shaw still has a framed collection of pictures of Stokes’ Merivale Papanui team. In the centre is a group shot, surrounded by an action image of each player. Stokes is keeping wicket.

“Ben wanted to turn a game,” says Shaw. “He would bat, bowl, then put the wicketkeeping gloves on to take a winning catch.”

It was Ged’s job that took the family to Wellington when Stokes was 10. He attended Plimmerton Primary School, where he met teacher and cricket coach Mike Smellie.

“The first time I noticed Ben he was out on a sports field playing touch rugby with kids three years older,” says Smellie.

“I remember seeing him get the ball and run at these big kids. He stood up the first guy, then he ran an angled run off towards the corner flag. The defence sucked into him and he passed the ball, a clean 20m pass to the winger, who scored in the corner.

“I thought ‘you couldn’t have done that any better – who are you?'”

Smellie would get to know Stokes in the classroom, teaching him for a year.

“One time we were doing some writing on the topic ‘what is the thing you are most scared of?'” explains Smellie.

“There were kids who were scared of the world ending, or being chased by vampires. Ben wrote about having to face a bowler called Tipene Friday in a game of cricket – he was a young boy of Ben’s age who liked to drop them short.”

Friday went on to have a brief career in first-class cricket before becoming a professional basketball player. Even if Stokes did have a fear of Friday’s bowling, he was about to reveal his own rare cricketing ability.

“I first saw him play cricket in trials for the school team,” says Smellie. “Young kids usually want to pull, hook and hit the ball behind square. Ben would hit them out of the school ground, aged 10, straight. He could absolutely smash it.”

Plimmerton took part in the Milo Cup, a national knockout tournament. A smallish school, they didn’t often make great progress. With Stokes in the team, they went on a cup run.

“We kept winning. We won and won and won, and Ben was consistently making big scores,” says Smellie. “We were calling ourselves the juggernaut. We got through to play Palmerston North, a much bigger school in a massive cricket area. We were on a hiding to nothing, 100-1 and drifting.”

There was just one problem – Stokes was out of the game with a broken arm.

“I was asking if he could play and he said he had another three weeks in plaster,” says Smeille. “I rang his mum, pretending to talk about something else. We got on to cricket and she said no. The day before the game, I was talking to him and said he might as well come to watch.”

At this point it is worth remembering that Ged had part of his left middle finger amputated because he saw that as a better option than missing rugby matches. It is the reason Stokes celebrates centuries with the middle finger on that hand folded down, as a tribute to his late father.

“The next day, he walked up the school driveway, pulling his cricket bag with no cast on his arm,” Smellie continues. “I said ‘what’s going on?’ He said ‘Dad got out the scissors and cut it off this morning’.”

Stokes got a hundred, albeit in a losing effort to the eventual national champions. Around Christmas of 2003, he left Plimmerton and moved to Cumbria. By the following summer he was in the county’s age-group representative team. The next time he took the field in New Zealand, he was playing for England in the 2010 Under-19 World Cup.

“He had been a true blue Kiwi boy,” says Smellie. “I couldn’t believe how in six short years he had become completely English. There was not a hint of Kiwi in his accent.”

Shaw also caught up with Stokes during that tournament, the day he scored a hundred in Lincoln against an India side containing KL Rahul and Mayank Agarwal, but Stokes couldn’t recall his time playing in Christchurch.

Still, when he would later return to the city as a full England international, Shaw was able to get Stokes to sign the picture of the Merivale Papanui team.

“I got my hands on the picture and ended up at the Papanui Working Men’s Club that night,” said Shaw. “The photo went amiss and I never saw it again. I’d like to know what happened to it.”

As for the certificate, Cameron is sending it to Wellington in order for it to get to Stokes during the Test at the Basin Reserve. It is evidence of a sporting sliding-doors moment, a parallel universe where Stokes wears a black cap and becomes a Kiwi icon.

New Zealand’s loss is England’s immeasurable gain.