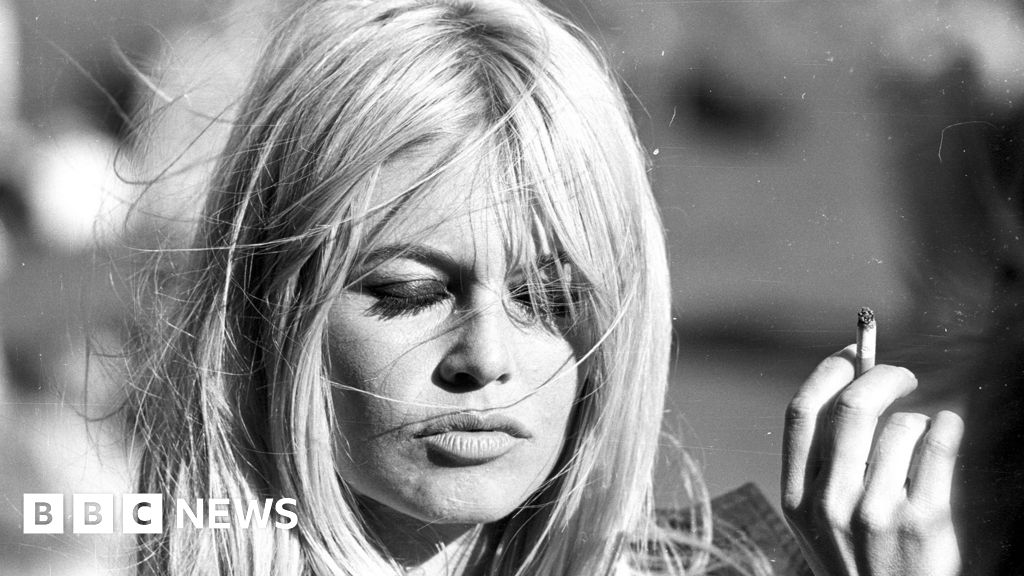

Ceridwen Hughes

Ceridwen HughesIn a bid to avoid awkward questions and stares from strangers, Jono Lancaster makes a point of smiling and saying hello to everyone he meets.

“I’m creating a positive interaction before they even see me, or say anything, or think anything… I’m taking ownership of it,” he said.

Jono has Treacher Collins syndrome, a condition caused by a genetic mutation which affects the development of the facial skeleton, cheekbones, jaws, palate and mouth.

He is one of several people with a visible difference who have taken part in project Rarely Reframed by Welsh photographer Ceridwen Hughes.

The portraits, inspired by the paintings of the Dutch Masters, aim to tell the stories of people who are rarely positively depicted in art and question our biases towards supposed perfection.

Jono, 39, from Normanton in West Yorkshire, said he accepted people, especially children, were always going to be curious.

“I went into a school recently and a child came up to me and said, ‘Your face looks funny,’ and I was like, ‘Oh, yeah, I was born like this’,” he said.

“She looked at me and said, ‘Alright, cool, can I show you the pirate ship?'”

He said this was a fairly typical encounter – once a child has an answer to their question they are generally satisfied.

Ceridwen Hughes

Ceridwen HughesJono is due to travel to the US and is already anticipating being in an airport full of curious children.

“They’re going to be staring and I know what to do,” he said.

“If they’ve got a cute suitcase I’ll say, ‘Oh, I love your suitcase! Where are you going? Oh, I’ve never been there!’… it’s trying to create that positive experience for myself and the individual.”

Having to be constantly proactive sounds exhausting – does he ever want to just step out of his door without having to engage with everyone?

“One of my self-care routines is sitting at home without a smile on my face,” he laughed.

“I’m done smiling, I’m done talking, I’m done educating. I am very aware that I need time on my own to recharge.”

When asked how parents should react when their child points out a stranger’s differences, he said they should try to turn it into a positive experience.

“Once they have a little bit of knowledge, or a little bit of an answer, kids usually accept that and they move on,” he said.

“By telling them to be quiet, or ‘Shhhh, we don’t want to offend that person, come away’ that’s not going to help. That’s just going to increase that curiosity.”

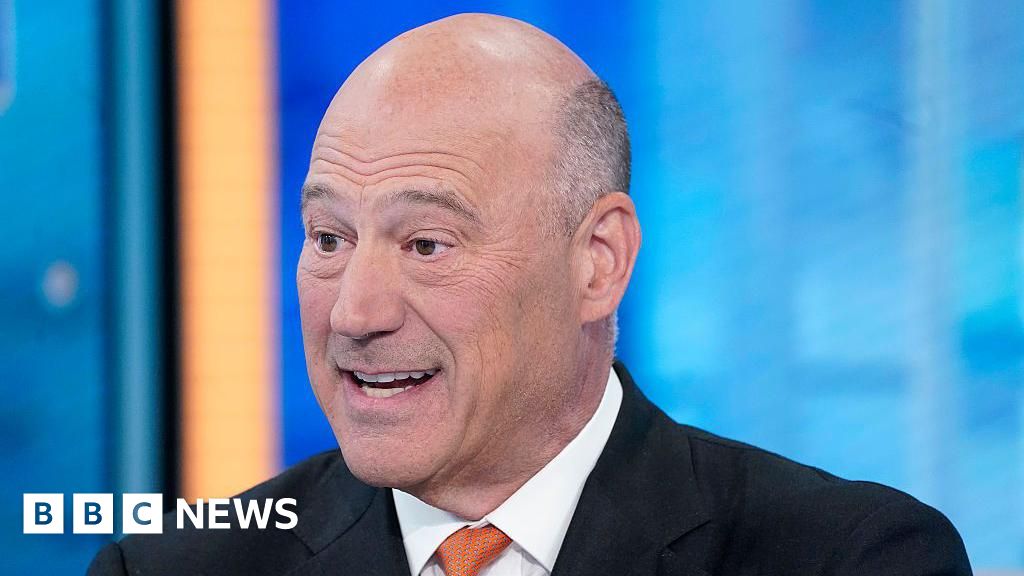

Ceridwen Hughes

Ceridwen HughesAmba Smith, who also features in the exhibition, has a birthmark that stretches from her head to her toes and also affects her internal organs.

The 23-year-old from Lincolnshire, recalled a situation when she was about eight years old and a parent dealt with their child’s curiosity brilliantly.

“The little girl said, ‘Oh, mummy, what’s that on that little girl’s face?’ And the mum handled it just so beautifully. She knelt down to her daughter’s level and said, ‘Oh, it’s a birthmark, it’s pretty, isn’t it?’ And then the little girl responded, ‘Oh, yes, it’s really pretty, mummy’.”

Amba, whose birthmark is one of a number of features of Sturge-Weber Syndrome, said finding self-acceptance was an ongoing journey.

“There’s definitely times where it’s gone one step forward and three steps back,” she said.

Ceridwen Hughes

Ceridwen HughesShe started using camouflage make-up from the age of five and from the age of about 11 began fully covering her birthmark and wearing clothes that hid her body.

These days she still covers up on days when she’s “not feeling the greatest version of myself” – but also likes to wear her make-up in a more creative way.

She said seeing films such as Wonder and The Greatest Showman as a teenager had been a positive turning point for how she felt about herself.

Meeting others with visible differences who were also working to “change those stereotypes of what beauty is” had also been important.

“Most of us have had the same experiences growing up, maybe with bullying or trolling and I think that kind of just unites us all together,” she said.

Ceridwen Highes

Ceridwen HighesKatja Taits, 23, from St Albans, Hertfordshire, has Moebius Syndrome, a condition that causes facial paralysis.

She said growing up she did not experience bullying but struggled with other people’s misconceptions of what she was capable of.

“I would have sheets printed out with bigger writing for me and I was perfectly capable of reading normal size sheets,” she said.

“So as a teenager I was like, ‘Why am I treated so differently for no reason?’ It really frustrated me because I felt really singled out and I didn’t want to be.”

She said she had not always been entirely self-accepting, but had now reached a point in her life where “I kind of like the way I look”.

But, like Jono, she finds herself chatting to strangers in a bid to control interactions.

“It would be nice in the future if we didn’t all have to make such an effort to just sort of exist in public spaces and just be there without having people thinking, ‘What’s wrong with you?'” she said.

Photographer Ceridwen, from Mold in Flintshire, has a son with the same condition as Katja and runs non-profit group Same But Different.

Her exhibition can be seen in the latest edition of online magazine Rarity Life, but she would like to see images like these “sitting alongside every other image in exhibitions and galleries so that it’s the norm and not something that’s different”.

“It would be really nice if these sorts of projects weren’t needed, but at the moment unfortunately we still need to give a stronger voice to people who aren’t necessarily being seen every day,” she said.

When it comes to representation, Jono is feeling optimistic for the future.

“What excites me is that this generation here in 2024 is loving themselves, they’re celebrating themselves… saying, ‘This is me’ – they’re calling people out and making change,” he said.

“Every single one of us has all these beautiful, unique stamps across our bodies, our faces, our personalities and our characters and they need to be celebrated and not hidden.”