By Natalie Grice, BBC News

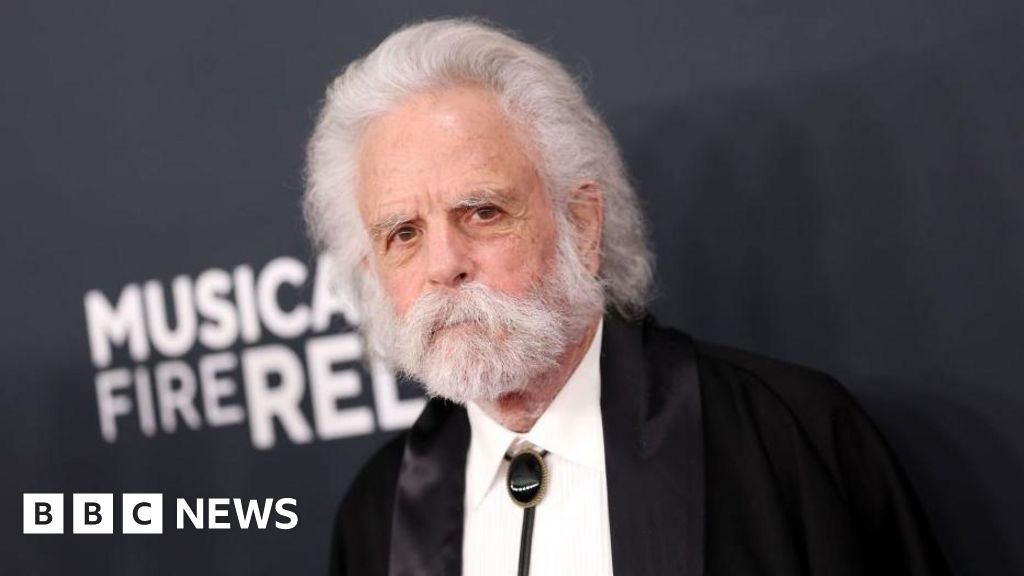

Roger Tiley

Roger Tiley“I was planning to go and find a war or something when I finished my course. And in a way the war was on my doorstep.”

The “war” referred to by photographer Roger Tiley is the 1984-85 miners’ strike that began a few short months before he was due to finish his degree in Newport, and which altered the course of his emerging professional life.

It saw him roam the south Wales valleys, showing the mining community he had grown up in as it battled for its very existence, sending his photographs off to newspapers in London.

The year-long strike ended in defeat for the miners, and was followed by the rapid closure of the pits that had formed the backdrop to Roger’s life.

Now he has retraced his steps across the coalfield from the south-east Wales valleys where he grew up to his present home in the Swansea valley, to raise money for the Alzheimer’s Society and look at the transformation of the landscape in the intervening decades.

As a local boy, Roger had already spent some time taking pictures in the collieries in the year or so before the strike began, and this relationship allowed him access to communities which knew and trusted him.

“I’m originally from Cross Keys in the Gwent valleys and some of my friends went to work in the collieries,” he said.

“Jobs didn’t seem to be much of a problem in the 1970s. If you wanted to work, you could get a job in a factory, in the steel industry or in the collieries. Within 10 or 15 miles of me there were quite a few collieries still working, around about eight.

“The miners’ strike was very hard but I think I look back on it with fond memories in the fact that people were so good to me and so helpful.

“It’s a time that was desperate for a lot of mining families up in the valleys and I think what they were fighting for I believed in.

“I was very careful of where I turned the camera because I didn’t want anybody using the pictures in the way that I didn’t intend them to be used.”

Roger Tiley

Roger TileyIn between taking photographs, Roger also got involved with helping support the miners and distributing food parcels, which he “really loved. I’m proud I had the opportunity to do that.”

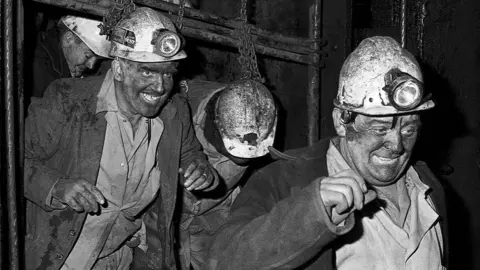

One of the sites that holds particular resonance for him is Celynen South colliery near Abercarn in the Ebbw valley, where he first documented the working life of a colliery.

“That’s where I started taking pictures. I wrote to the manager and he said I could come up,” he explained.

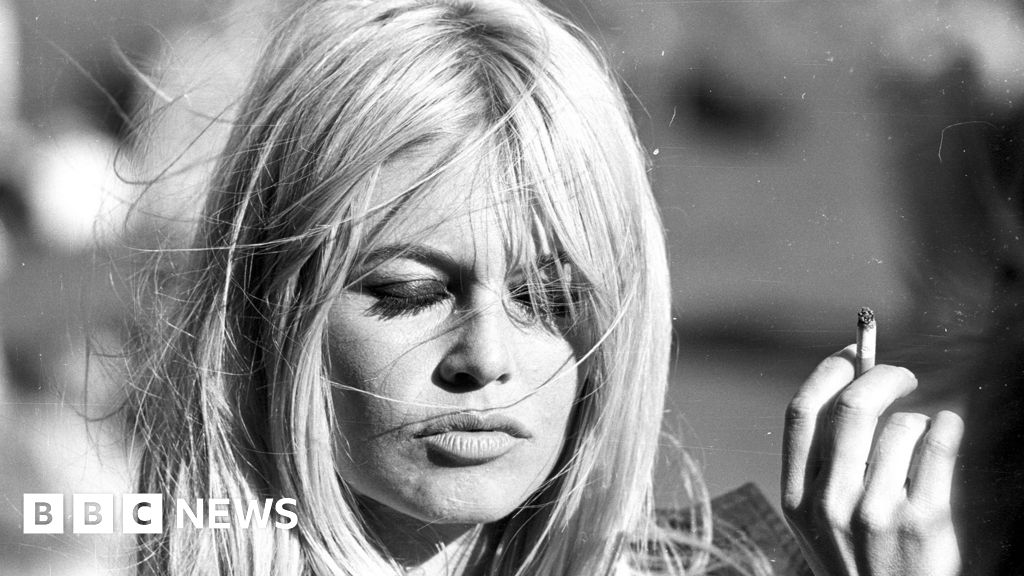

“There’s two miners waiting to go underground and there’s a pithead wheel in the background and it’s a very graphic picture. Over the years it’s been used time and time again.”

Roger returned to the closed pit after the strike ended and he was commissioned to document the impact it had had on the valleys.

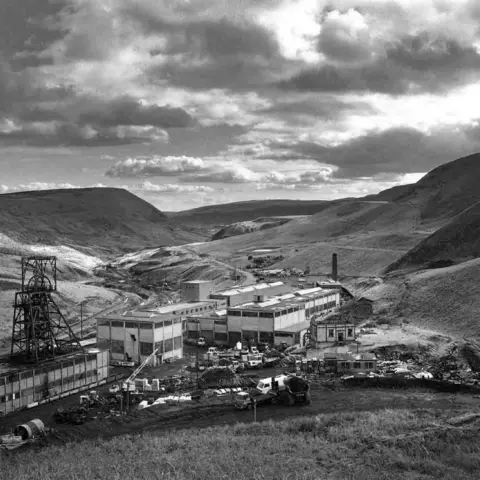

Roger Tiley

Roger TileyRoger returned to the closed pit after the strike ended and was commissioned to document the impact it had on the valleys.

“One of the first set of pictures that I took of the actual area, the landscape, was Celynen South. It was very sad. In those days they didn’t fence things off. They just demolished the pit and you could just walk on to it, which I did.

“Some of the buildings were demolished, the pithead wheel was there but some of the ropes they used for the cage had gone. It just looked really sad.”

“There’s a housing estate on the colliery site now. There isn’t anything really to mark that there was a pit there.

“In a way I suppose that’s positive; it isn’t wasteland any more. It was for a good few years, but now at least there’s houses on there providing homes for people.”

Roger Tiley

Roger TileyThe changes to the landscape vary widely across the former coalfields.

“Some have factory units on them, half-empty I would say. Mardy [colliery in Maerdy, Rhondda Cynon Taf] is one place where you could walk up there and unless you knew there was a colliery, you wouldn’t [be able to tell].

“There’s some concrete bases there from the buildings and there’s some tiles from the pit canteen that are still there, but youngsters wouldn’t really know that.”

Other places like Penrhiwceiber in the Cynon valley have become playing fields.

Roger Tiley

Roger TileyWhile he acknowledges the good in reusing sites, Roger laments the loss of so many jobs and the community they engendered.

“Each pit would have employed in the region of 1,000-plus men. If you multiply that by 30, 31 pits still working at the time of the strike, that’s a lot of men, and all the industries around it, suppliers etc.

“So you’re probably looking at 40,000-50,000 people employed in the south Wales coalfield, and that’s all gone.”

Roger Tiley

Roger TileyRay Lawrence, NUM lodge secretary at Celynen South for 14 years, worked as an electrician for 25 years in the mine and joined Roger as he reached the pit on his six-day walk.

“It’s hard to imagine it now,” said Ray. “I’m looking around and it’s so peaceful. But 40 years ago there was a dirty great big hole in the ground there and every morning 500 or 600 men would disappear down there.

“The place was vibrant. There was the rattle of the trams, the whirr of the winder, everything was going on, it was alive,” he said.

“There was a fence where everyone would stop and have a cigarette when they came up or before they went down. It was a real, living experience.

“Mining is a difficult thing to explain. To people outside of it, they think it’s a dirty, horrible job, which it was, but the camaraderie made up for that and it’s hard to let it go. You talk to men 40 years after and the majority of them say ‘I’d go back tomorrow if I could’.”

Roger Tiley

Roger TileyLiam Willetts is the marketing co-ordinator for Zip World Tower, a high-adrenaline activity complex on the site of the old Tower colliery near Hirwaun, Rhondda Cynon Taf, and one of the stopping points on Roger’s walk.

Tower was a rare success story post-strike, as its workforce banded together and bought it in 1994, keeping it operational until 2008 when it became the last deep coalmine in the UK to close.

Zip World opened zip lines and other attractions on the redeveloped land in 2021, but Liam said its mining past was central to the site.

Liam said: “The staff talk to all the customers, tell them the history of the site, and everyone’s really interested, especially the locals.

“It’s great to see that it’s been preserved in some sense as well. I think that was carefully thought through when building this site as a Zip World attraction.

“We’ve got some stories and newspaper cutouts that people like to look at. A huge part of the attraction is the history and the heritage.”

Roger Tiley

Roger Tiley Roper Tiley

Roper TileyThe landscapes of the coalfields have changed enormously, sometimes beyond all recognition. Nature has reclaimed many, and the environmental impact in climate terms cannot be doubted.

Roger acknowledges this: “The valleys are very green now. I live in Ystradgynlais and it’s a stunning place. There’s people from outside coming in to live, it’s a pretty, much sought-after area.

“The old coal [railway] lines are being used for people commuting to Cardiff, Newport and Bristol.

“So they’ve changed. For the better? I don’t know. I grew up in the 60s and I played on the coal tips, so that’s what I love.

“But then you walk outside and there’s these beautiful walks on the mountains and everything is green and lush. It’s a difficult argument.”