Ask anyone with a bit of knowledge about the first women’s rugby union World Cup and the myths and legends will flow readily.

It was only 31 years ago, but memories differ and rumours abound.

One team was supposedly accompanied by KGB agents. Another had to sleep on the floor of a hotel conference room three days before the final. A young baby attended talks with rugby’s international governing body as one woman balanced motherhood with organising a major tournament.

It was only nine days long, but the intrigue – as well as its game-changing legacy – has echoed down the decades since.

With the 2022 edition of the World Cup starting on Saturday, now is a good time to look back.

It all started with a meeting.

In 1990, New Zealand had hosted a festival of world rugby, although it could not be classed as a World Cup because of the small number of international sides taking part.

English players were keen for the first World Cup to be closer to home because of travel costs. The simplest solution? To host it themselves, surely.

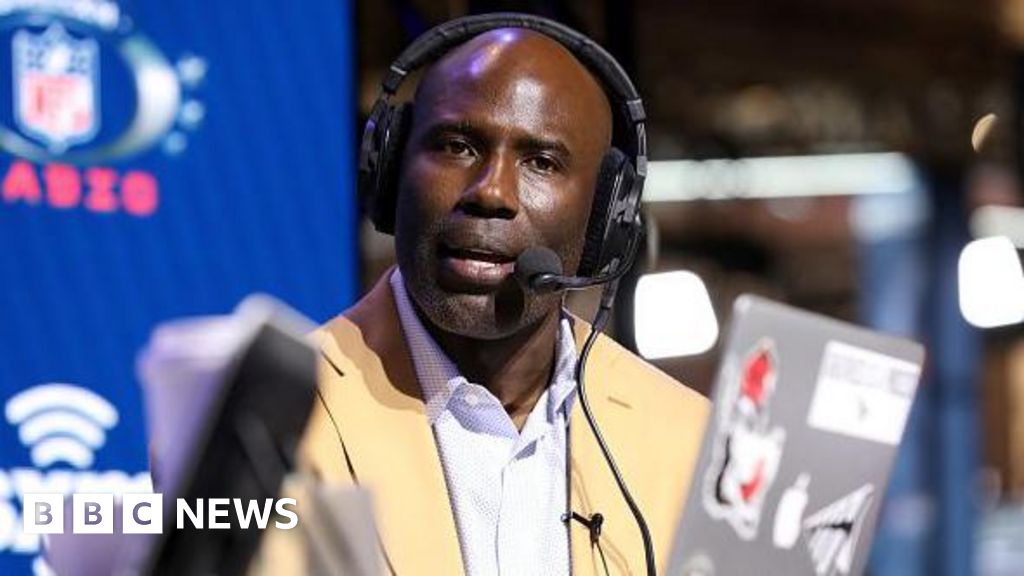

A volunteer to organise the event was sought and Deborah Griffin – now a legendary name in women’s rugby and back then already a leader in the sport – stepped forward.

The impact of that decision is still felt today, but Griffin brushes off notions of grandeur as she laughs a warm but rueful chuckle and simply recalls: “I must have put my hand up.”

Griffin chose a streamlined team of women to help. In a time before email and “before we could even patch people into calls”, it was essential that they could work together and meet easily.

So she picked her Richmond club-mates. Alice Cooper would head up the communications, Sue Dorrington led commercial affairs and Mary Forsyth was in charge of finances.

“We weren’t daunted because we didn’t really know what the problems were,” Griffin recalls of that time.

It turns out there were many.

The first was a tussle with the International Rugby Board, the global governing body for the men’s game.

Dr Lydia Furse co-curated an exhibition on the 1991 tournament that is on display at Twickenham Stadium’s World Rugby Museum until February. As part of that work, she discovered an “off the books” meeting between the IRB and Griffin.

Griffin gave birth to her first child five months before the World Cup was due to take place – a fact she mentions deep into her recollection of events as if it were a minor issue in the whole endeavour.

She was called into the IRB when they got wind of plans for the tournament and took her young daughter Victoria along.

The IRB were organising a men’s World Cup for later in 1991 and would not officially recognise the women’s equivalent. They took issue with similarities between the logos for the two events, as well as the fact Griffin’s team were calling it a Rugby World Cup.

“They were kind of told off by this international organisation,” Dr Furse explains.

“What I love about it is the strength of the organisers to walk out of that meeting and say: ‘Why on earth do they think they’re in charge of us? We’re just going to do it anyway.'”

With a possible threat of solicitors being involved, Griffin and co changed their logo but kept the name, which they felt was sufficiently different because of the inclusion of the word “Women’s”.

Griffin recalls being told by the IRB that they did not want their men’s World Cup to be impacted.

“Well how would it?” she asks now. “We couldn’t understand. I still can’t to this day think how it would in any way have impacted on their tournament.”

Dr Furse describes “apathy and disinterest in women’s rugby” at the time, contrasting with “amazing energy” from the organisers.

Back in 1991, Sunday Times journalist Paul Nelson perhaps put it best when he lamented “the regrettable sniping of men who see the game’s development as an intrusion into their territory”.

The women stood firm and set their sport on a path that would eventually lead to World Rugby – the modern iteration of the IRB – removing the words ‘men’s’ and ‘women’s’ from World Cup tournament titles in what it called “the ultimate statement in equality”, in 2019.

Griffin is 63 now and has been involved in the progression of women’s rugby almost continuously since 1978. In 2018 she became one of the World Rugby Council’s first female members.

She describes the early days of her activism as “fight, fight, fight”. The IRB was not the only challenge.

There were seemingly endless bumps in the road.

France confirmed they would take part in the World Cup – scheduled for April – just minutes before the draw took place in February.

New Zealand – called the ‘Gal Blacks’ at that time – were at the centre of a debate over whether women should perform the Haka with a wide-legged stance.

A sponsorship company had been hopeful of raising £250,000 but instead Griffin says they only got “a few things in kind”, leaving the organisers short of money.

And England’s players were flying high on the way to the final when the hotel rooms they had been offered for free were suddenly double booked.

“We’re three days from the final and we’re looking for bed and breakfasts but they allowed us to sleep in sleeping bags in the conference room, it was just a nightmare,” Dorrington told World Rugby in June.

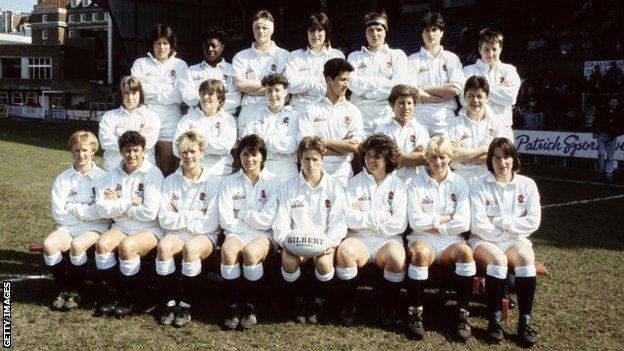

Although England’s men’s union the RFU would offer help later, the separation was such that the 1991 side wore a different rose on their shirts to the men’s team – with France and the United States having different logos too.

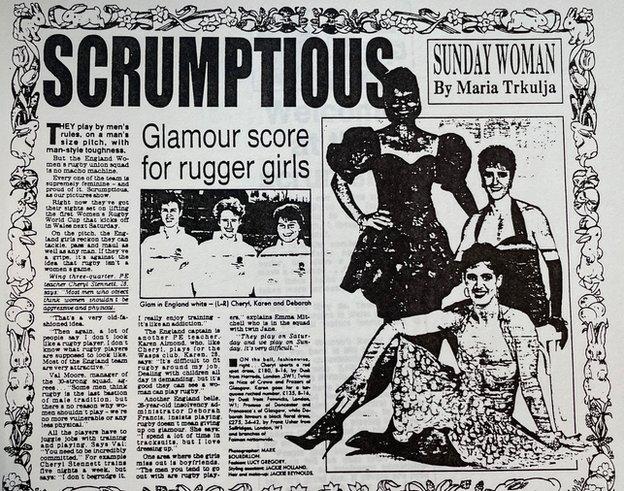

Some newspapers saw women playing rugby as a novelty. A piece in the Sunday Mirror on 31 March 1991 was headlined ‘Scrumptious’, with England players posing in evening gowns and the journalist assuring readers the team is “no macho machine” and instead “supremely feminine”.

But it is not entirely a story of misunderstanding, opposition and strife.

Cardiff was chosen as the host city because local authorities offered to pay for a welcoming ceremony and closing dinner.

Vernon Pugh, who would go on to be chairman of the IRB, convinced Welsh clubs to host matches and some male rugby writers took the games seriously.

On the pitch, the Japanese team was a highlight for many. They had never played a Test match before and did not score a single point throughout the tournament.

Instead they drew attention with their reportedly pink scrum caps worn by every player, some standing at 4ft 9in tall, and by bowing to opposition scorers every time a try was conceded.

If Japan was the most heart-warming team, the Soviet Union was the most intriguing.

There had been hints of what was to come when the Soviets attended the 1990 rugby festival in New Zealand. Suspicions were immediately confirmed when the side arrived at Heathrow.

Because of the sponsorship woes, teams were expected to provide their own transport to Cardiff and pay for accommodation and food. The Soviets could not. England player Carol Isherwood drove to their rescue.

A rumour swirling around the tournament also suggests the Soviets’ large entourage included KGB agents. Dr Furse stresses that she has not been able to verify that. But one thing that is down in print is a customs debacle surrounding the side.

Unable to leave their communist homeland with hard cash, the Soviets instead travelled with goods to trade. Apparently this ranged from caviar to Soviet champagne and it is said the side attempted to sell vodka on the steps of Cardiff’s City Hall, pushing their luck too far.

Griffin recalls being woken by customs officers at her door and having to go down to the Cardiff Institute, where the Soviet team were staying, to help smooth things over.

Customs were calmed, but tensions sprung up with other teams.

Not allowed to sell their goods, the Soviets were left with no money for food and were said to be “hoovering up all the breakfast” at the accommodation they shared with other sides.

World In Their Hands, a book about the tournament written by Martyn Thomas, quotes Soviet coach Vladimir Kobsev as saying at the time: “We have no money and nothing to eat. It is a desperate situation.

“The girls love rugby and are determined to play well but the danger is that they will be too weak to provide serious opposition. It is tragic, they have all the heart in the world and have saved everything to come to Wales.”

After those words hit the press, the people of Cardiff stepped in to help, with one cafe offering them a daily three-course meal and the local Marks & Spencer providing credit for clothes.

Griffin says: “The other teams who had also scrimped and saved to get there – most of them were spending their own money, it hadn’t been gifted to them by their unions – felt a bit put out. There was a little bit of resentment.”

Like Japan, the Soviet Union did not score a single point at the tournament.

Testimonies from Soviet players at that time have been hard to come by, but Scrum Queens writer John Birch spoke to Larisa Masalova in 2009, who said: “For most of us it was the first time we travelled abroad or even got passports. We loved that trip.”

Even with all the twists and turns – and despite Griffin’s claim that she did not sleep while the tournament was on – the final came around.

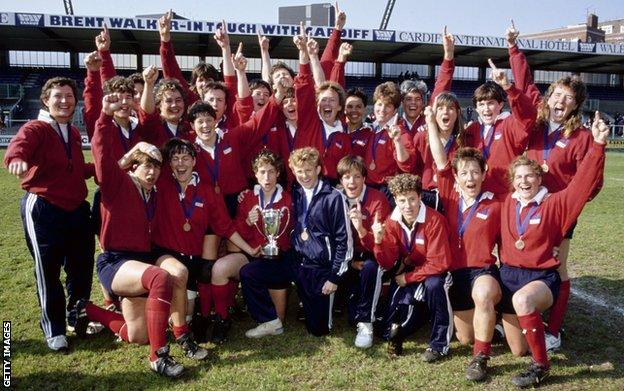

The United States, bolstered by “locks from hell” and “turbo props” beat England 19-6 in front of around 3,000 fans.

It was a celebration of what women were capable of on and off the pitch, but one that left organisers £36,000 in debt. First there was the £30,000 owed to a company that had promised big sponsorship returns – which failed to materialise. Then there was the Soviets’ accommodation.

Times rugby correspondent David Hands wrote that there was a “moral responsibility” on the men’s game to help cover the costs.

In the end the men’s RFU stepped in and told the company asking for £30,000 it would not be paid, before writing a cheque for the remaining £6,000.

This tacit support from the men’s governing body was a step in the right direction, but it was not until the turn of the millennium that the women’s union was brought into offices at Twickenham and the two organisations only merged as recently as 2012.

Now the RFU is vocal in its support and offers some of the best professional packages in the world.

Yet the journey is not over. England’s players may have full-time contracts – putting them ahead of the rest of the world – but they were still expected to fly economy to New Zealand, with current funds for women’s rugby limited.

Griffin says “nowadays there would be a mental health name” for how she felt after the 1991 tournament, adding: “I just collapsed afterwards. I hardly saw anybody for six months.”

With World Rugby firmly behind this year’s event in New Zealand, it should be a less stressful tournament. It will also provide vindication for Griffin and the other volunteers – proof that their hard work contributed to something bigger. All four of the chief organisers will be inducted into the World Rugby Hall of Fame and presented to the crowd at the Eden Park semi-finals.

Dr Furse says “it’s hard to understate the importance of 1991” in women’s rugby reaching its current stage. New Zealand’s rugby union was one of those that went from opposing the event to welcoming the sport afterwards.

The IRB would not recognise the 1994 World Cup either – held in Scotland and won by England – but did eventually take responsibility for the tournament in 1998. The names of the first two winners were finally added to the World Cup trophy in April.

Griffin says pulling off the 1991 tournament brought about “a self-belief change” for those involved.

“I think people realised we weren’t going to go away,” she says. “It was a case of: ‘We’re not alone.'”

They were definitely not alone: around 3,000 fans attended the 1991 final. With more than 30,000 tickets sold for Saturday’s opening match day in Auckland, it is hoped the city’s 60,000-seater Eden Park will be full for the tournament decider.

Much has changed since 1991, and Griffin is one of many hoping for more to come in the next three decades.