Amusingly, given she was on the other side of the world when the episode played out, it is Jade Clarke who brings up the subject of the fridge.

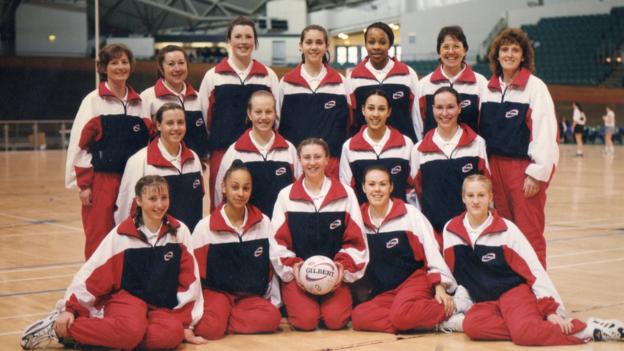

On the eve of their record-equalling sixth Netball World Cup, Clarke and Geva Mentor – England’s two most-capped players – are reminiscing about how it all began; a dual journey they started together for England Under-17s more than two decades ago and poised to end imminently.

It was in 2001 that Mentor, then just 16, was called up to the senior England squad for the first time to take on New Zealand on foreign soil. The Silver Ferns would seal a 3-0 series whitewash on the court, but debutant Mentor was to claim a longer-lasting prize off it.

“It was quite funny,” she recalls. “In New Zealand, [appliance manufacturer] Fisher & Paykel were the main sponsors.

“After the last game they organised a competition where both teams had to shoot a ball into an open washing machine – one you filled from the top. Everyone, players and staff from England and the Silver Ferns, stood on the line and had a go.

“Old goal keeper over here, who can’t hit a post to save her life, managed to get the first round in and then again in the second round. Eventually, I was up against the physio from the Silver Ferns. I got one in and she missed again so I won – and the prize was a fridge!

“They were asking me whether I wanted it to open on the left side or right side. I was only 16 so had no idea and was on the phone to my mum asking her.”

More than 22 years later, the stainless steel appliance still sits on the upstairs landing of Mentor’s mother’s house in Bournemouth.

The legacy of the country’s two most experienced international netballers stretches far beyond a two-decade-old appliance on the south coast.

As England prepare their bid for World Cup glory, few players can claim to have impacted the national side more than Clarke, 39, and Mentor, 38.

Both played key roles in the Roses’ ground-breaking 2018 Commonwealth Games triumph that propelled the sport onto the front pages and into the public consciousness.

So sparse was netball coverage when the pair started out that Clarke was unable to even watch a single England match until the 2002 Commonwealth Games, just a few months before her own international debut.

“When we were growing up it just wasn’t in the media,” she adds. “It’s been such a huge shift.

“Back then, our domestic league was just watched by our family and friends. I had no way of watching England. I had an older sister so I’d watch her play and I’d watch the county seniors – players like Tracey Neville and Karen Greig played at Greater Manchester, so I’d aspire to be like them.

“But even though I couldn’t see it, I always dreamt of playing for England. I wouldn’t have thought back then that the sport would get to where it has done.”

Things have changed beyond recognition. In South Africa over the next fortnight, the England squad will have access to the type of video analysis, data science and advanced training theories befitting their status as one of the best teams in world netball.

Yet far from the professional set-up enjoyed by today’s full-time and centrally-contracted players, Mentor and Clarke were raised on a more rudimentary operation.

“We used to meet every other weekend, but would hardly have any time together to get everything done,” says centre Clarke, whose 200 England caps are a world record for a single country.

“Now it’s a full-time programme, so we meet Monday to Thursday every week.

“The coaches used to do pretty much everything, but now we have a nutritionist, psychologist and so much more support all around.”

Given the close-knit nature of the sport, the pair have become accustomed to navigating changing relationships over the course of their careers.

While team-mates have come and gone, others have become superiors.

At those 2002 Commonwealth Games in Manchester, a teenage Mentor shared a room with Jess Thirlby, who is now in her fourth year as England head coach.

“We’ve also got Sonia [Mkoloma], who is one of my best mates, as our assistant coach, and Olivia Murphy, who was our technical coach, was my first England captain,” says Mentor, who has played 167 times for her country.

“The beauty of it is we see everyone as people first and then those roles second. You’ve got the foundations in place in terms of those friendships and from that you can build the respect around the roles that they play in netball. We are all fortunate enough that we get on really well.

“We’ve all been in teams before where we’ve been young and you have a coach that is a lot older – like being a kid at school with a mother figure. Now we’re older than some of the staff.”

That has potential to cause problems for players like Thirlby, who was a peer for most of Mentor and Clarke’s careers, and now leads the team despite lacking her former team-mates’ depth of playing experience.

Nonetheless, Thirlby remains in awe of two players who have continued to defy age and withstand the intensifying rigours of a sport that has become increasingly professional.

“My overarching feeling is how bloody lucky are we to have two of the oldest, smartest, most knowledgeable players still playing at this level?” she says. “It’s incredible.

“I was around Geva when she first came to a session at Team Bath and she was a gangly 15-year-old who tripped most of us up in training. It is incredible for those like me to have been a senior player when she broke onto the scene and now we’re in a whole other lifetime, but she’s still playing.

“They are both fantastic role models and we’re so fortunate they have stayed in the game this long. They look good though, right? They are like fine wines, getting better with age.”

For any player involved in English netball over the past decade there is an undeniable sense of two distinct eras: one pre-2018 and another post-2018.

When Helen Housby sunk her buzzer-beater in the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games final five years ago, she not only sealed victory over the all-conquering Australians, but changed the sport in an instant.

For England, who had never previously won a major competition, it proved they could compete with the dominant southern hemisphere nations.

“Before that, the other teams were put on a bit of a pedestal,” admits Mentor.

Of wider significance was the impact it had on the game as a whole. From something of a niche sport, associated for many with their schooldays, netball entered the mainstream.

“I didn’t know about the England set-up until I got invited for an England trial,” says Mentor. “I knew there was a national side, but I didn’t know what their nickname was or who represented them.

“It’s so great now to see more high-profile teams on TV, being able to follow the Super League, and being able to watch games overseas.

“For us, as an England side, seeing the shift in the number of people in the crowd and following along on TV, it’s really shown where England places netball as a sport.

“We didn’t have the inspiration of seeing a national side, but now we hope we are role models for girls and boys coming through and wanting to play netball.”

Earlier this summer, Mentor – who will join Super League side Leeds Rhinos next season after 16 years playing domestically in Australia – confirmed she would retire from the international game after the World Cup.

The tournament also looks likely to be Clarke’s final outing in a red England dress after she was omitted from next year’s central contract list, with Thirlby instead opting to concentrate on a younger cohort for the next four-year cycle.

But, unlike Mentor, Clarke insists she will never formally retire.

“I remember David Beckham never retiring and thought I’d always do that,” she says. “I’ll always be available if they call on me, but I’m not expecting the call.”

With the end nigh, the World Cup presents the perfect opportunity for a dream farewell. Tasked by Thirlby with “going where no Roses team has been before”, third-ranked England are hoping to make their first final in the competition.

They underperformed at last year’s Birmingham Commonwealth Games, losing to New Zealand in the bronze-medal match as Australia beat Jamaica to gold. That trio of rivals will again provide the sternest opposition if Mentor and Clarke are to add gold or silver to their three bronzes from the last three World Cups.

“We’ve been to so many World Cups, but we’ve never broken into that final,” says Clarke. “So, even though we’ve been around for so long, that’s still a first that we want to achieve. That really excites us. The final would be the dream – it would be incredible. Every day when it gets tough in training, that’s what you’re doing it for.”

Not that Clarke could ever have envisaged being in such a position more than two decades ago.

Back in 2002, as a wide-eyed teenager, she was handed an envelope at the conclusion of her England trial. Inside was a letter that would determine her fate of whether she had been selected to pull on the national team’s dress.

“I still remember it so vividly,” recalls Clarke. “My mum was with me. We ran outside, read the letter and we were just screaming. To get into the squad was so big. I got to live out my dream.”

If she bows out with a World Cup winners’ medal, there will be plenty more screams.