Madeleine Pape weaved her way patiently through a crowded room in Botswana’s Gaborone Conference Centre.

She was determined to catch up with Caster Semenya, the celebrated – and controversial – South African athlete who had once been Pape’s rival.

The Australian wanted to make amends with the women’s 800m triple world champion and double Olympic gold winner, who was the star of an international conference in the African country in May 2018.

“I finally was able to approach her,” Pape tells the BBC.

“I told Semenya how much I respected her and enjoyed seeing her compete.”

This was not how Pape felt the only other time the two women met, in 2009. Back then, she had thought that Semenya did not even belong on the same track as her.

The Berlin controversy

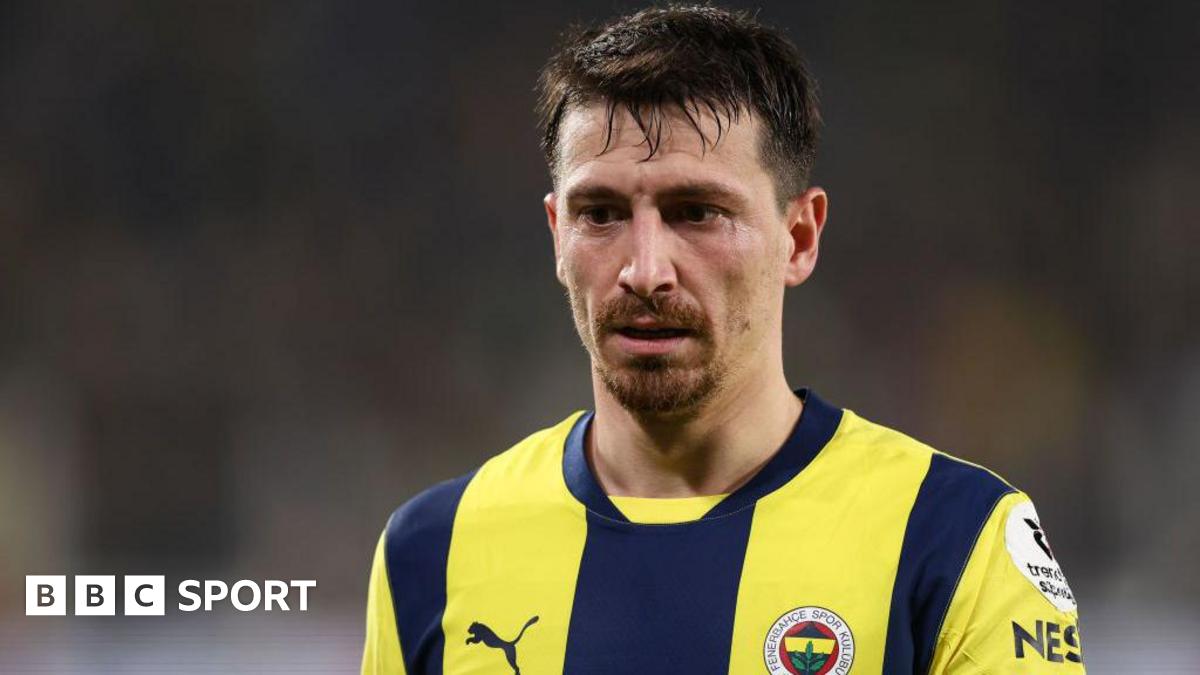

In August 2009, the Australian was one of the runners who lined up alongside Caster Semenya in an 800m heat at the the World Athletics Championships in Berlin.

It was one of the first times Semenya had ever raced outside Africa, but she was already under intense scrutiny.

At 18, the South African had won a junior tournament earlier that year with a time that was only marginally slower than that of more established 800m competitors, such as the 2004 Olympic Champion Kelly Holmes.

Semenya had also managed to shave seconds off her 800m personal best in the space of only nine months.

But those criticising the runner were not accusing her of using banned substances.

Instead, she was “guilty” of being too fast for a woman. Her gender was being questioned.

In the words of Michael Seme, Semenya’s coach at the time, she “looked like a man”.

Many in the world of athletics had reservations about her participation in the World Championships. Madeleine Pape was among them.

“At that time I did think it was unfair for her to compete against the rest of us,” she recalls.

Even the governing body for athletics (IAAF, now rebranded as World Athletics) had expressed doubts about Semenya’s biological sex during the World Championships – news that it had requested a gender verification test leaked to the world’s media just a few hours before the 800m final.

“It was by far the easier option for me to join the chorus of voices condemning her performance,” Pape adds.

“It was just convenient to go along with what most of my colleagues and coaches were saying.”

Once against the idea of Semenya even stepping on a running track, the Australian is nowadays a vocal supporter of the South African’s fight to compete.

What made her change her mind?

Different tracks

Madeleine Pape didn’t have a good run at all at the World Championships.

She finished next to last among seven runners and failed to qualify for the next round.

Semenya, on the other hand, won the heat and never looked back, winning the gold medal in Berlin by crossing the finish line more than two seconds clear of the other runners in the final race.

It was such an impressive margin of victory that one of the competitors in the final, Italy’s Elisa Cusma, accused Semenya of “being a man”.

Pape’s career would end with an injury in 2010. She then pursued an academic career, with a PhD in Sociology and studies on gender issues in sport.

It is as an academic, rather than as a former athlete, that the 36-year-old Australian mostly comes up in internet searches.

In the classroom, Pape saw what she had never recognised on the track.

Difference of sex development

Semenya, now 29, has hyperandrogenism – a genetic condition that makes her body produce higher levels of testosterone.

Testosterone is a hormone that most women have in much smaller amounts than men, and is associated with stronger performance in sports.

In its artificial form, testosterone is part of the World Anti-Doping Agency’s list of banned substances.

Semenya’s condition results from what is known as difference of sex development (DSD).

People with a DSD do not develop along typical gender lines.

Their hormones, genes, and reproductive organs may share a mix of male and female characteristics.

Many in athletics argue that hyperandrogenism offers Semenya an unfair advantage on the track.

Pape used to be among them.

“My views changed when I went to university and had access not only to different perspectives but also to the science behind the arguments that were used against Semenya,” says the Australian.

Run on the track, fight off it

The results of Semenya’s gender verification tests have never been made public and she continued to compete in international events such as the Olympics.

However, World Athletics last year issued a new ruling that forces Semenya and other athletes with hyperandrogenism to take testosterone-reducing drugs in order to be eligible to compete in women’s events between 400m and a mile (1,609m).

The South African challenged the ruling but has lost an appeal in the Court for Arbitration of Sport.

A further legal challenge in the Swiss Federal Supreme Court was dismissed on 8 September this year.

Semenya refuses to take the drugs, arguing that it could endanger her health and that the ruling denies her and other DSD athletes the right to rely on their natural abilities.

As things stand, the South African will not be allowed to defend her 800m title in the Tokyo Olympics next year unless she accepts the drugs, whose effects will almost certainly slow her down.

The fairness argument

For Pape, the stance of World Athletics is harmful to the sport.

“Their agenda so far has been to look for ways to exclude some women,” she says.

“They are missing the ability to listen to these women and to relate to what they are going through.”

Semenya is not the only high-profile case of DSD in athletics.

In the 2016 Rio Olympics, the 800m silver and bronze medal winners were Burundi’s Francine Niyonsaba and Kenya’s Margaret Wambui, who also have hyperandrogenism.

In a statement issued on 8 September, World Athletics stood by the argument that it was pursuing fairness.

“For the last five years, World Athletics has fought for and defended equal rights and opportunities for all women and girls in our sport today and in the future,” the statement read.

“We therefore welcome today’s decision by the Swiss Federal Tribunal to uphold our DSD regulations as a legitimate and proportionate means of protecting the right of all female athletes to participate in our sport on fair and meaningful terms.”

“She’s an exceptional athlete”

Pape, however, sees it differently.

“The system has stacked the odds against Semenya from the beginning,” Pape says.

If in 2009 the Australian thought her rival had an unfair advantage, her views could not be more different now.

“Semenya is an exceptional athlete. Anyone who has won all those medals has got to have something that sets her apart,” she says.

“I don’t think that it is testosterone.”

Is testosterone really so significant?

The link between testosterone and higher performance is controversial among sport scientists.

Julian Savulescu, a professor in Biomedical Ethics at Oxford University, told the BBC that the science behind World Athletics’ arguments is “inadequate”.

He refers specifically to the 2017 study commissioned by the governing body, which claimed that high testosterone was responsible for as much as 3% improvement in runners’ performances.

“It is a single study, conducted by World Athletics, and the full data have not been released for independent replication,” Savulescu explains.

“Semenya has been singled out above any other athlete. I don’t know why that is.”

Supporters of Semenya have often expressed the view she is the victim of prejudice.

The South African athlete is openly gay, and married to another runner, Violet Raseboya.

In July this year, the couple announced the arrival of a baby girl.

Madeleine Pape thinks Semenya’s fans have a strong point.

She argues that other women athletes who dominate the sport in a more emphatic way than Semenya do not get the same scrutiny. She uses the American swimmer Katie Ledecky, owner of a large collection of medals and world records, as an example.

“Semenya is no more exceptional than Ledecky, but Ledecky’s gender has not been openly questioned,” Pape observes.

“But Semenya is a black South African woman who isn’t straight and acts a bit like a tomboy. She doesn’t conform and expresses her identity in her own ways.”

“So, the problem here clearly doesn’t seem to be based on her performances,” she adds.

Indeed, Semenya has not always crossed the finish line in first place.

The South African failed to win the 800m both in the 2011 World Championships and the 2012 London Olympics – she was only awarded the gold medals retrospectively in 2017, after the original winner, Russia’s Mariya Savinova, was disqualified for doping.

Making peace with the past

In that conference in Botswana, Madeleine Pape was not sure if Semenya would remember the only time they had met.

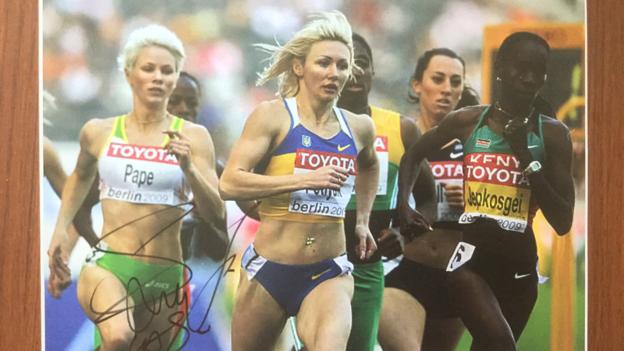

So, the Australian sociologist carried a picture of them together.

It was a snapshot of that 800m heat in 2009.

In the picture, Pape is running alongside other competitors. Semenya is partially “hidden” behind Ukraine’s Tetiana Petlyuk and Kenya’s Janeth Jepkosgei.

It’s an image that Pape still treasures, but with a much-valued addition: Caster Semenya’s autograph.