Jayne Mitchell turned the key and pushed open the door.

“There was a small single bed, a weird thing in the bathroom that seemed like a mix of shower and bath, and this dodgy wallpaper, grease patches all over it, that looked about 100 years old,” she remembers.

Three weeks before, on 28 July 1984, a man on a jet pack had flown into the Los Angeles Coliseum to open the city’s Olympics. But in a divided era, Mitchell was on the other side.

Instead of Los Angeles, she was in Prague. Instead of the athletes village, she was in a low-rise hotel. And instead of the Olympics, she was at the Friendship Games.

They were an alternative Games for a different world view. After the United States and a clutch of its allies had stayed away from the Moscow Olympics in 1980, the Soviet Union and its allies retaliated with their own boycott four years later.

Pravda, the Soviet state newspaper, said the Friendship Games, organised by the USSR and its satellite states, would show “that Socialist society provides more favourable facilities for the human beings’ all-round physical and spiritual development”.

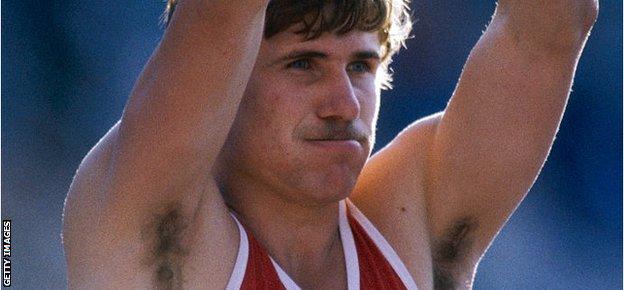

Sergey Bubka, the fresh-faced 20-year-old Soviet pole vault world holder, went further.

”It is a pity that the Olympic flame in Los Angeles was darkened by the spirit of profit-making,” he was quoted as saying by the Soviet Union’s official press agency.

“The atmosphere of anti-Soviet and anti-socialist hysteria in the USA prevented athletes from most Socialist countries from participating in the Olympic Games.

“We hope that ‘friendship’ competitions will show to the world at large anew the strength of athletes from socialist countries and their loyalty to the Olympic ideals.”

Mitchell, then aged 21 and competing under her maiden name of Andrews, had little knowledge of what she and the four-strong British team of female athletes were getting into.

And, more pressingly, as she stood surveying her sparse hotel room, she had no luggage.

The Friendship Games had its own opening ceremony. One with fewer jet packs and more political messages.

In Moscow’s Lenin Stadium, about 100,000 spectators, including future leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the VIP seats, watched troupes of dancers go through precisely choreographed routines.

Banners were unfurled exhorting the ‘health of the people’ and the place of sport in the Communist government’s latest five-year plan.

Finally, there was a song. Specially composed for the event, it included the lyrics: “To a sunny peace, yes, yes, yes, to a nuclear war, no, no, no.”

As Mitchell and her team-mates had gathered together on the tarmac at Heathrow, they’d thought they were heading to a regular continental meet.

Joyce Hepher was a long jumper. She had gained the distance to qualify for Los Angeles – but only two days after the British team had already been submitted to the International Olympic Committee. There was no way of adding her. So, instead she was boarding a plane to Prague, where the women’s athletics events for the Friendship Games would be held.

In all, nine countries served as hosts. The table tennis was in North Korea, the boxing in Cuba.

“I only heard about it a week before we are about to travel,” Hepher, then competing under her maiden name of Oladapo, tells BBC Sport.

“I had no idea about the magnitude of it all. I initially thought it was a Grand Prix type meeting and it was only when we arrived at the hotel and saw all of the other athletes. Literally anyone who was anyone in the Eastern Bloc was there.”

In the lobby were East Germany’s Marlies Gohr and the Soviet Union’s Lyudmila Kondratyeva, the world and Olympic 100m champions respectively. East Germany’s Marita Koch, whose 1985 400m world record still stands today, was there. As was Czech Jarmila Kratochvilova, whose 800m mark from 1983 also remains unsurpassed.

Hepher looked down her own startlist in the long jump. Nineteen-year-old world champion Heike Drechsler was joined by Russian Galina Chistyakova, another whose world record from the era still endures.

“The qualifying round was quite intense,” Hepher says. “I remember waking up really early to warm up and when we got to the stadium, they had all this high-tech equipment on the runway that measured your speed coming to the board.

“I certainly hadn’t come across that in any other competition.”

The final was won by Drechsler with a leap of 7.15m. The top four at the Friendship Games all produced jumps greater than the one that had won gold in Los Angeles earlier in the summer.

“It was definitely a stronger competition than in the Olympics,” Hepher adds. “The first three got well over seven metres; it was a very competitive and very strong field.”

Mitchell’s 100m event was similarly stacked. Gohr took gold in a faster time than American Evelyn Ashford had run for the Olympic title. Alice Brown, who won silver behind Ashford in Los Angeles, finished down in fifth, as the sole US track competitor.

But times and distances from the era came with questions. In the years since, the Iron Curtain has rolled back to reveal the work of state-sponsored doping regimes, even if many of its results still stand.

“Those rumours were always there,” remembers Hepher. “Things about Eastern Bloc athletes and their programmes and ‘vitamins’. But until anyone was caught, no-one could really say whether they were drug takers or not.”

Mitchell adds: “It was hard times for them as well. It wasn’t really their fault ;they were plucked from society as talented athletes and offered a better life for them and their families. It would be hard not to follow the regime in those countries.”

The performances, in-stadium technology and out-of-competition pharmaceuticals might have been world-leading. But life away from the track, on the street, was not.

After her luggage failed to follow her from Heathrow to Prague, Mitchell went to find supplies.

“I went to a series of local shops and in each there was a glass counter with one of everything on display – a toothbrush, toiletries, some clothes,” she says. “You would point to what you would want.

“The underpants came in a pack of seven, with different days of the week written on them.

“There was a lot of poverty. We were given some canned drinks at some point and kids were clamouring around us because they wanted this can of Coke. It was really special to them to have something that, to us, was so ordinary.”

Eventually Mitchell’s luggage – complete with the cans of beans and portable stove that she’d packed – arrived just in time for her return to London.

When they landed, there was no reception or ovation. In fact, there was little recognition of the Friendship Games at all.

There had been no coverage on television. There were no reports in the newspapers. With no British athletes taking part in the men’s athletics events, Mitchell believes she and her team-mates were on the wrong side of the gender, as well as political, divide.

“In that era, male and female athletes in the same team were treated differently,” she says.

“We were just not considered as important. We would get expenses by going up to a table and getting an envelope. Some of the other athletes went to a better table to get their expenses. There was a ‘jobs for the boys’ culture.”

But what they got back from the Friendship Games couldn’t be counted in pounds.

Neither Mitchell nor Hepher ever went to an Olympics. For them, a forgotten corner of track history remains a high point.

“It’s not recognised, even within the athletics community, as being what it was,” says Hepher.

“It hasn’t got the same sort of kudos as the Olympics. But looking back now, even if at the time I didn’t realise the magnitude, I feel honoured to be part of it.

“I look back on it as my Olympics.”