Naseem Hamed could not somersault over the top rope this time.

The trademark ring entrance of the self-styled ‘Prince’ was off limits as his gloves were unable to grip the ring ropes.

It pointed to the misery that would soon unfold. Extreme weight loss, arguments and botched training preceded his 2001 bout with Marco Antonio Barrera. This was a fight where nothing went right.

The weight and the carrot

Team Hamed set up in Palm Springs, California – in the former home of singer Bing Crosby – for a training camp that would lead to his first Las Vegas bout, nine years on from his debut at Mansfield Leisure Centre.

Mexico’s Barrera was working out at at altitude but Hamed started camp needing to lose 35lbs to make 9st. A broken hand had led to rest and weight gain.

Lead trainer Emanuel Steward was absent for all but the final weeks of camp, reporters including 5 Live Boxing’s Steve Bunce were hearing whispers of “disastrous” preparation and those closest to Hamed maintain to this day that he should never have entered the ring.

“I boiled myself down to make weight,” Hamed says. “I got to Vegas and was wearing sweat suits. I was in my room at 5am still on a treadmill and having the hottest baths I could. There was a point where I was in bed and couldn’t even pick up my head.

“I should never have taken that fight. It’s that carrot that dangles in front of you with so much money.”

The disaster begins

About $6m ($4.9m) was pushed the way of Hamed, whose standing even led to him dancing with Michael Jackson prior to his US debut years earlier.

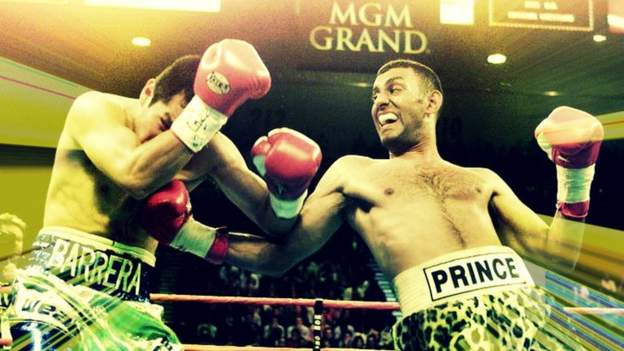

Some 28 of 30 reporters polled picked Sheffield’s box of tricks for victory on a night where he was supposed to “cement his greatness” according to 5 Live’s Mike Costello.

Delayed on his ring walk by an enforced glove change, Hamed was then soaked with beer by a fan and abandoned his trademark somersault as his new gloves were not cut correctly. Fans booed when he turned down the acrobatics.

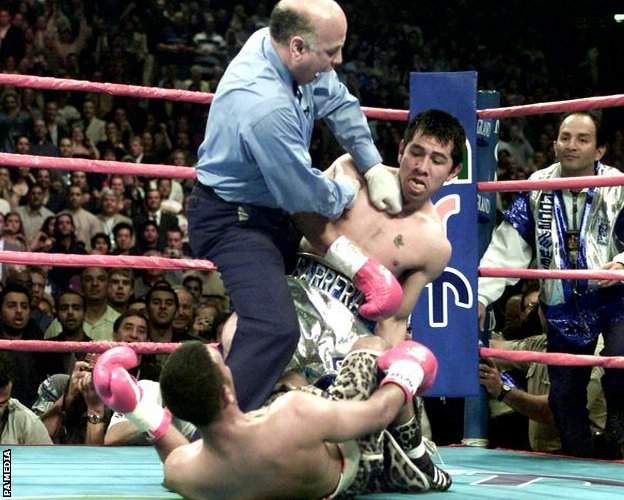

A left hook stuns Hamed in round one and in the second he desperately wrestles Barrera to the canvas. When the pair regained their feet it was Hamed – typically so ruthless – who sought to show respect by offering to touch gloves.

“It showed me psychologically he wasn’t getting his own way,” says former world champion Carl Froch, who was in Las Vegas as a fan.

Bunce added: “This is an unmitigated disaster. We are watching a fighter being ruined by an utter lack of preparation.”

The grip of stardom

Four years earlier Hamed had become the first British fighter in a decade to hold two world belts at one weight.

Brendan Ingle, who had trained him from childhood, had been jettisoned in a war over pay. Life around this flashy fighter in a gritty business was changing.

A week before facing Barrera, Hamed demanded to speak to bosses at the MGM Grand to ask why he would not get the presidential suite. The 6,500 square foot room he ended up with – complete with pool table, bar and steam room – had to make do.

Less than 24 hours before the bout he flew his barber in from Los Angeles to get a haircut. He even moved to fly someone to Mexico to ensure his gloves were made from goat skin. “They’re the best to taste when their smashed in your mouth,” Hamed would remark.

Then there was the energy-sapping chaos. Both camps argued over who wore green gloves and who wore yellow. No one agreed so both wore red. Both argued over the length of ring walks. Team Barrera were not backing down in the face of a star’s demands.

The cruel end

Barrera – brilliant from start to finish – had room to have a point deducted late on for thrusting his soon-to-be-beaten rival into a ring post.

“One day we will get the truth which I’m convinced is somewhere around ‘I just wanted to get out of the ring and didn’t want to be there,'” Bunce says when reflecting on Hamed’s unanimous points defeat.

In the changing rooms Lennox Lewis tells Hamed’s family that the greats come back from defeat. Two weeks later he would lose his world heavyweight titles to Hasim Rahman, only to win them back in a rematch.

Hamed, though, returned for just one fight and retired aged 28. Two decades of punching – including 18 world title fights – had left his hands in ruins.

“He changed boxing in Britain,” Bunce says. “He dragged people along. I’ve never known a career be so defined by one night and it be so joyously celebrated.”

Froch replies: “It can be so cruel, you can get defined by one loss. It saddens me but that is boxing. It is brutal.”

The late Ingle once called a young Hamed “a cocky little thing”.

Some unquestionably cherished the night a swaggering superstar was undone.

Hamed might forever wonder what may have been, had he been truly ready.