For a team that would enter football history as The Immortals, it was a chilling reminder of the frailty of human life.

On 10 November 1988, Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan faced Red Star Belgrade at their Marakana Stadium in the European Cup second round, second leg. The match – replayed from the previous day after an abandonment due to fog – took a horrifying turn just before half-time.

The score was 1-1 – and 2-2 on aggregate – when Red Star defender Goran Vasilijevic clashed with Milan’s Roberto Donadoni.

Sacchi, in his newly published memoir The Immortals, describes the incident.

“Vasilijevic went in violently on Donadoni, hitting him with a head butt and an elbow at the same time,” writes the Italian coach.

“Roberto hit the deck, knocked out. These were moments of true terror: he looked dead. Players were waving their arms about and putting their hands on their heads.”

As Donadoni lay prone, Angelo Pagani, the Milan masseur, was first to reach him. He managed to open the player’s mouth – jammed shut due to a fractured jaw – and free his tongue, which had been forced to the back of his mouth and threatened to choke him.

Milan doctor Ginko Monti, next on the scene, administered mouth-to-mouth. “Roberto showed no sign of life, and then he began to stamp his feet on the ground, which often happens to people who have suffered cranial trauma,” writes Sacchi.

Donadoni’s team-mates looked on in horror. Legendary Milan and Italy defender Paolo Maldini recalled the fateful moment: “He was blue, with his eyes wide open, and he was stamping his feet like an animal in the slaughterhouse.”

Marco van Basten, the team’s iconic Dutch striker, ran to the Milan bench shouting “A doctor! A doctor!” before seeking comfort in the arms of general manager Paolo Taveggia and bursting into tears. Van Basten did not want to play on but the Milan coaching team convinced him to, as Donadoni was carried off on a stretcher and rushed to hospital.

A shell-shocked Milan returned to the dressing room at half-time. Then they heard an announcement over the public address system which was roundly booed by the home crowd. When the same announcement was made in Italian, they understood.

Sacchi explains: “The announcer had wanted to reassure fans who had seen Donadoni lying on the turf for so long without moving, by telling them the good news coming from the hospital. Roberto had regained consciousness and, apart from that fractured jaw, no serious damage appeared to have been done. The Red Star fans were booing his good health.”

Milan’s players, including Ruud Gullit, were furious. Gullit had replaced his stricken team-mate and was struggling so badly with a left thigh injury that he was only due to play 45 minutes. In the end, he played all the second half plus extra time and penalties. Sacchi describes the Dutchman as “our courage, our general in battle”. A battle it was.

With hostility pouring from the stands, Milan kept attacking. Their captain Franco Baresi transmitted calm and belief as they searched for a winner. “Every time he came out with the ball at his feet, the flames of hell made way,” writes Sacchi. But an exhausted Milan could not score again and, with an aggregate score of 2-2, the tie went to penalties.

Stojkovic converted Red Star’s first and Baresi replied for Milan. Robert Prosinecki scored the home side’s second. Then Van Basten stepped up.

Sacchi: “Van Basten moved towards the ball with that swan-like elegance. He barely touched it but it flew – hard and unsaveable – into the top-right corner. Perfect execution. I had the sense that the whole Marakana had been frozen by this exhibition of confidence and technique.”

That conversion was perhaps the decisive moment of the shootout. Dejan Savicevic followed up for the home side with a limp effort that was saved by the legs of goalkeeper Giovanni Galli before Chicco Evani made it 3-2 to Milan. When Mitar Mrkela then missed for Red Star, Frank Rijkaard stepped forward with the chance to put the Italian side into the quarter-finals of the European Cup. Sacchi turned his back, unable to watch.

“Through the absolute silence of the Marakana, I heard the dull thud of the ball striking a post,” he recalls. “The blood froze in my veins. But after hitting the woodwork, the ball rolled into the net. I’ve never forgotten the sound of that post – a hymn to happiness.

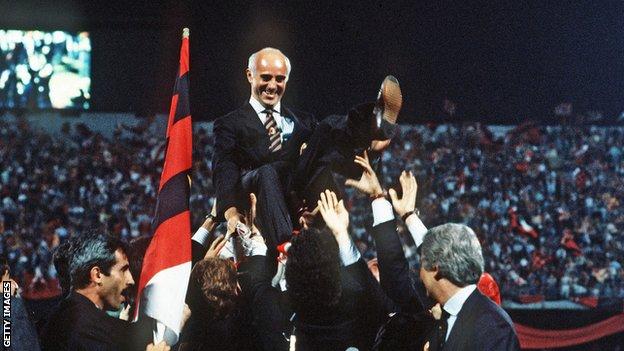

“I ran on to the pitch and hugged each of my players in turn. We had beaten Red Star, but also suffered injustice, violence, provocation. They’d spat in our faces, a policeman had set his wolfhound on Alessandro Costacurta. And yet we’d been stronger than everything and everyone.”

However, the Milan players’ joy was tempered by their team-mate’s brush with death. In a later interview with Gazzetta dello Sport, Donadoni recalled the scene at the hospital.

“The first clear image I have is waking up in the room of the hospital,” he said. “With me there were two gentlemen: one was terminally ill and kept asking me how I was, the other had fallen three storeys. He didn’t have a bone in place, but he peeled mandarins and squeezed the juice over my lips because I couldn’t open my mouth. They were in a much more serious condition but were worried about me as if I were the most in need: what a wonderful way to explain how lucky I had been.

“The thing that struck me most in reviewing the images of the incident was the reaction of my companions, who were visibly frightened and worried. They immediately realised the gravity of the moment. From these things you can see the great sense of belonging and friendship that binds you to your team-mates.”

Some of the bitterness Milan felt over their treatment in Belgrade was assuaged when both Red Star manager Branko Stankovic and Vasilijevic visited Donadoni in hospital. Milan’s flamboyant chairman Silvio Berlusconi gifted the player an expensive painting after his ordeal, but it is Sacchi who paints the most vivid portrait.

“Roberto always gave the absolute maximum in every minute of the match or training session,” he writes. “He gave the best possible interpretation of my concept of hard work and sense of duty. For this reason, his team-mates called him ‘Bone’. He never gave in.

“He was a hero. Not because he ended up in hospital. He was a hero in the manner defined by Romain Rolland – the French writer who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915. ‘A hero is someone who does what he can.’

“I agree with this sentiment, and using it, I can say that I coached a team of heroes who then became Immortal.”

After beating Red Star, Sacchi’s team never looked back. They scored 11 goals and conceded just once against their following three European opponents that season. Werder Bremen were beaten in the quarters and Real Madrid in the semi-finals before a 4-0 thrashing of Steaua Bucharest in the final. And they repeated their European Cup title triumph the following year, a 1-0 victory over Benfica in 1990 enshrining their legend.

As that one night in Belgrade proved, however, Milan’s ‘Immortals’ tag spoke as much to their bravery in extreme adversity as it did to the beauty of their football.