The scene at Kabul airport was one of chaos and desperation. Amid gunfire, people were stampeding in total panic. Thousands were trying to escape the Taliban, and Fati was among them.

Fati is a goalkeeper who honed her fluent English by watching TV series and films growing up in another, very different Afghanistan. Her full name and age are withheld to protect the identity of her family.

As the Taliban rapidly retook control of her country in August 2021, Fati quickly decided that she and her international team-mates would have to leave their homeland and loved ones behind.

For years they had played together, a football team that represented an Afghanistan of greater opportunity and freedom for women. Now thoughts turned to the public executions and stifled liberty that had been hallmarks of the Taliban’s previous rule from 1996 to 2001.

Fati had considered the Taliban’s return impossible. Her disbelief soon turned into a sense of hopelessness and dread. She had to get out.

“I accepted that Afghanistan was over,” she says.

“I thought there’s no chance for living, no chance for me to go outside again and fight for my rights. No school, no media, no athletes, nothing. We were like dead bodies in our homes.

“For two weeks I never slept. I was 24 hours with my phone, trying to reach out to someone, anybody for help. All day and all night, awake, texting and searching social media.”

Fati and her team-mates did find a way out. They were assisted by an invisible international network of women guiding their steps towards safety.

This is the story of their escape.

It starts 12,700km away in Houston, Texas, where a 37-year-old former United States marine was planning the evacuation.

“It was like a little virtual operation centre running out of WhatsApp,” says Haley Carter. “Never underestimate the power of women with smartphones.”

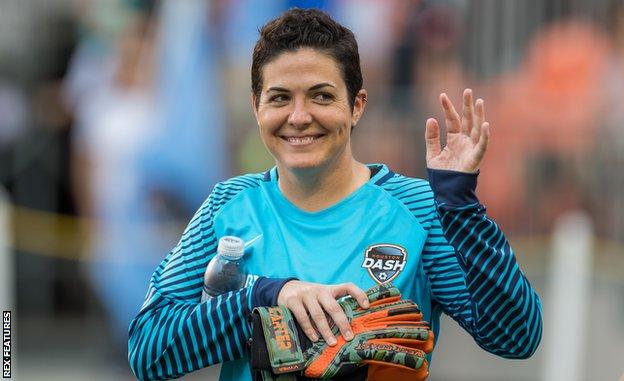

Carter, 37, was a goalkeeper too. After her time in the military, which involved service in Iraq, she played three seasons with NWSL side Houston Dash before moving into coaching. Between 2016 and 2018 she was Afghanistan’s assistant coach.

The American may have been thousands of miles away but she was sharing intelligence about the rapidly changing situation in Kabul with marines and National Security staff via encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp and Signal. The operation was dubbed a ‘Digital Dunkirk’.

“In a normal combat environment, that kind of information wouldn’t be shared. But this was an evacuation,” Carter says.

“I’ll be honest with you, I didn’t think it would be possible. It was crazy. It was wild, looking back on it.”

Carter had been enlisted to help by Khalida Popal, a former captain of her national team who had been involved in Afghanistan women’s football for years.

As a teenager under Taliban rule, Popal and her friends would play matches in total silence so the Taliban wouldn’t hear them. She left Afghanistan because of death threats over her involvement in the game and since 2011 had been living in Denmark.

Time was of the essence. Popal knew that Fati and her team-mates would be vulnerable to Taliban investigations because of their sporting exploits. She also knew that soldiers were going door to door. Many female athletes in Kabul were in hiding. Many feared for their lives.

She told Fati and the other players to delete their social media accounts, burn their kit and bury their trophies.

“That was hard because it was our achievements,” says Fati. “Who wants to burn their jerseys? I thought, if I survive, I will make [the achievements] again.”

At the same time, Carter was working on the plan to get them on a military plane out of the country at the earliest opportunity. She knew the security situation in the Afghan capital would only become more dangerous. She strongly believed the US and British governments were badly mishandling the situation. And the Taliban were setting up checkpoints.

“Khalida texted all of us saying ‘girls, be ready to leave for the airport together, just one backpack each’,” says Fati.

“She said: ‘We can’t tell you that we are even sure that you will go inside the airport. But if you fight, you will survive.'”

When the time came, Fati wrote Carter’s phone number on her arm in case her mobile was stolen or confiscated. Carter had also told Fati that the players should rotate having their phones switched on to preserve battery life among the group.

Fati left home carrying as little as possible, as instructed. She was wearing long robes that also covered her face. The journey to the airport was fraught with hazards, any of which might stop the players in their tracks.

Popal’s advice had been to pack for three days, just in case. But in addition to a phone charger, clothes and water, Fati couldn’t resist taking another item, even though doing so was a big risk.

“I had one of the national team shorts,” she says. “I wore it like underwear and I was scared about that.”

The situation at the airport was truly desperate. Thousands of people had congregated, some having travelled from the most distant regions of the country.

“People were squeezing each other and trying to go inside as fast as they could,” Fati says.

“It was a matter of life and death. Everyone was trying to survive.”

For the vast majority, the scramble was in vain.

“If your name was not on a list, or there wasn’t somebody inside the airport coming out to get you, you weren’t getting in,” says Carter.

“So we had to work extra hard to make sure that marine counterparts at the gates had their information to make sure that they could get in.”

Carter told Fati that “there will be a guy at the north gate”.

She added: “You should be there at the exact time and write a password that I’m telling you. He will understand and there will be no questions and you guys will be inside.”

That password was the name of World War Two marine hero John Basilone, and the date the marine corps was founded – 10 November 1775 – combined with various other symbols.

“It was communicated to me that that’s what the marines on the gate would be looking for,” Carter says. “Marines are going to know that another marine told her to write that sign.”

But at the north gate, Fati and her group were turned back. The message hadn’t got through.

“I tried to show that code but the soldier was rejecting and saying, what national team? Who are you?” Fati says.

“He said, if you have a US passport we will let you in but no other options.”

In Houston, Carter had to recalibrate the plan.

“My heart didn’t sink at that point because I was in operational mode,” she says.

“I said OK, that’s not a problem, just give me some time so I can recommunicate to the folks on the gate so they know you’re coming.

“I think she was stressed, and rightly so. I was not stressed, because if I’m stressed, that stress is going to convey to her.”

Fati and the rest of the players could only wait.

“If I guess, it was 48 hours we were outside the airport,” she says.

“The weather was too hot, there was no air. The children around us were crying and screaming, and saying, ‘let’s go home, we don’t want to die’. Whenever they heard the gunfire, they were screaming.

“There were so many eyes looking at me to do something, to find a way.”

Fati decided she and the players would try again, this time at the south gate. There were two Taliban checkpoints in the way.

At the first, she was separated from her brother and he was badly beaten. At the second, she was herself kicked and hit by the men with rifles pushing crowds back.

With the weight of responsibility on her shoulders, amid the crush of bodies, the heat and the gunfire, she felt it was over. She felt like giving up.

Then she remembered the text message Popal had sent her: “If you fight, you will survive.”

Fati says: “It was a thing that lighted up that darkness. Suddenly, there was something telling me to get back up and I started again in a strong way. That was a lesson I will keep in my whole life; there’s always a hope, there’s always an open door.”

The players regrouped. Suddenly, taking advantage of a distraction that absorbed the attention of the Taliban guards, they made a dash for the Australian soldiers just beyond, still at the airport’s southern entrance.

“There were so many people but we managed to get past the last checkpoint,” Fati says. “We saw the Australian soldiers and shouted phrases like, ‘national team players’, ‘Australia’ and ‘football’.

“They looked at our documents and let us through.”

When Fati, her team-mates and some Afghan Paralympians boarded a C-130 military transport plane bound for Australia, she sent a photo and message to Carter. “I made it. We made it.”

The C-130 is a no-nonsense transporter of hardware and troops for war zones, and the girls were hosted in the cargo area, trying to get comfortable enough to sleep on each other’s shoulders.

So there were no dramatic final glances down through the window at the place that had always been home.

“The plane just took off and there was just noise and the fear that we had. Looking around, there were just scared faces,” Fati says.

“I was thinking, you will never ever be able to see this beautiful place where you made memories and grew up. It’s your last time.”

In 2010, in their first official match, captained by Popal, Afghanistan’s women lost 13-0 to Nepal.

Regardless of the scoreline, a momentum was established that could only flourish in the relative freedoms of an Afghanistan without Taliban rule.

“We were a voice for all of those who were voiceless,” says Fati.

“It made my parents change their mindset, especially my dad. He had the same mindset of other men who thought that sport is not good for women.

“Some people were thinking we were just trying to have fun. But they didn’t understand that it wasn’t just fun. It was about society, it was about rights.

“Our national team was about all those women who were hidden.”

The team never came close to qualifying for a major tournament like the World Cup or Asian Cup, but under American coach Kelly Lindsey and assistant Carter they did reach the brink of the world’s top 100, despite it being too dangerous for either of their coaches to set foot on Afghan soil.

The most recent official action involving female Afghan footballers came in June 2021 in an under-20 tournament for central Asian nations in Tajikistan.

Two months later came the Taliban’s return.

In Australia, Fati and her team-mates trained together for the first time in February after Melbourne Victory provided facilities and coaches.

“The feeling was amazing,” says Fati.

“I thought, we have our everything back, and there was a new hope for all my team-mates.

“I’ve locked those smiles in my memory. And I thought, I’m successful. We will not be lost.”

In April, they passed another milestone. Coached by former Wales international Jeff Hopkins, who is now the Melbourne Victory women’s coach, they played their first match since fleeing Kabul, a 0-0 draw against a local non-league team.

The Afghan kit bore no names, only numbers on the back of the jerseys – a reminder that while they are safe, their relatives are still at risk of identification and reprisals.

The future looks uncertain. In order to compete internationally in official competition they will need the backing of the Afghan Football Association (AFA), and the approval of the Taliban, which nobody expects to be given.

In September the team was withdrawn from qualifiers for February’s women’s Asian Cup, which China won.

Fifa describes the situation in Afghanistan as “unstable and very worrying”. It says it “remains in contact” with the AFA and “remains committed to growing the game”. But it could not say with any clarity whether Fati and her team-mates would once again be able to represent their country.

Meanwhile, the men’s team have been playing, recently missing out on qualification for the 2023 Asian Cup. The AFA president, Mohammad Kargar, has not responded to an interview request.

Fati remains resolute.

“We are worried about the title of the Afghanistan national team, if we’re going to have it officially or not,” she says.

“If the AFA say no national team, it doesn’t matter because I have my team-mates. We have each other. We will play together or individually. We are already a family and no-one can change it.

“The goals instead will be for us to make the national teams of Australia or the country that we are in. Still we are Afghans and, somehow, we will be the representatives of our nationality.”

Carter finally met Fati in Australia in April.

“She’s an incredible young woman,” the American says.

“It’s not just the resourcefulness but the courage that entire group of young women displayed, Fati being the leader. The resilience and courage that they’ve shown over the last year is breathtaking.

“Those women are my heroes.”