It’s early spring in Romania and driving west from Bucharest on the A1 motorway open country spreads out as far as you can see, earth returning to life in the sunshine.

About two and a half hours from the capital you reach Scornicesti. This is the birthplace of Nicolae Ceausescu, the communist dictator who ruled the country from 1967-1989.

Originally just a village, Scornicesti was razed to the ground and built again as an important agricultural-industrial hub, selected for the honour thanks to its connections with the Ceausescu family. For a long time, the 100km we’ve driven on the A1 was the only stretch of highway Romania had. For the country’s tyrannical ruler, it wasn’t just an ordinary road, it was his way home.

Under Ceausescu, Scornicesti offered better living conditions than many big cities. While millions were starving and had to queue to buy essentials, the shops here never went out of supplies. Life was good, but the people also needed entertainment.

This is where football comes in. In the 1970s, the communist authorities decided to make a statement and co-ordinated the local team’s rise from the amateur leagues to the top flight. In 1987, the most modern stadium in Romania was built for the team: FC Olt Scornicesti.

The aim was to conquer the continent – in emulation of Steaua Bucharest, European Cup winners in 1986.

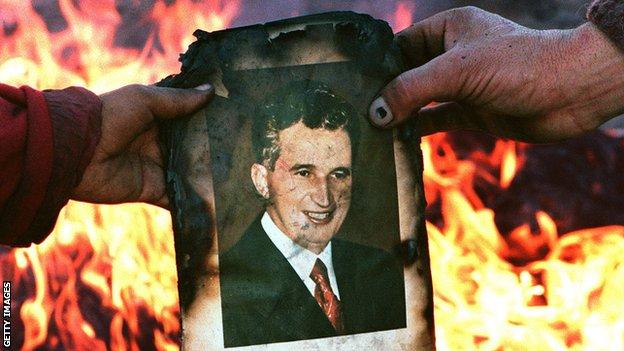

But in December 1989, a bloody revolution resulted in more than 1,100 deaths as waves of protests toppled the Ceausescu regime. On Christmas Day, the ruler and his wife were executed.

Scornicesti, and its football team, would never be the same again.

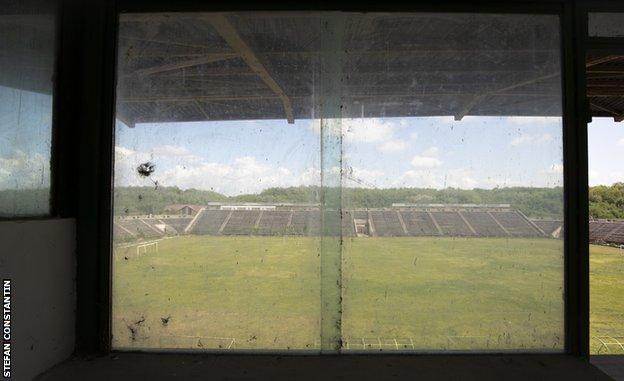

As you enter Scornicesti, the ‘Viitorul’ (Future) Stadium immediately catches your attention.

When it was built, it was the most advanced in the country. It had the first seated-stand in Romania, a mini-hotel, VIP boxes, a lounge, a swimming pool, modern dressing rooms.

The seats are still there, not one missing despite the 35 years gone by. But many of its other facilities have long been forgotten. The hotel rooms are now used for housing by social services, while many of the spaces behind the stands host clothing manufacturers working for English or French brands.

FC Olt, the football team, still play here, an amateur club in the fourth tier. At full capacity, the arena used to hold up to 25,000 people. Now at most around 200 show up for the minor local derbies.

Ceaușescu wasn’t much of a football fan, but some of his relatives were mad about the game. It was Vasile Barbulescu, Ceausescu’s brother-in-law, who insisted a team should be created. He saw it as a way to boost local prestige.

FC Olt’s first fixture in the fourth division was played in 1973. The team turned out on a pitch where locals used to feed their animals. In between matches the goalposts were used to tether cows and horses. But things were about to change.

In 1978, Barbulescu hired a 32-year-old Dumitru Dragomir as chairman. Dragomir had previously worked in two other clubs with good results and was admired for being ‘resourceful’.

He arrived just before the end of the season, when Scornicesti were fighting to get promoted to the second tier. To get ahead of their rivals, FC Olt needed to win their last match of the season by a big goal difference. Dragomir laughs as he recalls how they managed it.

Scornicesti were due to play Aluminiu Slatina, a team that had abandoned the competition and so were forfeiting each game 3-0.

“We needed a result. So we had to act fast,” Dragomir says now. “I told them to get me some boys from the village and dress them in match shirts. Then we needed to convince the team in Slatina to hand over their original playing IDs.

“We got boys from the stables, boys who used to milk cows, and they played as if they were Slatina.”

On matchday, FC Olt’s promotion rivals were playing at the same time. Police support was arranged, with officers placed in a communication relay about 30km from one another so they could talk over radio. They had to make sure the score got to Scornicesti as soon as goals were scored.

At half-time, one of the officers heard a wrong message. Instead of 2-0, he understood that FC Olt’s rivals were winning 9-0.

Those at Scornicesti began to panic and netted 18 goals against their sham opponents, trying to make sure it was enough. On their way to the locker rooms after the match, the players and officials stopped to wait for the result in the other match.

Confirmation finally came that the other promotion contenders only won their game 2-1. Things would have been settled with an extra few minutes added on if required.

The next season, Dragomir, who went on to be Romanian Professional Football League president between 1996-2014, was told he must win promotion to the first tier. They threatened him with exclusion from football if he failed. He succeeded – but only by two points.

According to all those interviewed for this article, Ceausescu himself didn’t care too much about the team. He just asked his brother-in-law Barbulescu to “take care with what he was doing” in Scornicești.

Instead he was a Steaua supporter and regarded the Bucharest military team as a potential European Cup contender. Steaua would indeed be crowned European champions in 1986, also reaching the semi-finals in 1988 and the final again in 1989.

Dragomir only met the dictator once, during one of his visits to Scornicesti.

He recalls: “Ceausescu visited a local factory, then went to our chairman’s home. I was asked to go as well.

“Earlier, my three-year-old son had refused to give Ceausescu’s wife some flowers because he wanted to give them to Ceausescu instead. When I was called and told I had to go and see him I was scared; I thought his wife was unhappy!”

Ceausescu suddenly asked Dragomir to tell a joke. About Ceausescu himself. Faces darkened around the room.

“He insisted,” Dragomir says, smiling. “So I told one about him, Leonid Brezhnev and Richard Nixon being stuck on a ship.

“During the course of eating they were debating who was more courageous: the Russians, the Americans, or the Romanians.

“To make his case, Brezhnev ordered one of his guys, Aliosha, to jump overboard and bring back two sharks, armed with just a sword. Aliosha jumped in the water and brought the two sharks even if it cost him an arm.

“Nixon asked his guy, John, to get three sharks using just a knife. John lost an arm and a leg but got his three sharks. Now it was Ceausescu’s turn.

“He woke up his guy, Bula, who was sleeping: ‘Come on, Bula, I have these two shaving blades, bring me five sharks please.’

“Bula put a finger in the water and paused. Then he said: ‘No can do boss, the water’s too cold.’

“At that the entire ship’s crew started cheering and applauding the courage of Bula’s refusal, so it was decided Romanians were bravest after all.”

All eyes in the room were on Ceausescu. Everyone was waiting for his reaction.

“Elena, his wife, broke the silence,” Dragomir says.

“‘You should be ashamed of yourself!’ she shouted. But Ceausescu said: ‘Well done, young man! Nobody touches this guy, OK?’

“After that, everybody started clapping and they went back to having fun.”

Following promotion in 1979, FC Olt stayed in the Romanian top flight for 10 years. Their best finish was fourth in 1981-82, when they just missed out on qualification for the Uefa Cup.

Former Chelsea full-back Dan Petrescu (1986-87), ex-West Ham and Tottenham forward Ilie Dumitrescu (1987-88), and Romania’s most-capped player Dorinel Munteanu (1988-89) were among their players. Despite modest success, it was an appealing team to join.

In the 1980s, Romania experienced big shortages of products and essential services, even in the big cities. Electricity, hot water, and heating were all rationed. Life was hard even if you had money, and there wasn’t much to spend it on in the very few shops.

But in Scornicesti the picture was different.

“You could find anything you wanted,” says Ion Anghel, a former FC Olt goalkeeper.

“There was meat, milk, eggs, coffee, chocolate, Pepsi… anything I tell you. People would even come from Bucharest to shop.”

Dragomir adds: “Many of the journalists who came to report from Scornicești became my friends. One of them had a new car, I told him to get anything he needed for his family. Meat, eggs, anything, as a gift.

“He left for Bucharest after the game, and I did too but half an hour later. On my way, I saw a big traffic jam. People were out of their houses, fighting to collect these frozen chickens. There were loads of them on the ground.

“I couldn’t understand what had happened until I saw a car in a ditch on the side of the road. It was this journalist with his new car. All the meat landed in the street.

“He was OK, fortunately. The police officers who came to the scene wanted to know where all the meat came from. I just told them: ‘Scornicesti.’ No further questions. They just went to the car to check if there was something left for them to take home too.”

After that fourth-place finish in 1982, FC Olt began to aim higher. In 1985, they started work on a bigger stadium.

Locals say the venue was supposed to stand for 400 years. But did it make Ceausescu proud? According to those who built it, the dictator didn’t even know it was happening.

“He only found out when construction was almost done,” says Mihai, one of the locals who worked on the ground.

“I think his family was scared of how he’d react. One day we were asked to cover everything with cartons so he wouldn’t see it when passing over by helicopter. He was flying over the site with a Bulgarian politician and we were supposed to hide it.”

FC Olt hadn’t even played one top-flight season at their new jewel stadium before the bloody revolution of December 1989 and the dramatic changes that followed.

The team was relegated midway through that campaign. The official reason given was that authorities couldn’t guarantee the safety of players and staff. Ceausescu’s execution meant a bullet for FC Olt, too, because of its ties with his family.

Marius Stan was among those who played at the new arena before the team was broken up. He is now the club’s technical director, in the Romanian fourth tier. When he looks around, he doesn’t see much of the excitement he once knew.

“We had a good team here, a very good team,” he says. “The big games we won, in my time here, were only thanks to our quality on the pitch.

“We didn’t have anything to do with politics. I mean we, the players. We tried to play football for ourselves and our families.”

Stan was on the pitch for FC Olt’s final top-flight match. It was against Steaua. A certain Gheorghe Hagi scored the winning goal for the military club and the game finished with a huge brawl between the teams. Tensions were so high that the referee decided to end the game before 90 minutes were up.

Nowadays, players no longer come from all over the country to join Scornicesti. Stan and chairman Robert Gogot’s job is to keep the team going on very little money. And to convince those around them that their dream of a return to glory is still alive.

The reality is different. Scornicesti is something of a ghost team. It is a reflection of its town; guarded by a necklace of grey tower blocks, the neglected old stadium, and the house where Ceausescu was born.

Its young leave in search of a better life. The 60-year-old Dacia 1300 car, a symbol of the Romanian communist regime, continues to run its streets. The world that gave it life is extinct, but time has not moved on.

“I live in Scornicesti and I’m proud of the heights this team reached,” Gogoț says.

“I’m doing this out of passion. I grew up here, my dad was a team doctor. I know how I felt around the team and nothing can take my feelings away.

“We now have new hopes. We are trying to modernise the stadium. We will sign better players and next season we’ll fight for promotion.

“There’s nothing I should be ashamed of. I’m just happy I got to see the big games, the big players.”