Frank Mill must feel like Marty McFly, the main character from Back to the Future. Regardless of what he’s up to, he is continuously being dragged back to the mid-1980s. To one day in particular: 9 August 1986.

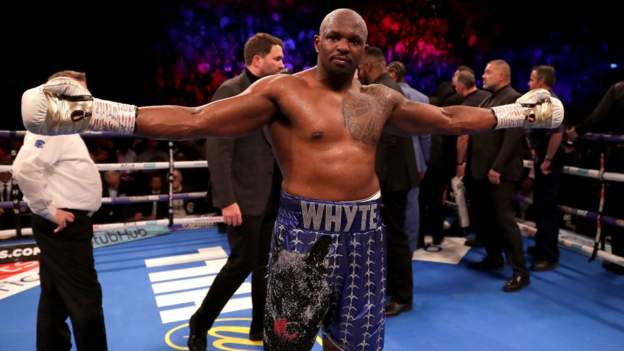

It was Mill’s first game for Borussia Dortmund. Just before half-time, he was played clean through. One pass split the Bayern Munich defence and, after dribbling past the keeper, he found himself in front of an empty goal. What happened next is often described in Germany as the ‘miss of the century’.

Mill waited too long. With an open net in front of him, he took an extra touch to steady himself, slightly to the side of the six-yard box, delaying what seemed like the inevitable. As the keeper came rushing back, sliding in to make a hopeless attempt to block, Mill suddenly ran out of rhythm and the ball held up in his feet. When he finally did shoot, he hit the post. The ball bounced back to a waiting Bayern defender.

Even 35 years on, whenever anybody in German football misses a good chance, it doesn’t take long for commentators to bring this story up. Reporters will call him asking for an opinion. The very act of failing to score from an open goal is known as ‘a Mill’. He’s fielded a lot of questions about Timo Werner over the past few years.

Mill, now 63, is continually forced to recall the actions of his most embarrassing professional moment. He takes this philosophically. He won’t refuse to answer if he has been asked in a proper way.

“Several years ago, I went to a local butcher’s shop with my good old friend Matthias Herget, the former West Germany defender,” he says.

“An old lady behind the counter wrapped our bread and sausages and when she raised her eyes, she exclaimed loudly: ‘Ah! You hit the post!’

“Whenever a guy on the street screams my name and tries to taunt me, I just refuse to react. In general, though, after all this time, I really can laugh about myself.

“It was nuts. I wanted to make the Bayern players look ridiculous, to roll it over the line. But I ran faster than the ball and lost control. It just lay between my legs and then suddenly it happened…”

When the scene was shown on German TV, Mill’s miss went viral, 1980s style. It wasn’t instantly plastered all over the internet of course, but it dominated the tabloid media, while fans talked about it endlessly.

And even back then, it spread around the world.

Third party content may contain adverts

A few months after his miss, Mill went to visit a friend in San Francisco. In his room at the Fairmont Hotel, he’d ordered a burger and switched on the TV. He found a program that presented odd clips from the sports world.

“First I saw a basketball player who tore off the basket while attempting to dunk,” he says. “I laughed and took a bite from my burger. And just at that moment, I saw myself on the screen hitting the post in Munich.”

Normally, such a failure could turn a professional football player – especially a striker – into a reclusive character who might start to overthink his attempts on goal. Not Mill.

Throughout his career, he was known for his personality. His father Bobby worked as junk dealer and Mill truly inherited his fearless tongue and conviviality. He played with no shin pads and often stole the ball from goalkeepers when they were about to kick the ball.

In German, there is saying that could describe such a character, ‘mit allen Wassern gewaschen’, which literally translates to: “washed with all waters”. A better translation would be ‘to know every trick in the book’. But Mill’s Dortmund team-mate Norbert Dickel perhaps summed up his slyness best of all when describing him with the pun: “He is washed with all wastewaters.”

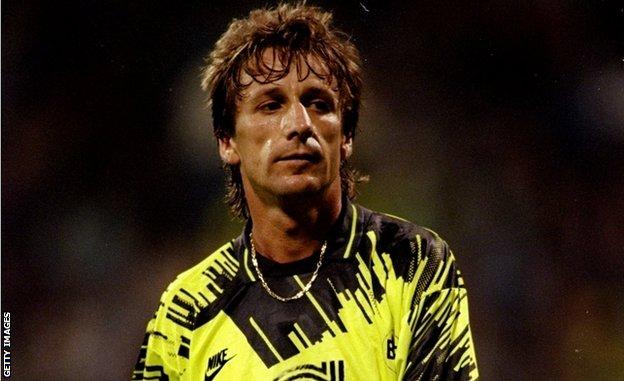

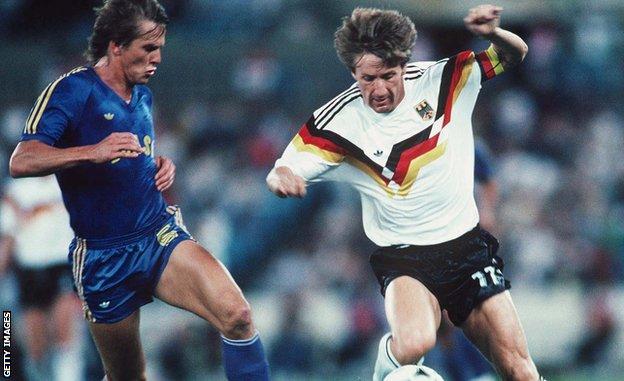

Mill was always self-confident, outgoing and indeed clinical as a striker. He spent 15 years in the Bundesliga, playing for Borussia Monchengladbach, Dortmund and Fortuna Dusseldorf in the German top flight between 1981 and 1996. He represented West Germany at the 1988 Olympics and also made the 1990 World Cup squad but did not feature as Franz Beckenbauer’s side lifted the trophy in Italy, and so does not consider himself a world champion. He scored 253 goals in 656 career matches. Despite being only 5ft 9in tall, his ability to get off the ground so well meant he scored many headers.

But his greatest achievement, in his own eyes, was winning the German Cup with Dortmund in 1989 – three years after that miss against Bayern – when Mill contributed one goal and two assists in an astonishing 4-1 win over Werder Bremen.

When he thinks back to the preparations for that match, he remembers an unusual distraction.

“For many years with Dortmund we trained at a lido on Fridays, and we did exactly the same on the day before the cup final,” he says. “It was a completely different time.

“In the summer, the lawn was used by nudists. We carried our goals to a less busy area and played there, it had a good surface. So at the back of the lido, there lay the naked sunbathers, and up front we practised for the cup final. I really can’t say that all the shots went on target.”

Mill recalls those different times fondly. He remembers how he and his Dortmund team-mates would lock themselves in the tiny kit room and talk for hours over cake, coffee and cigarettes. Or how, with the German national team, somebody placed a live rabbit in the team doctor’s case just before a friendly match. It was agreed Andreas Brehme would fake an early injury, and when the physio ran on to the pitch and opened his bag to treat him, out it sprang.

He is also very talkative when it comes to a topic many former international players want to deny: allegations of doping.

It was former West Germany goalkeeper Toni Schumacher who raised the subject when he released his book Anpfiff (Kick-Off) in 1987. It made claims about not only doping practices but other scandals around the national team, involving poker nights, prostitutes and alcohol abuse. For a long time, no other player shared Schumacher’s views that the misuse of Captagon – a banned branded amphetamine now produced in huge quantities in Syria – was common in the Bundesliga of the 80s.

Mill says: “Strips of tablets lay by the dressing room’s basin and you were free to help yourself. It was ‘trendy’ at that time. The doctors knew it, the managers, everyone. But no-one talked about it.

“Many players took it until they couldn’t walk any more. You don’t see the consequences immediately, but it takes its toll on your body in the long run.”

Mill admits he took Captagon once, without saying before which particular match.

He says: “I scored twice in the game, and afterwards just couldn’t get tired, whatever I tried.

“In the middle of the night, at home, I lit a candle that was placed on a wooden shelf. I wanted to watch the repeat of Aktuelles Sportstudio [a Match of the Day-style highlights programme]. I finally fell asleep, but woke up just in time to stop the fire spreading [as the candle had set the shelf on fire]. I thought to myself: ‘Boy, you very nearly sent yourself up in flames.’ So I shrank back from taking Captagon a second time.”

For Mill, that was the second of the two decisive nights when he watched himself on the TV. Once in San Francisco; the other at home, which was almost his last.

The German media will keep ringing him every time somebody misses a great chance, but he has so much more to tell, about a generation of football that seems several worlds away.