Getty Images

Getty Images“The drama of a player shouting and making a challenge, and the crowd watching the screen and waiting for Hawk-Eye to make a decision, all of that drama is now lost.”

David Bayliss is describing a scene he saw play out many times as a Wimbledon line judge – and one which the Championships won’t witness again.

Just as with the many other sports that have embraced technology, the All England Club is waving goodbye to human line judges from next summer, after 147 years, in the name of “maximum accuracy”.

But does this risk minimising the drama Mr Bayliss fondly remembers being involved in – and which so many of us love watching?

Reuters

Reuters“It is sad that we won’t be going back as line judges,” he says. “The game has moved on, but never say never.”

He served as a line judge and umpire at Wimbledon for 22 years, calling the lines when Roger Federer won his first Grand Slam, in 2003. Being hit by the ball at over 100mph is, he jokes, “quite sore”.

While he’s sad to see line judges go, he says it’s hard to argue with the logic.

“Essentially, we have a human being and technology calling the same line. The electronic line call can overrule the human eye. Therefore, why do we need the line judge to make a call at all?”

Of course, even before Wimbledon’s announcement this week, technology played a big part at the tournament through Hawk-Eye, the ball-tracking system, and organisers are following the example set by others.

It was announced last year that the ATP tour would replace the human line judge with an electronic system from 2025. The US Open and the Australian Open have also scrapped them. The French Open will be the only major tournament left with human line judges.

Does the technology work?

David Bayliss

David BaylissAs the BBC’s tennis correspondent Russell Fuller outlined, players will intermittently complain about electronic line calling, but there has been consensus for a while that the technology is now more accurate and consistent than a human.

Mr Bayliss acknowledges there is a “high degree of trust in the electronic line calling”.

He points out: “The only frustration the player can show is at themselves for not winning the point.”

Whether the tech works is one thing – but whether it’s worth it is another.

Dr Anna Fitzpatrick, who played at Wimbledon between 2007 and 2013, says her “first feeling on hearing the news about the Wimbledon line judges was of sadness”.

“A human element of sport is one of the things that draws us in,” the lecturer in sports performance and analysis at Loughborough University tells the BBC.

While she recognises technology can improve the performance of athletes, she hopes we always keep it in check.

Of course, tennis is far from alone in its embrace of tech.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCricket is another sport where it plays a big role and – according to Dr Tom Webb, an expert in the officiating of sport at Coventry University – it has been driven by broadcasters.

He says that as soon as televised coverage showed sporting moments in a way that an umpire couldn’t see, it led to calls for change in the game.

“I think we need to be careful,” he tells the BBC.

In particular, he says, we need to think carefully about what aspect of human decision-making is automated.

He argues that in football, goal-line technology has been accepted because, like electronic line calls in tennis, it is a measurement – it’s either a goal or it’s not.

However, many people are frustrated with the video assistant referee (VAR) system, with decisions taking too long and fans in the stadium not being aware of what is happening.

“The issue with VAR is it’s not necessarily relying on how accurate the technology is. It’s still reliant on individual judgment and subjectivity, and how you interpret the laws of the game,” he adds.

Need to evolve

Statsperform

StatsperformOf course, there is a temptation to think of technology as something new in sport.

Anything but, according to Prof Steve Haake of Sheffield Hallam University, who says sport has always evolved with the tech of the day, with even the Greeks adapting the sprint race in the ancient Olympics.

“Right back from the very start of sports, it was a spectacle, but we also wanted it to be fair.

“That’s what these technologies are about. That’s the trick that we’ve got to get right.”

Technology is still adding to the spectacle of sport – think of the 360-degree swirling photography used to illustrate the dramatic conclusion to the men’s 100m final at this summer’s Olympics.

And while it is true that some traditional jobs, like line judges, may be disappearing, tech is also fuelling the creation of other jobs – particularly when it comes to data.

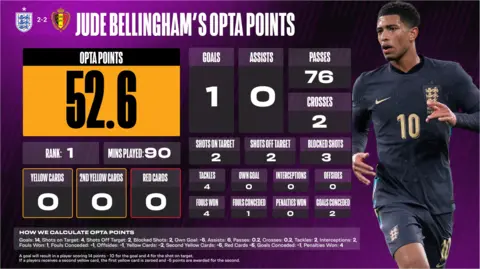

Take the example of sports analysis system Opta, which allows both athletes and fans to have streams of data to measure performance, a process which artificial intelligence (AI) is accelerating.

While it might not be the same as a tennis player’s emotional outburst at a line judge, its advocates argue it allows a more intense connection of its own kind, as people are able to learn ever more about the sports and players they love.

And, of course, the frequent controversies over systems like VAR bring plenty of scope for tech to get the heart pumping.

“People love sport because of the drama,” says Patrick Lucey, chief scientist of Stats Perform, the company behind Opta.

“Technology is kind of making it stronger.”