Dressed in a oversized blazer, Gareth Southgate almost looked like a manager when he was just 18.

Back in 1989, the England head coach was representing Crystal Palace’s youth team on a trip to Portugal alongside Chris Powell, now his assistant coach.

“Our manager Alan Smith was big on that, and who we represented, so we couldn’t take them off despite the searing heat,” says Powell.

“It was a tough, south London environment in those days. Gareth was from the Sussex borders, but he learned to fit in through the force of his personality and how he adapted.

“He was the only one who wore shoes, but when he caught me dancing in them, the room went silent and he knew he had to fit in or otherwise be the butt of the jokes.

“I think we were forged by those moments in the Palace youth team. He ended up being captain and I left the club, so we went a different route, but it has brought us back together.”

Powell’s memories show a hint of the character of the 50-year-old who has led England to a first major men’s tournament final since they won the 1966 World Cup.

While Southgate is liked and respected throughout football, he also has an inner strength and conviction which has translated into the type of leadership that has inspired the nation.

These are some of the stories which helped make a man who has already created history – and now stands on the verge of becoming an English football legend.

‘I’m at Palace next year’

Southgate, a boyhood Manchester United fan, attended Pound Hill Junior School and Hazelwick School, both in Crawley, Sussex. He has said both schools were “fundamental” in him taking up football, largely because of his PE teachers. Dave Palmer taught Southgate at Hazelwick.

He was very self-assured. I remember the last chat I had with him as a schoolboy. We were talking about the future and I was asking the boys what they would be doing the following year.

Gareth said ‘I’m at Crystal Palace’ and it dawned on me that was what he would be doing. As a 16-year-old, he was talking with absolute certainty.

In those days, 60-odd boys used to turn up for football trials when they joined the school. He stood out straight away because he was so classy and had so much time. He used to glide around the pitch.

He was a multi-talented sportsman. He played rugby for the school, to the extent that when we went on a football and rugby tour to France, Gareth played both sports. He was quite quick, 200m was his best track event, but he also won the county championship and held the school record in the triple jump.

He was mature, had a good sense of humour and a big smile. He was respected by his peers and teachers. He was very thoughtful and clever, as well as having a sharp wit. He set himself him high expectations in everything he did, whether in the classroom or on the sports field.

There’s always a discussion when someone has so many different talents about where they go in their life. He could have taken an academic route or a sporting route. So many boys I’ve known have had high hopes in football, but there’s never any certainty. Gareth was sure he was on the right path.

‘I told him to become a travel agent’

Southgate was released by Southampton as a youngster. He came to the attention of Palace youth team manager Alan Smith, who later made him captain of the first team. Even after they both left Palace, Southgate and Smith remained close. He visited Smith within 24 hours of missing the Euro ’96 penalty that saw England lose to Germany in a semi-final shootout. Later, when manager of Middlesbrough, he took Smith to Teesside as an adviser.

I had a doubt whether or not he had a career in professional football in him. We had one particular game, which we lost, and I called him into the office and said: “Gareth, I think you’re too bright to do this job. I think you have to make a choice. If it was my choice, I think you should become a travel agent.”

He was upset, but he took it on board. Instead of releasing him, I decided to go the other way and made him captain of the youth team because I thought he had leadership qualities. Not because of what he said, but the way he went about his job.

I introduced him to an estate agent friend of mine that got him to do some work after training. He was measuring up, mundane stuff, looking to see if a property could be marketed or not. All of these things help build the character you become. It opened his eyes to what was out there and showed him what it was like to deal with people outside football.

I was there when he threw up over the chairman Ron Noades. It was a trip abroad and I had let the lads out for one night. Ron had his white shoes on and Gareth managed to do it. I heard plenty about it from Ron the next day. I can’t repeat what Ron’s words were, but I do know Gareth was very apologetic.

No-one can say he has had it easy. He has had to fight for everything he has got, even if he did come from a middle-class Crawley background. To miss the penalty at Euro 1996, to be sacked by Middlesbrough, these are things that chip away at you. They have made him a stronger character.

I know he went for one manager’s job many years ago and he didn’t get it because he was told he was too polite. He has principles. That does put him slightly aside from others. He has real loyalty, he hasn’t forgotten his roots. These are all things that make up his DNA, that led him to the England job.

‘He was better at song titles than penalties’

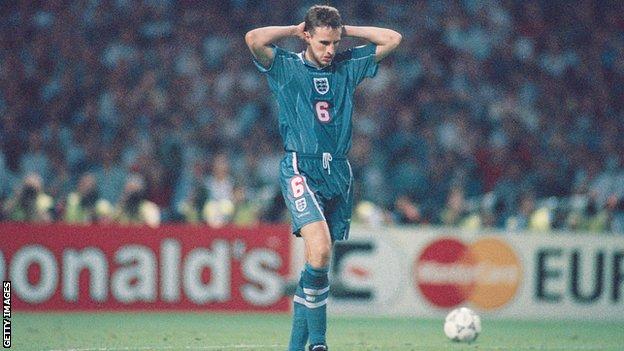

Southgate played every minute of England’s Euro ’96 campaign, which ended with his decisive penalty miss. When he became England manager, he said he did not think he would ever have to go through a worse experience. Alan Shearer was part of the England team that night at Wembley.

Not long ago, I made a documentary about Euro ’96 and I asked Gareth if I could speak to him. He politely declined because he knew the one thing we wanted to talk about was the penalty miss and he’d had enough of it. Still, to this day it will be hurting him.

He took a penalty because he’s brave. The manager was looking around for characters and one or two put their heads down, not wanting to take a penalty. That wasn’t Gareth. After the five designated penalty takers were allotted, the manager was asking ‘who’s after that?’ and Gareth stuck his hand up.

I would never criticise anyone that has the courage, the balls, to put his hand up to take a penalty, particularly in those circumstances. When you have 90,000 in the stadium, 10 or 15 million watching on TV, it takes a certain character to put his hand up to take a penalty. There was nothing that I, nor anyone else, could say to make him feel any better.

Two years later we were at France ’98. Tournaments can be a bit boring, doing the same thing for four or five weeks. We came up with the idea to fit as many song titles as possible into the interviews that we gave.

Because the players’ room was next door to the TV room and the interviews were going out live, once we got the song title in, you could hear a roar when the players realised you’d done it.

Gareth managed to sneak Club Tropicana and Careless Whisper into an interview with Bob Wilson. He was definitely one of the brighter ones, so he was better at that than most. He was certainly better at song titles than he was at taking penalties.

‘He was already like a manager’

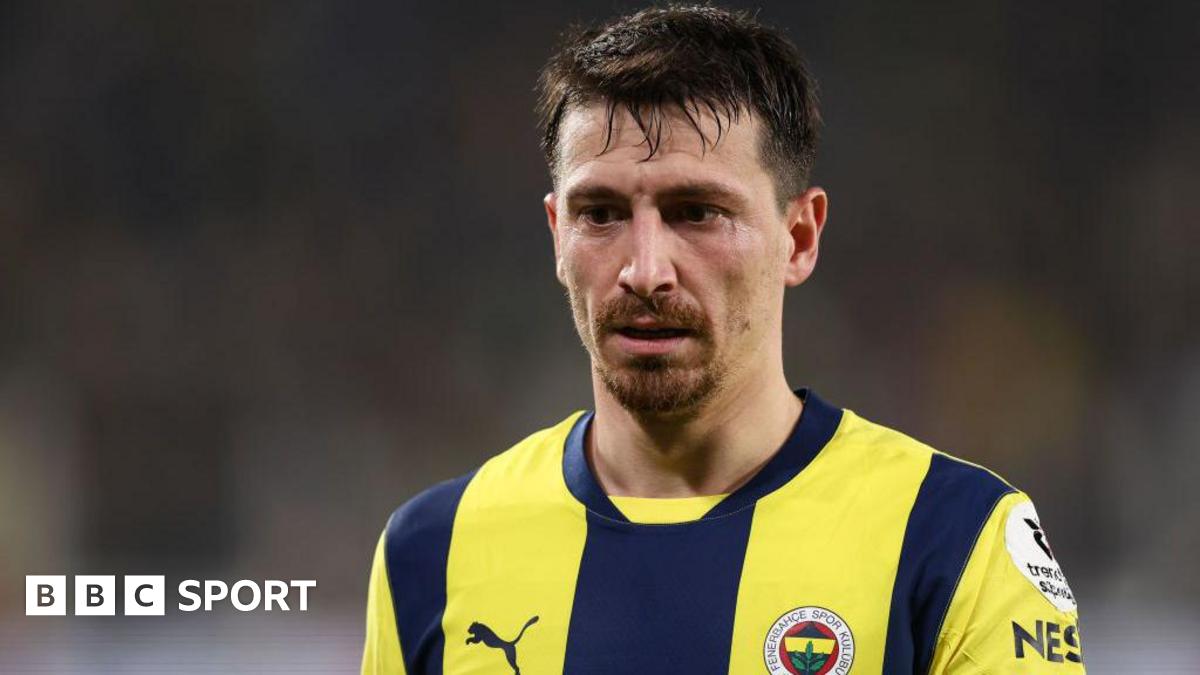

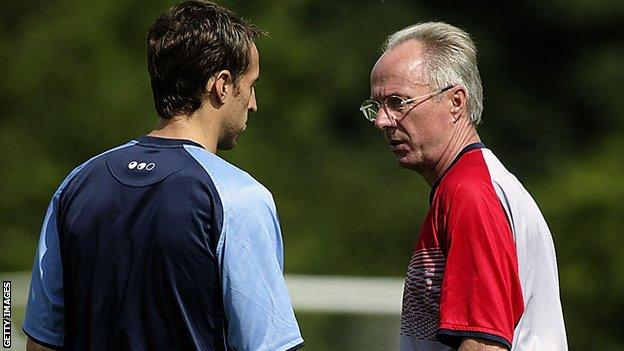

Southgate had caught the eye of Sven-Goran Eriksson when the Swede was manager of Lazio. When Eriksson became England manager in 2001, he had to manage Southgate’s disappointment at falling behind Rio Ferdinand and Sol Campbell. Southgate was part of the England squad for the 2002 World Cup, but did not play a single minute. He won the last of his 57 caps against Sweden in 2004, two years before the end of Eriksson’s spell in charge.

He came to me and asked for a meeting. He wanted to know how to make himself better. That’s not easy, to keep working, on and on to make yourself better than players like Sol Campbell and Rio Ferdinand. It’s a little unusual. In my experience, players don’t come to the manager.

He wants to resolve problems with talks, more than with shouting. It was easy to speak to him. He was never angry or irritated, always very polite.

I could see he was a thinking man. He thought about the training we did, why we did something in a certain way. You could see he lived for football. He was very eager to learn and I wouldn’t be surprised if, at that time, he was thinking of being a manager in the future.

I have had many players who are not interested in who the opponent is, they just want to play, but he was never the sort of player that did his training, then left without thinking about it. I’m quite sure he took it home with him. When you have players like that, you can see in the future they will be coaches or managers.

When he was a player, he was already like a manager, a coach. I’m sure that Southgate, in the past, has talked to a lot of managers with a lot of experience, trying to find out secrets and advice. He is a good talker, but an even better listener.

‘They nicknamed him ‘Insurance’ at Boro’

Southgate ended his playing career to become Middlesbrough manager in the summer of 2006. At 35, he was the youngest manager in the Premier League. He guided Boro to 12th and 13th over the following two seasons, but presided over their relegation in 2009. He was sacked on 20 October 2009, despite the club lying fourth in the Championship. Michael Caulfield was the Boro psychologist soon after Southgate was appointed until they were relegated from the top flight.

When he was still playing, his Boro team-mates nicknamed him ‘Insurance’. George Boateng said whatever happened up the field, they knew they had Gareth behind them, ready to be used if needed, like an insurance policy.

He went from being a player in May to the manager in June so the dynamic had to change. He understood he couldn’t be their best mate, but the players knew he was a good character and would treat them right.

In our last home game of the 2008-09 season, we had to beat Aston Villa otherwise it was pretty certain we’d go down. We drew 1-1. When the final whistle was greeted with boos and jeers, a lot of managers would have shaken hands then disappeared down the tunnel.

Gareth marched into the centre circle to applaud the fans. Even though he wasn’t being well received, he made sure he turned to all four corners of the ground. It was fight or take flight and he never looked back.

‘He has a passion for working with the younger players’

Previously the England Under-21 manager, Southgate replaced Sam Allardyce after one game of England’s 2018 World Cup qualifying campaign and led them to the semi-finals in Russia. Assistant manager Steve Holland has been with Southgate throughout his tenure as England boss and with the under-21s.

I started working with Gareth in 2013. I didn’t know him, but when I got to know him, it was pretty apparent he was a decent and completely stable person. That’s always a good start because in football you don’t always find too many in that category. Clearly, he had a passion for working with the younger players. He knew them all and had a drive and vision to show that English football could be better represented.

In every area, he reflected on what is the best-case scenario to create the best possible culture to help the team win. So when you’re talking to players about behaviour, and one of the big players does something that doesn’t fit into that, what are you going to do? His consistency, how he speaks to people and how he behaves, is the biggest driver of the culture.

Scars that certain groups of players had in the past started to define the culture. But if you look back to Russia, a lot of players had less than 10-15 caps so they aren’t tainted and you have a chance to form a different way of thinking. I like the evolution of leadership from that core group from Russia – and the influence and combination with the younger ones. Somebody like Jordan Henderson has got Jadon Sancho in the gym boxing. Why? Because he knows Jadon goes to his room, and now he’s trying to influence and push him physically.

‘He still wants to learn’

Southgate made Chris Powell his assistant coach in 2019 and has spoken of how important it is to have a team which represents modern Britain. Many of England’s players have been racially abused both online and on the pitch, most notably when England faced Bulgaria in a Euro 2020 qualifier in 2019. Southgate has supported the players’ stance in taking a knee despite it being booed by some fans before, and during, the European Championship.

Gareth is a thoughtful person. Culturally, we are all English and our backgrounds are totally different, but we are together and here for one thing: to represent the country. He recognises there have been [racism] issues over the years and still are – and he wants to learn. He says ‘I’ve never experienced some of the things you have’ and asks me about it. He called me before Bulgaria, and we had a meeting with senior players before the start of the Euros.

He wanted to hear it from my point of view and also what young players have been through. I’ve spoken to players too and tried to go the best way for each individual. His support for taking the knee has been great. He knows it may not be the perfect way but people are still talking about it. It may take years [to change] but we’ve started the conversation and I think it’s always going to be there now and I’m proud of that.

With anything, ultimately, it’s Gareth’s decision. But he listens and wants you to be able to sit there and join the conversation. If you see anything he’s missed, he wants to know. He’s the modern-day manager in how you do things and I think he’s setting a benchmark. He’s very engaging with people and gives his time. He seems to work a 25-hour day to ensure people get his time. I don’t know how he does it.

A version of this feature was first published before the 2018 World Cup.