As he perches his near 7ft frame on a bench press at the paint-peeled Filathiltikos basketball club, fate seems to smirk at Giannis Antetokounmpo.

When he was a teenager on this Athens court, he would have to wait for his brother, Thanasis, to sub out and give him the one pair of trainers they shared before he could enter the play. Now the floor is swarming with local kids in box-fresh, top-of-the-range basketball shoes with his name on them.

In the city beyond, he used to work as a wandering street vendor, flogging knock-off bags and sunglasses. He is still out there now, only in the form of billboards bearing his beaming face for various global and domestic brands.

For his first 18 years, Antetokounmpo never left the country, but was never Greek. Now, after six years based in the United States, he returns as perhaps the most famous Greek alive, a multi-millionaire and the best basketball player in the world.

“It is insane,” the 24-year-old says.

“Where we were then and where we are now, is an unbelievable journey. It is beyond my imagination.”

Antetokounmpo was born in Athens in December 1994, the second son of Veronica and Charles, who had left Lagos in Nigeria in search of a better life.

They found the peace they wanted but only in stateless, paperless limbo. Despite being born in Greece, neither Giannis, his older brother Thanasis, nor younger siblings Kostas and Alexis were able to claim Greek citizenship. As illegal immigrants, Charles and Veronica certainly couldn’t.

Greek government policy gave them no right to stay, but the family had no desire to leave. Instead, the six of them spent their nights crammed into a two-bedroom flat in Sepolia, a humdrum neighbourhood in the north of Athens, and their days finding what work they could without papers.

Charles did odd-jobs, while Veronica babysat or accompanied Thanasis and Giannis as they tried to turn passers-by into buyers of cheap eyewear and accessories.

“We sold many different things – watches, handbags, sunglasses, key rings, CDs, DVDs. Whatever we could put our hands on,” Giannis recalls.

“I was amazing at it. My brothers will tell you. Selling stuff and hustling – I was definitely one of the best, because I loved doing it and I loved spending time with my mum.

“That background as a kid is where my work ethic is coming from. I saw my parents every single day working hard to provide for us, it was unbelievable and has stuck to me my whole life.

“I don’t do it because I want to get fame, because I want to get money, that is just how I am built and how I am and all that comes from my parents and how they hustled.”

In what little leisure time he had, Giannis’ dreams were not of hoops, but goals.

His father Charles had been a keen footballer, but as his hopes of making it professionally and changing the families’ fortunes faded, he passed the torch to his sons.

Olympiakos was Giannis’ team. He idolised their Brazilian forward Giovanni and Arsenal striker Thierry Henry. His and Thanasis’ playground commentaries featured them in the Champions League final rather than the NBA play-offs.

That changed on a chance encounter.

Spiros Velliniatis, a basketball talent scout and coach, had identified the untapped potential in Athens’ migrant communities. As he wandered through Sepolia one day he spotted a 12-year-old Giannis and his brothers.

“In Sepolia there are two courts next to each other. On the other, they were playing basketball, but Giannis and his brothers were just chasing each other,” Velliniatis says.

“It’s not only that I saw a person with supreme perception and change of direction, there was also a passion for victory. If you have your eyes open you can see talent in a person without a soccer ball at their feet or a basketball in their hands.”

At this point in life, while his future NBA peers had already amassed thousands of hours of experience and skill, Giannis was starting from near scratch, learning to dribble and make a simple lay-up.

Velliniatis fought on two fronts to unlock Giannis’ latent potential. He had to convince the Antetokounmpo family that pursuing basketball was worthwhile, while persuading a team that Giannis was a project worth risking.

“It was a double-pronged game,” he says.

“With kids from Africa, often the family doesn’t respect basketball. Soccer or athletics are the only options for a career that makes money.

“On the other hand, the big clubs in Greece know the cultural difficulties that can come from bringing in kids from these marginalised communities.

“They think two or three African kids can start making a team within a team. They know that social problems in their neighbourhoods, the need for kids to work, mean they might not be there for practice.

“It is not necessarily a problem of their racism, but of how society is.”

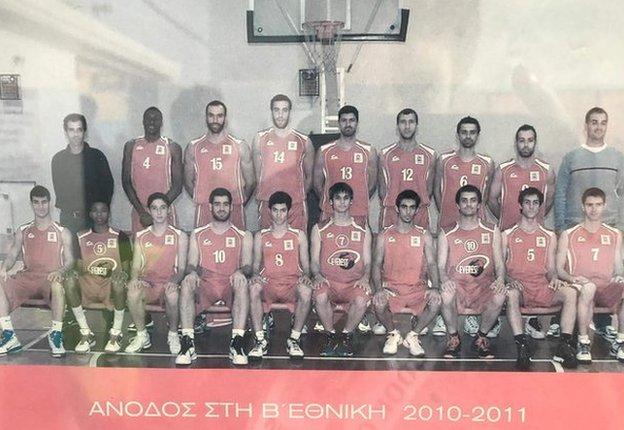

Filathiltikos – in the third tier of Greek basketball and desperate for young talent, regardless of background – offered to find steady work for Charles and Veronica if Giannis and Thanasis committed to regular training sessions.

And the brothers were committed. Some nights they would sleep on foam mats at the gym, too exhausted to get back to the Sepolia flat they were rapidly outgrowing.

Their fraternal rivalry drove them both to improve. They watched YouTube highlights reels of NBA greats in internet cafes. Allen Iverson, the Philadelphia point guard, was a particular favourite for Giannis, inspiring him to braid his hair in cornrows and to practise extravagant crossover dribbles.

At 17, Giannis and his brothers were still helping shore up the precarious family finances by charming and cajoling sales of cheap fashion out of strangers. But there was a moment when Giannis realised an alternative might be materialising.

“I was 15, we were at summer practice and Thanasis was the star of the team then,” he remembers.

“We were practising, he went on a drive and I knocked the ball out of his hand. He was chasing after me, but I held him off and dunked over him.

“When I got home, the first thing I did straight through the door was tell my dad what happened. I realised that if I can do this against my older brother – the guy who knows my strengths and weaknesses best of all – I can do it against anybody.”

The sight of Giannis galloping into the paint and soaring into sky-hooking dunks has become commonplace this year in a season in which he won the NBA’s Most Valuable Player (MVP) award.

It was less so back then. The pterodactyl-like wingspan might already have been there, but he was still skinny, bordering on spindly. In the congested lanes below the basket, he would be shunted, bumped and shackled.

Instead, Filathitikos coach Takis Zivas used him as a play-making point guard, like Iverson, tasked with leading the team out of defence on break-neck fast transitions.

The role developed his pace, dexterity and decision-making just as – eating properly for the first time and starting to lift weights – his frame began to fill out and continued shooting skywards.

What emerged was an intriguing prospect: a towering, hugely athletic all-court player with the ability to shine across all five positions.

In one of his final games with Filathitikos’ youth team, his dominance delivered 50 points. Without a passport, a citizen of nowhere, Giannis was denied higher-profile showcases. He was barred from playing in the top-tier of Greek basketball and representing the nation’s age-grade sides.

But the buzz could not be contained. Videos of his performances lured NBA scouts, more used to trips to Athens in the US state of Georgia, on to 10-hour trans-Atlantic flights.

In all, 29 of the 30 NBA franchises made the big journey to Filathitikos’ small arena to assess Giannis before the 2013 draft. Only the New York Knicks missed out.

The question mark that will have loomed largest in their reports was something he could do nothing to dispel. His lack of a passport meant he could not travel to the United States.

Eventually, on 9 May 2013, after two years of petitioning and less than two months before the draft, the Greek government granted Giannis citizenship and a passport, even if the anglicised spelling of his name that he preferred – Adetokunbo – was mangled to its current form on the document.

The Milwaukee Bucks’ decision to pick Giannis at 15th in the draft seemed a little high to many for an off-radar project player from outside the mould.

Six years later, it seems inspired.

Giannis, having started the game so late, has continued on a steep upward curve of improvement. Tactically, he is smarter. Physically, he is stronger. Mentally, his competitive edge is still razor sharp, unblunted by his new environment and wealth.

This season, he led the Bucks to the play-offs for the first time in 18 years, though they lost to eventual champions Toronto Raptors in the Eastern Conference final.

Individually, he has become one of the league’s superstar totems, revelling in the nickname ‘The Greek Freak’. The stats show his ability. But you don’t need numbers, just eyes. His rare cocktail of range, speed, agility and power leave defensive enforcers cowering and floundering on his way to the rim – while at the opposite end, he is the best defender in the league’s best defence, reeling in rebounds with his tentacle-like arms.

In between, he covers the middle of the court in just a few yawning strides and, when his ominous incoming presence has spooked the opposition out of shape, he has the ability to find a better-placed team-mate.

If he can add a three-point shot to his arsenal – this summer’s off-season project – then his name enters into the argument over the most complete players in the history of the game.

Either way, next year, under the league’s intricate wage cap rules, his excellence has made him eligible for a five-year contract extension worth a record-breaking £195m – equivalent to £750,000 a week.

As he stood in front of the audience making his MVP acceptance speech at the NBA awards a week ago, his thoughts were of his past, not his future.

He tearfully paid tribute to the team that had been alongside him longest and its missing member – thanking his brothers, his “hero” mother and late father Charles, who died suddenly of a heart attack in September 2017.

“I was embracing the moment, but I can’t go back and watch the speech,” he says.

“I still get emotional. When I looked out at the people, I saw my whole life up to now. I thought: ‘How the hell did I get here?'”

His own indomitable will is the main and obvious answer, but his distinctively Greek upbringing played a part – Velliniatis’ vision, Zivas’ tactics, the free pre-training sandwiches provided by Sepolia cafe owner and basketball fan Giannis Tzikas and, most of all, the eternal hustle that was necessary to survive as an immigrant family in Athens.

But if Greece shaped Giannis, Giannis is also remaking Greece.

The Barclays Center in Brooklyn was empty – apart from one section of a couple of hundred people who stayed long after the players had left the scene of the Bucks’ win over the Brooklyn Nets.

As a tracksuited member of the visiting team stalked back out from the locker room, they – ostensibly a home crowd – started cheering.

They fell silent as a young girl, nervously clutching a microphone and her lines, launched into a speech.

“Every time we hear you sing our national anthem, we are flooded with feelings of joy and emotion,” she said.

“Υou are an all-star as a basketball player, but for us you are also an all-star as a human being.”

Giannis touched his hand to his heart and thanked the crowd, also in Greek.

The same scene has played out, with occasional folk song sing-a-longs in other major North American cities, like Toronto, Cleveland and New York.

When the Bucks are on the road, American-Greeks come out to see their national hero. Yet that same vivid national identity is at the heart of why Giannis’ early life was so hard.

For centuries, Greek nationality has been bestowed on the principle of jus sanguinis – the right of blood – rather than jus soli – the right of soil.

Being born and brought up in Greece did not earn Giannis, his brothers and others like them citizenship.

However, a child born elsewhere in the world with at least one Greek parent is automatically entitled to a passport and a stake in a tradition based around descent, history, religion and language.

The global downturn of the late noughties brought Greece’s economy to the brink of collapse and frustration and tension to the surface.

Giannis, who once had hid in a shop doorway to escape a pack of far-right would-be assailants during his youth, became a kind of shorthand in the political discussion.

In 2013, Nikolaos Michaloliakos, leader of the far-right Golden Dawn party that would go on to attract nearly 10% of the vote in the following European elections, called for Giannis to be arrested and deported, and compared him to a “chimpanzee”.

In 2017, a university professor wrote online that he was “a black man pretending to be Greek”, unleashing a furious social media reaction.

Another party ran under a slogan imploring Greeks to be friends “not just with Giannis, but with every Giannis” in the country.

Giannis’ take is simple and short.

“If you are black or white, it doesn’t matter. If you were born in this country and grew up in this country, you are Greek.

“What else can you be? You are what you know.

“A lot of people ask me: ‘Are you Nigerian?’ Yeah, of course I have my Nigerian roots – my parents are Nigerian – but Greek is all I know.

“Why am I less Greek than you? Why? Because I am black? Are you going take my nationality because of my skin colour? Come on, man.”

As Giannis made his way to his childhood court in Sepolia on Saturday night for a promotional event, security struggled to hold back fans, mostly white, as they tried to touch his gigantic frame.

The high-rise balconies above were thronged. The same three letters that have been chanted at the Fiserv Forum in Milwaukee this year bounced off the concrete below: “M.V.P! M.V.P! M.V.P!”

Giannis, who cleaned toilets and picked up cigarette butts during his military service in 2016, has been an exemplary ambassador for his country.

When cameras caught his polite-but-firm refusal to sign a proffered Greek flag in New York out of respect for the symbol, the footage became a viral sensation in his homeland.

But has the veneration of one individual hidden the stagnation for those left behind in marginalised communities?

Giannis believes not.

In July 2015, two years after his passport was controversially issued, the Greek government passed law 4332, which eased the path to citizenship for children of foreign parents born and educated in Greece.

“It is getting a lot better. I have already seen it. People are a lot more open-minded. It is going to happen,” says Giannis.

“They have changed that law – and I think that has a little to do with me.

“A lot of kids from migrant parents are going to get their opportunity like I did. There are lot of kids who are going to be special. Just give them the opportunity.”