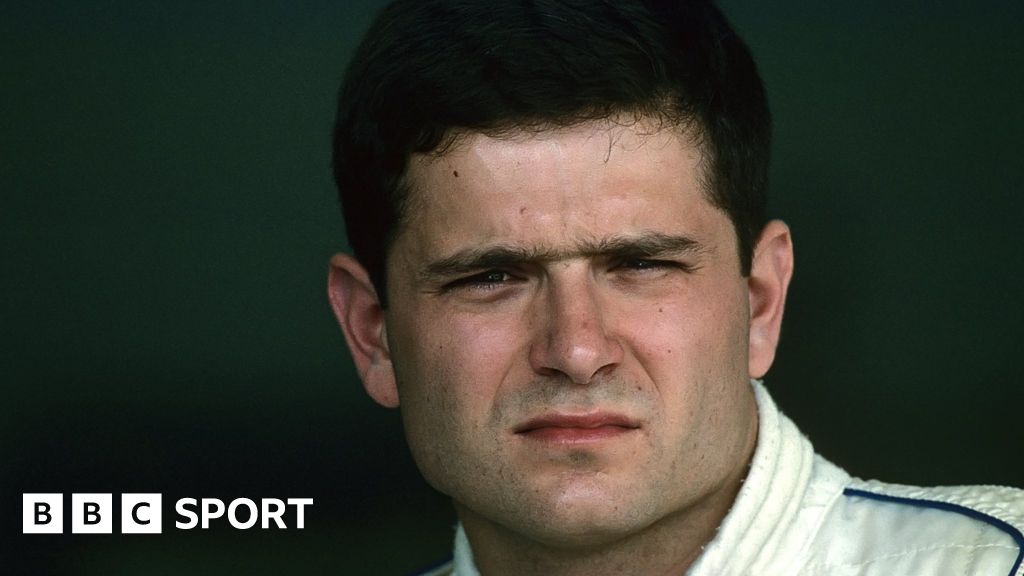

Gil de Ferran was a fantastic racing driver: winner of the Indianapolis 500, two-time Indycar champion and holder of the world closed-course speed record.

But he was respected throughout motorsport just as much for being a wonderful person.

De Ferran – as his great friend and mentor, the US motorsport titan Roger Penske said on hearing of his death from a heart attack at the age of 56 – was “class personified”.

Highly intelligent, eloquent in the extreme, the Brazilian’s insights and expertise were valued across the sport. None more so than by this writer. I have been fortunate to call De Ferran a friend since we first met more than 30 years ago, and time and again I have turned to him for understanding and knowledge.

Of infinitely more importance, so did the sport’s luminaries.

When McLaren needed someone to help guide Fernando Alonso through the intricacies of Indianapolis when the two-time world champion was embarking on his rookie experience there in 2017, it was De Ferran to whom they turned.

De Ferran was there as a sounding board throughout Alonso’s month of May. The Brazilian was wowed by Alonso’s talent; Alonso was just as impressed by De Ferran’s calm, thoughtful guidance. They became firm friends.

From there, De Ferran became McLaren sporting director and was one of the key insiders instrumental in guiding the team back towards the front.

That relationship came to its natural end in 2021. But after McLaren again slipped from competitiveness through 2022, leading to the appointment of Andrea Stella as team principal in December last year, they again turned to De Ferran.

It was at the Miami Grand Prix in May this year that this came to light. I hadn’t actually seen that De Ferran was there initially – he was a discreet presence in his civvies – but I bumped into his daughter Anna, who told me he was back working with the team. She immediately realised she probably shouldn’t have said anything, but we laughed about it, figured he wouldn’t mind too much, and conspired not to tell Gil about her slip-up.

“We call him the Team Doctor,” she said, the joke not hiding the inherent truth of his new role as a consultant employed to help fix McLaren’s problems.

I never told Gil his daughter was the source who enabled me to break the story of his return to F1 to the world. I was waiting for the right time. I knew he’d laugh about it. He laughed about so much. Now I wish I had.

McLaren were one of the stories of last season as they jumped from lower-midfield to the front mid-season. De Ferran’s presence was low key – he preferred it that way. But for Stella, his role was invaluable.

“Gil, most people know him as a champion in Indycar and so on,” Stella said, “but personally I know him for being somebody incredibly competent in motorsport, Formula 1, strategic approach, people coaching.

“When somebody in the team has a conversation with Gil, they always come out quite inspired and like: ‘Ah, I think I understand now better what I have to do.’ Or with ideas: ‘I think I have a concept to work on now.'”

De Ferran was a warm and friendly presence. We first met in the back of the Paul Stewart Racing transporter at the British Grand Prix Formula 3 race in 1992. De Ferran was romping to the title that year, but he’d had a bad afternoon in the rain. Still he was charming and welcoming. We hit it off immediately.

A while later, he invited me and another journalist to dinner at his house in Cobham in Surrey, with his then-girlfriend Angela, soon to become his wife, and David Coulthard, a friend and rival.

I covered his Formula 3000 seasons in 1993 and 1994, in the second of which he came so close to winning the title. When the big F1 opportunity didn’t come, he turned to America, and I was in Miami for his first IndyCar race. He was immediately quick.

Driving for the unheralded Hall and then Walker teams for the next five years, he was a regular contender, but it was in 2000 that his big breakthrough came, when he was signed by the Penske team – the equivalent in Indycars to Mercedes or Red Bull now in F1.