What goes up must come down, right? Not necessarily.

The odds may be stacked against any newly promoted side in a Premier League packed with some of the world’s richest clubs, many of whom have decades-long head starts on any newcomer.

However, that hasn’t stopped a fair few teams overachieving to remain amongst England’s elite beyond that first treacherous season.

There are no hard and fast rules for how to stay up, with every club unique in its approach – but there are some common factors.

BBC Radio 5 Live’s Monday Night Club has spoken to four people with expert insight into the process of remaining in the Premier League after promotion – former Sheffield United boss Chris Wilder, ex-QPR defender Nedum Onuoha, football finance expert Kieran Maguire and Luton Town chief executive Gary Sweet.

The manager – Chris Wilder

Wilder not only took Sheffield United up to the Premier League and kept them there for a second season, he did so with aplomb.

Fourteen wins (including victories over Arsenal, Chelsea and Tottenham) to help amass a points haul of 54 sealed a ninth-place finish – the club’s highest since 1991-92. At no point were the Blades in serious relegation trouble, instead flirting with possible European qualification at stages in the season.

A kind initial fixture list was one aspect Wilder identified as important for his side’s survival, with early games against Bournemouth and Crystal Palace enabling them to get points on the board and build confidence that helped propel them to 13 points from their first 10 matches.

In contrast, Norwich, who won the Championship ahead of Wilder’s side in 2018-19, had a tougher start, including a trip to Liverpool (which they lost 4-1). The Canaries picked up some surprise wins, but these were too few and far between, meaning a return of just seven points from their initial 10 fixtures. They were relegated at the end of the campaign.

“When we were promoted we were talking to a few people and the fixture list was something that came up and was discussed – just how friendly was the fixture list,” recalls Wilder.

“It can be absolutely horrific. I felt for Norwich because we went up as runners-up behind them but their fixture list at the start was incredibly tough.

“And then it’s about how you deal with disappointment. How do you deal with losing 5-0? How do you get over that quickly? Because you have to.”

Wilder is not wrong. It is almost inevitable as a promoted side that you will get a pasting every now and again in a top flight full of some of Europe’s best clubs.

Norwich’s 4-1 loss to Liverpool in 2019-20 cast the die for a season in which they conceded 75 goals.

Two seasons later, in 2021-22, after bouncing straight back up after relegation, City shipped 84 goals, with another opening day loss to Liverpool (this time 3-0) followed by a 5-0 hammering at Manchester City.

They never recovered, taking two points from their opening 10 games and finishing with just 22 in total to drop down again.

Wilder also stressed the importance of adapting your game for superior opponents whilst not losing the core qualities that made you a success the season before. It is something he was able to do well in 2019-20, surprising many with his effective use of overlapping wide centre-backs in a 3-5-2 formation.

He points to Burnley as a fascinating test case for this in 2023-24, with the Clarets having dominated the Championship under Vincent Kompany, playing a possession-based game that will be difficult to replicate against superior Premier League sides.

“I’m sure they’ll be absolutely fine because they’ve got a magical manager in Vincent Kompany,” adds Wilder. “But they’ve had 60-70% of the ball all season. To change and how they’ll deal with that will be interesting to see.”

The player – Nedum Onuoha

Onuoha was part of the QPR squad that stayed up by a point on the final day of the 2011-12 season after having being promoted from the Championship the campaign before.

The defender joined the club in January, after Mark Hughes had replaced Neil Warnock as manager, and played 16 games as their form improved and they amassed the points needed.

He stayed with them after they went down at the end of 2012-13 and helped the club make an immediate return to the Premier League the following campaign.

Onuoha, now 36, says a strong squad ethic and spirit are key to defying the odds in that first season. If that breaks during the season, a club is in trouble.

“Whenever I’ve been in a team that’s doing well you can have people from all different walks of life yet everyone just enjoys the football and enjoys being there,” says Onuoha.

“But when things get tough you start to realise everyone has a different opinion on what you need to do to get better.

“If you’ve not got the right make-up of players in your group you start to see splinters develop in the squad.”

A unity between team and fans – both initially buoyant after promotion – can help maintain team spirit. A key component of this is the ability of a newly promoted side to harness home advantage.

“The teams that stay up tend to have a good feeling when they’re playing at home,” adds Onuoha. “When all their fans are there, they can get some results and that gives them a sense of hope.

“But if you have your fans coming to see you and it’s terrible, before you know it that sense of doom is there, fans and players stop enjoy going to the home stadium.”

The best recent example of this is Nottingham Forest in 2022-23. In general, teams take the larger percentage of their points at home, but Steve Cooper’s side relied heavily on games at the City Ground to stay up, taking 30 of their 38 points (78.95%) at the ground.

Burnley were another side who capitalised on home advantage in their first season up, taking 33 of 40 points (82.5%) at Turf Moor in 2016-17.

The money – Kieran Maguire

One thing promotion to the Premier League guarantees is money beyond anything possible in the leagues below.

“Between the two times Sheffield United were promoted – in 2007 and 2019 – football inflation, in terms of money coming into the game, went up by 190%,” says Maguire.

“Brentford’s income went from £17m to £142m when they were promoted [in 2020-21].

“It’s a minimum of £100m for going up, plus £75m of parachute payments. If you survive that second season you get three years of parachute payments instead of two.”

The question is how to spend that money? We’ve witnessed all manner of different strategies from promoted clubs, some successful, some not.

“Some have effectively taken an air shot,” adds Maguire. “If we go back to Blackpool when they were promoted hardly any money went into the wage budget.

“When we’ve seen Norwich promoted on at least one occasion again their approach was these are the players who’ve taken us to the Premier League and we’re going to give them an opportunity to prove themselves.

“If that works, that’s fine, but if it doesn’t you have the fans very quickly accusing the board of not being willing to gamble.”

Last season was something of a triumph for splashing the cash on players, with all three promoted clubs staying up after having spent to a significant degree to recruit heavily.

Nottingham Forest took this to the extreme, bringing in 30 players at a combined total of around £168m (according to Transfermarkt). Bournemouth (12 players at £71.8m) and Fulham (13 players at £61.5m) were no slouches either in the market.

The new boys – Luton chief executive Gary Sweet

Luton face a delightful but daunting task this season as they look to mix it in the top flight with England’s elite.

As recently as 2018, the Hatters were playing in League Two, but having beaten the odds already to gain promotion to the Premier League they now have an even greater test to stay there.

As Hatters chief executive Sweet explains, the challenge is a big one, with some unique aspects as a result of their rapid rise, but it is one they are focused on doing the way they feel best serves the club.

“You’re completely and utterly swamped by everything,” he says. “We partied hard one night and at 11 o’clock the next day we were in a recruitment meeting and from then it’s been completely manic.

“A lot of it has been brought on by ourselves. We’ve got an awful lot more to do with our stadium than most clubs coming up [They are having to spend £12-13m updating the stadium to make it ready for the Premier League]. It really is economic gymnastics.

“We rely on process and we’ve done this three times now, getting promoted. While the scales are different moving from one division to another the processes remain the same. Whether the process has an extra nought at the end of the numbers, it’s the same thing.”

According to Transfermarkt, Luton have never spent more than £3m in a single transfer window. That is likely to change this summer, although Sweet is adamant they will not be replicating the lavish outlay of the likes of Forest last season.

“We’re going to be sensible,” he adds. “We got promoted into the Premier League by finishing third having had a bottom-five/six budget anyway. We’re used to being able to manage that value so we’re looking at it as an exciting challenge.

“We firmly believe if a group of players are good enough to get you there they’re generally good enough to keep you there. What we always need to do is top up with a bit of extra quality depending on the division.

“In the Championship, for example, we had to add a bit of extra athleticism. This time we’ve got to add a bit of technical ability.”

Finally… the stats

Only once in Premier League history have all three promoted teams gone straight back down again, in 1997-98 when Barnsley, Bolton and Crystal Palace were relegated.

Last season was the fourth time since 1992-93 that all three promoted sides have avoided the drop – following 2001-02 (Blackburn, Bolton and Fulham), 2011-12 (QPR, Norwich and Swansea) and 2017-18 (Brighton, Huddersfield and Newcastle).

The highest finishes by promoted sides were Newcastle in 1993-94 and Nottingham Forest in 1994-95 who both finished third. The last team to finish in the top five was Ipswich in 2000-01.

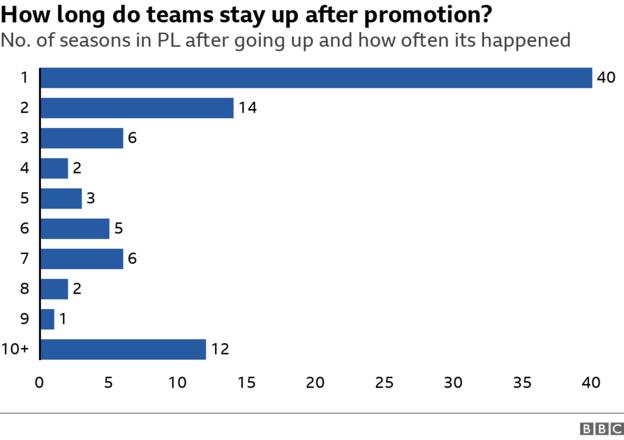

The above graph lays bare how tough it is to survive that first season in the Premier League. On 40 occasions sides have failed to make it past a single top-flight campaign before going back down.

It also adds weight to the ‘second-season syndrome’ theory, with teams relegated after two top-flight seasons on 14 occasions.

The best season for sides coming up and then sticking around was 2001-02, when all three promoted teams stayed in the Premier League for more than a decade – Blackburn and Bolton (both 11) and Fulham (13).