A man who came third in a bicycle race might not seem like a game changer.

But it gives a clue to the very creditable possibility Britain is on the verge of another golden period in a sport in which it has seen immeasurable success across the previous decade.

Hugh Carthy’s hard-fought podium place as a result of some cold mountain passes at the Vuelta a Espana is arguably just as significant as Tao Geoghegan Hart’s glittering victory at the Giro d’Italia for Ineos Grenadiers last month.

The hard yards of EF Pro Cycling’s Carthy were done before Saturday’s climb up to Alto de la Covatilla.

And they were done with fewer team-mates, in a team with a lower budget and with victory on a stage where only a few have triumphed.

All resulting in another relatively young rider forming part of a new Brit pack who are phenomenally good at racing bicycles – and could potentially spend the next decade tearing strips off each other on the most brutal mountain climbs across Europe and beyond.

Shout to the top

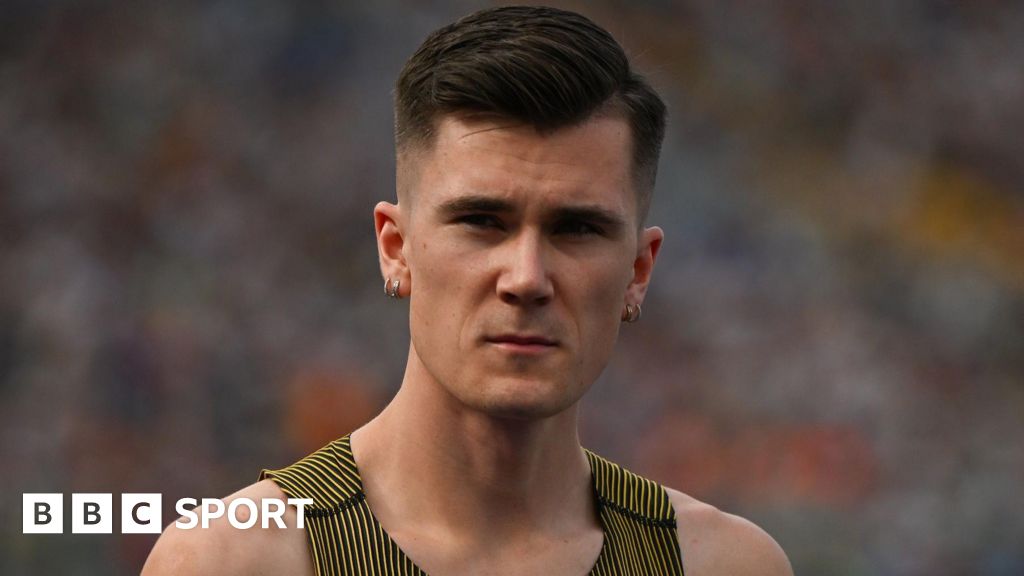

Carthy, 26, may not stand on the very top of the podium on Sunday, after the largely processional stage into Madrid, but he made it to the summit of the race’s most gruelling mountain pass ahead of anyone else six days earlier.

There are strong riders, riders who have their day and special riders who can do things most others cannot.

The Alto de l’Angliru is a famed proving ground for some of the sport’s best – including Alberto Contador, who in 2017 beat eventual Vuelta winner Chris Froome there.

Carthy was patient in the build-up to that moment on stage 12 and, perhaps with an honesty in cycling only a man from Preston could express, had pain etched right across his face as he and his rivals climbed up ascents which included a 17% gradient.

As rare as it is to see an athlete’s pain in a sport where a poker face is said to count for a lot, Carthy’s impassioned yelps as he sped towards the line 26 seconds ahead of expected winner Primoz Roglic revealed a cathartic release.

Prior to Monday’s 109.4km run up to the Angliru from Pola de Laviana, Carthy probably belonged to a group of riders generally accepted as ‘good’ by a peloton which, at times, has more rules for respect among its peers than a prison hierarchy.

Things should be different now. He’s moved up a notch in the bunch’s meticulously-managed pecking order.

He is a Peter Crouch for cycling’s exciting new era, if you will. The 6ft 3in all-rounder has performance and ability that belies his gangly frame – he’s taller than Chris Froome – with a playful tone, who can “pull the tripe out” when required. (A Preston-area term for a big physical effort, given you were most definitely wondering).

And the comparisons don’t end with the physical, given his belated rise to the top has been more round the houses than most, including a spell with Spanish second-tier team Caja Rural, before joining the World Tour with his current team in 2017.

Do it yourself

Overall he lost out to the sport’s strongest team this year, led by the sport’s strongest rider, pound for pound.

Roglic may have lost the Tour de France in unbelievable circumstances to Tadej Pogacar in September, but he and his all-star Jumbo-Visma team were not going to let it slip again this time.

They are the new Ineos when it comes to depth of talent, controlling the pace of the race and the peloton, and made it count during the three-week race mostly across the Basque country, despite losing one of their best support riders Tom Dumoulin.

And what of Ineos? They arrived at the Vuelta with a recovering Chris Froome and Richard Carapaz as their leads – it very quickly becoming clear the latter would be their protected rider, who showed the ability if not the overall team support which could have beaten a determined Roglic, but left him runner-up.

In Milan, Ineos’ Geoghegan Hart won the Giro d’Italia brilliantly, but he did so without triumphing in the Angliru’s equivalent toughest mountain stage in the Italian Alps over the Passo dello Stelvio, despite some tenacious riding with his star time-trial team-mate Rohan Dennis.

Carthy, on the other hand, was not afforded the same degree of support from his spirited team who have far less in financial reserve than Ineos.

EF Pro Cycling exist to upset the apple cart in the sport where they “are in the bottom third” of the budget scale, where the likes of Jumbo-Visma and Ineos reign supreme, according to team boss Jonathan Vaughters.

“The most important part of this team is that we give the underdogs, the overlooked and the guys who haven’t been given their fair share opportunities to win races,” he adds.

“The organisation is about the upset victory and about doing it in a fun, honourable and honest way.”

Carthy fits that mould, and he has had to survive the race’s most brutal moments alone. He couldn’t do it all.

But it says all the more about his achievement that his team could never come to Spain with the intention of fully backing Carthy for victory – as his other, better resourced rivals were.

They have to cut their cloth accordingly, and they did – winning two other stages through Michael Woods and Magnus Cort.

A bright future

2020 has been a season which has seen the lowest numbers of wins by British riders since 2011.

But for those who enjoyed nine years of watching Ineos (formerly Sky) elevating the best of Britain’s cycling talent – such as Bradley Wiggins, Chris Froome and Geraint Thomas – to the top of the sport, the season has turned from a disaster into what appears quite a smooth transitional period. However unintended.

Froome’s loss of form following terrible injury in 2019 and a departure from Ineos which lacked the fanfare it perhaps should have had after protracted contract negotiations, were the catalyst for being overlooked for his beloved Tour de France.

And Geraint Thomas’ poor form and then awful luck in breaking his pelvis in the Giro, and Mark Cavendish’s ever more emotion-driven decline, sealed British Cycling’s woes.

And all after being denied another potentially golden Olympics thanks to the coronavirus.

But hopefully all three will live to fight another day in 2021’s Grand Tours – along with Adam Yates in an Ineos kit, and his brother Simon at Mitchelton-Scott.

Perhaps thrillingly, they will be doing so against those who, as boys, watched their heroes pave the way for them on television years earlier.

Carthy and Geoghegan Hart are just two from a crop of nearly more than 100 British professional male riders of different disciplines looking to break through to the sport’s sharp end.

And it’s not just including Ineos’ endless talent stream, which now has Tom Pidcock alongside Ethan Hayter and Chris Lawless.

Teams overseas have taken note: Harry Tanfield of France’s AG2R LaMondiale, James Knox of Belgium’s Deceuninck-Quick Step and Mark Donovan of Germany’s Sunweb, to name a few.

All they need to do now is pull their tripe out and it’s another 10 years at the top.