In the centre of a small east London park, just a stone’s throw from Leyton Orient’s stadium, is a statue of a man with arms outstretched, his left foot raised delicately on tiptoes.

The football at his boots makes his profession clear, but the posture could be that of a dancer – perhaps even a trapeze artist.

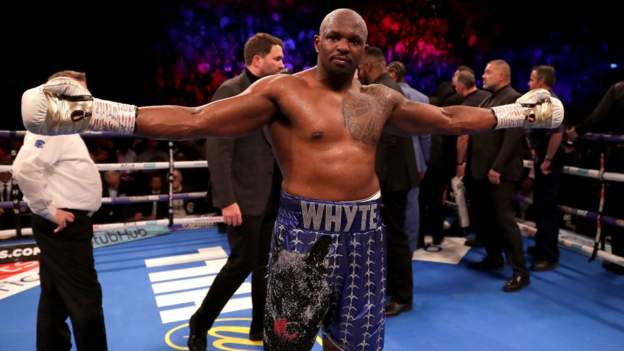

Balletic is one word frequently used to describe Laurie Cunningham, an electric winger who glided effortlessly across the boggy pitches of the 1970s, swaying past defenders with poise and purpose.

Cunningham was the first Briton to join Real Madrid, and one of the very first black players to represent England. He was often subjected to racist abuse.

Those who recall seeing him play talk with a whispered air about greatness. Spain’s former manager Vincente del Bosque, Cunningham’s team-mate at Madrid, described him as “the Cristiano Ronaldo of his era”.

And yet he might have achieved so much more.

Cunningham was an other-worldly talent whose brilliance was checked by injuries and bad luck. He was a pioneer for black footballers who rarely saw himself as a role model. He was a man who moved in extraordinary ways, whose life was sadly cut short by a tragic accident.

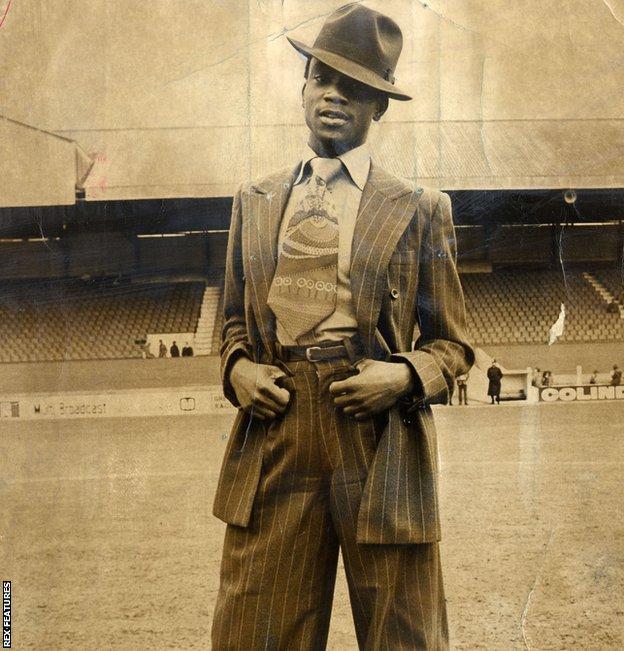

Raised in north London by Jamaica-born parents, Cunningham is often described as being quiet and introverted off the pitch, in contrast to his flamboyant footballing style and love of dancing.

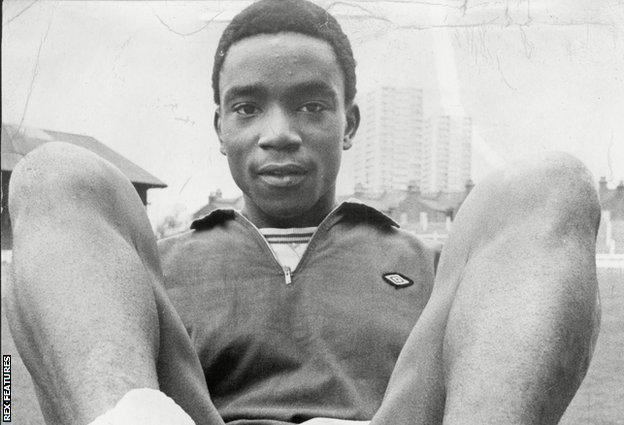

After joining youth side Highgate North Hill in 1968, he quickly established himself as a tremendous talent, but also a boy of grit who could take the agricultural challenges slung his way.

Arsenal showed interest and Cunningham was given a trial, followed by a schoolboy contract in 1970. But the Gunners played a rigid ‘give and go’ style that left little room for Cunningham’s buccaneering gallops. It had just won them the double. He was released in 1972 with the note: ‘Not the right material.’

Cunningham’s prospects hung in the balance. He was picked up by Leyton Orient – then in the second tier, and known just as Orient. His debut came, at the age of 18, on 3 August 1974 in a pre-season friendly against West Ham.

“We lost the game 1-0,” recalls one Orient fan, “but he just ran and ran and ran, dribbling all over Upton Park. He was already a phenomenon.”

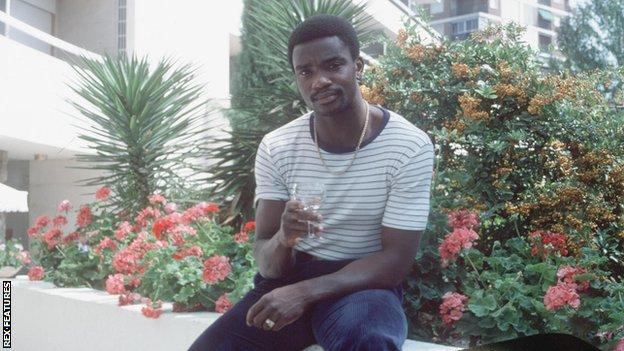

Cunningham stood out off the pitch too; he was a lover of dancing, fashion, painting, architecture and wine. Much of his time away from the game was spent on the dance floor, honing carefully choreographed moves in venues such as Crackers and the Tottenham Royal multiple times a week.

He was a man who moved at his own speed, which could range from the lackadaisical – he was frequently fined by Orient for being late – to the turbo-charged. It was rumoured he’d pay the fines with prize money from dancing contests.

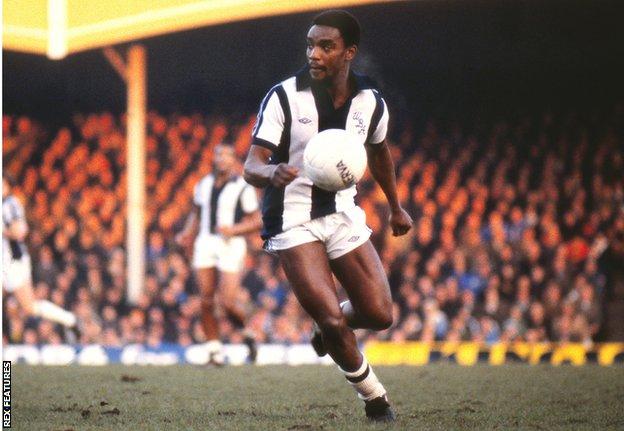

Three years with Orient yielded 75 appearances, 15 goals and a transfer to West Bromwich Albion. There, his talent shone like never before – in often appalling circumstances.

If racism in football still rears its ugly head today, it’s incomparable to what was seen in British stadiums in the 1970s. Bananas, coins and even ball-bearings were hurled at those with black skin. They were regular targets of verbal and physical abuse. In the vast majority of cases, it went entirely unpunished.

Brendon Batson, Cunningham’s team-mate at WBA, explained how the National Front would be waiting for them at away games, where they’d arrive with no security and would be spat on.

Cunningham was regularly the best player on the pitch, a fact that would enrage the abusers even further. He played his game, often slaloming through half the opposing team before bursting the net.

“Defenders like myself were really just there to kick people mostly,” says Viv Anderson, who in 1978 became the first black player to win a senior England cap. “The flair players, like Laurie, got the most stick.”

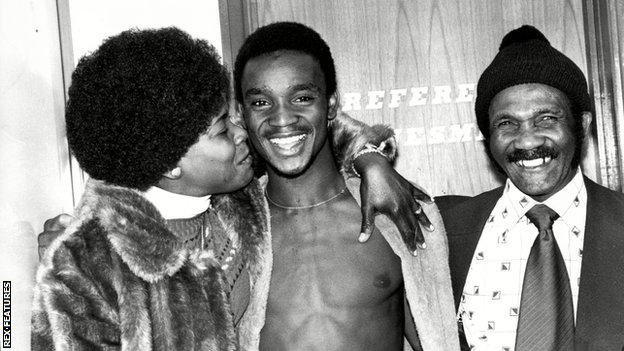

On 27 April 1977, Cunningham pulled on the white shirt of England himself, in an Under-21s friendly against Scotland at Bramall Lane – a game won 1-0 thanks to his goal. He’d go on to play six times for the senior England side.

But his real breakthrough season came in 1978-79, alongside Batson and Cyrille Regis in a scintillating Baggies team that only fell away from title contention in the final weeks of the season to finish third.

This was not the first time three black players had played together in British football, but Batson, Cunningham and Regis were the first to regularly do so. They became known as ‘the Three Degrees’ – a term coined by manager Ron Atkinson in reference to the popular American soul group.

“Everybody sat up and took notice after they beat Manchester United 5-3 at Old Trafford in December 1978,” says Anderson.

“To go there and do what they did, with three black players in the team, everybody just thought: ‘wow.'”

Batson recalls: “There was a whispering campaign about black players at that time, that they were lazy, lacked bottle, didn’t like the cold and couldn’t tackle – which was all rubbish.

“Now black players were coming to the fore. There was a real breakthrough, but it wasn’t a topic of conversation between us at West Brom.

“Maybe at the time, we didn’t realise the real impact we were making outside of our little bubble. But on later reflection we did; we were a visible presence and encouragement for other black players who aspired to make it in professional football.

“I know the black community took great pride in seeing the three of us being successful in the game.”

Cunningham was certainly making an impact. At the end of that 1978-79 season, disagreements over salary led to him sending out letters to Europe’s top clubs stating his availability. He found one already had a keen interest: Real Madrid.

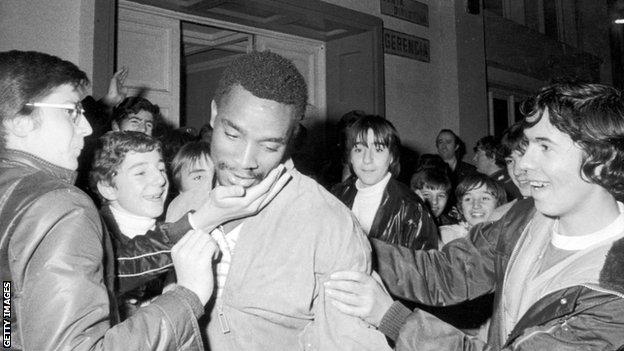

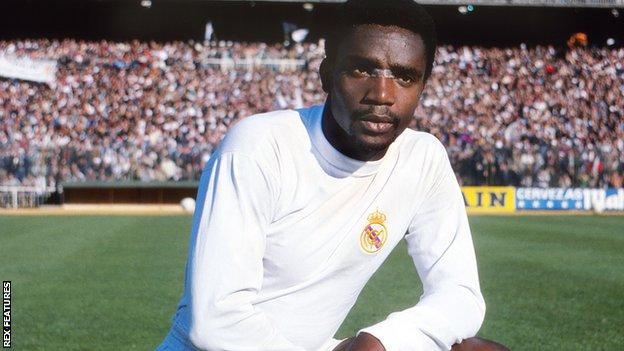

Cunningham became the first British player to join the Spanish side, arriving in a £950,000 deal – a club record for both Albion and Real. There was a feverish excitement that this young man from north London might well be one of the game’s greats.

His arrival at the Bernabeu in 1979 came at a time of great change in Spain. Francisco Franco’s 36-year dictatorship had ended with his death four years earlier and, while the country was experiencing a rapid liberalisation, there were elements of life at Madrid that were slower to change. In Different Class, Dermot Kavanagh’s biography of Cunningham, his then-girlfriend Nikki Hare-Brown, a white woman, says there were tensions over their relationship.

On the pitch, things began well. Cunningham scored on his first appearance against AC Milan in a pre-season friendly, and twice more on his full league debut against Valencia, before the first of a series of injuries put him out for several weeks.

In his first Clasico, on 10 February 1980 at the Nou Camp, he was spectacular. It is a game not remembered for Real’s 2-0 win but rather the extraordinary Englishman on the wing.

“He was electric,” Barcelona defender Migueli recalled years later. “He drove us crazy with his dribbling, his bursts, his speed.”

Even the home support began applauding the man wearing the hated white of Real Madrid. A few months later, they were crowned league champions for a 20th time, adding the Copa del Rey, too.

Injury had limited Cunningham’s involvement, but there had been enough to convince the Real Madrid faithful that he would soon deliver on a regular basis.

Instead, that 1979-80 season would prove to be the pinnacle of his entire career. He was on receiving end of a vicious stamp off the ball by Real Betis’ Francisco Bizcocho in November, effectively ending his 1980-81 campaign. When photographs emerged of him dancing in a nightclub with a plaster cast, the vultures began circling. The newspapers who had so lauded him just nine months earlier now portrayed him as a playboy who didn’t take his talent seriously.

The 1m pesetas fine (worth around £20,000 today) handed down by the Madrid hierarchy was the largest in La Liga history. Cunningham publicly accepted it, but privately he was seething.

Then, after six months out injured, he was frantically rushed back to play in the European Cup Final against Liverpool. One Madrid director reportedly told him his very future at the club rested on his participation.

The game that took place on 27 May 1981, between two of the most illustrious teams in football history, was one of the worst in living memory. The Parc des Princes pitch, which had hosted a rugby match the previous day, provided the turgid setting for a match of few chances and even fewer moments of genuine quality.

Cunningham, clearly unfit and struggling, passed through the 90 minutes like a shadow. He would later describe the game as “horrific”. A well-taken 83rd-minute goal by Alan Kennedy was enough to settle the contest as Madrid missed out on the trophy they craved the most.

The following season saw things sink even further. A challenge during training led to another lengthy lay-off, but it was what happened back in London that brought Cunningham’s footballing struggles into sharp perspective.

Cunningham’s older brother Keith was staying with him in Spain when the pair received news that Keith’s partner and her two children from a previous relationship had been murdered in their apartment – a crime that went unsolved for 28 years.

Madrid officially remained supportive, giving Cunningham compassionate leave to return to England and miss the start of the season, but the writing was on the wall. The arrival of Netherlands international Johnny Metgod, at a time when Spanish teams could only field two outfield players, pushed him further from contention. A painful break-up with his long-term partner left him adrift and those closest to him described a period of great unhappiness.

“At times I thought he needed another year or two years at West Brom, but you don’t turn down Real Madrid,” Batson says. “He was only 23 when he went and I’m not sure he had people around him in the same way.”

A loan move to Manchester United, and a reunion with his old West Brom manager Atkinson, ultimately proved unsuccessful, and when he withdrew from contention for the FA Cup final in 1983, it was clear that Cunningham’s confidence and faith in his own body were rocking.

The following five seasons were a patchwork of loan moves and short contracts that took him to Sporting Gijon, Marseille, Leicester City, Rayo Vallecano and Wimbledon. There were memorable moments along the way, not least the Dons’ improbable FA Cup victory against Liverpool in 1988, in which he came on as a substitute, and Rayo’s dramatic final day promotion to La Liga in 1989. But that mesmeric dribbler with the ferocious pace was never quite the same.

Off the field too, life was tumultuous. Two relationships resulted in two children, only one of whom remained part of his life. A series of failed financial investments and long-standing problems with a house in the hills outside Madrid played out over the backdrop of a football career that was fading much faster than anyone had hoped.

Cunningham’s story ended tragically on 15 July 1989.

Early in the morning, after spending the night at a party at the O Madrid pizzeria, he was driving down La Coruna motorway outside the city with an American, Mark Latty, beside him.

As they approached a roundabout, Cunningham accelerated past a slower car but failed to see another vehicle by the side of the road with a flat tire. Cunningham, who was not wearing his seatbelt, lost control. His car hit a lamppost and flipped several times. Cunningham was taken to hospital but pronounced dead shortly after. He was 33. Latty survived the crash.

A toxicology report would place Cunningham three times over the drink-driving limit. Regis later revealed that they had been involved in a similar accident nearby just a few years before.

“If we hadn’t had our seatbelts on, we would have died,” Regis said.

Most players will never be honoured with a statue outside the stadiums they once graced. Laurie Cunningham has two: the first outside Leyton Orient’s home, the second outside The Hawthorns, alongside Regis, who died aged 59 in 2018, and Batson, now 68.

He is remembered as a footballing ballerina who dazzled with the ball at his feet, while quietly transforming what was possible for black footballers.

“I look at wingers now and I still compare them to Laurie Cunningham,” says Anderson, his former England team-mate. “He could do things other players could only dream of.

“His football was ahead of its time. You look at the pitches he used to play on and the abuse he received… if you put him on a level playing field with everybody else he’d be near the very top.”

Batson adds: “It was tragic what happened to Laurie, but what joy he brought when you saw him play. I think we were all lucky to have seen the best of him.”