“When he crossed the line in Istanbul and ran over to the team, you see the kid that used to enjoy winning.”

From the streets of Stevenage to a seven-time champion of the world – Lewis Hamilton has cemented his status as one of the greatest ever Formula 1 drivers.

Many of the pivotal figures in his journey – such as karting supremo Martin Hines and McLaren duo Ron Dennis and Martin Whitmarsh – are well known.

However if you go back to 1996, a rainy day in Northern Ireland would mark the start of a relationship that would play a significant role in his rise to Formula 1.

Eoin Regan, then a mechanical engineering student from Belfast, remembers the first time he worked with Lewis and his father Anthony before a race weekend at Nutts Corner.

“I was doing work for his engine tuner and he was coming over to Northern Ireland so I was asked to mechanic for him. He won and Anthony asked me to see out that season,” Regan says.

“Everyone was on slicks and it rained in the middle of the practice session. It was his first time there but there was no doubt that he was a class above.

“He worked hard but there was pure talent and confidence in his abilities. That was one thing that stuck with me.”

As Hamilton moved up the karting ranks, Regan was joined on the spanners in 1997 by Jonny Restrick, who was studying in England at the time.

“Lewis was successful but I hadn’t grasped how special he was – you never know until you work with somebody,” he says.

A massive self-belief

Both Regan and Restrick grew up in motorsport and it was quickly evident that Hamilton was much more than an ordinary kid with a big dream.

“He had huge self-belief, and with this exceptional talent there was no one else like it,” says Restrick.

“He once tried an impossible move into the first corner at Fullbeck circuit. It looked like a brain-dead move but the other guys were out of his way by the time he got there. They didn’t know he was coming but he had read it.

“I asked him after how he knew it was going to work, and he said, ‘I don’t know, it just happens’. That’s something you can’t teach.”

Regan says those qualities in karting were evident in his championship-securing race in Turkey, where he came from over a pitstop behind the leaders to win the race by more than 30 seconds in challenging conditions.

“He had the ability to stay out of trouble. He was always there at the end with his relentlessness and never-say-die attitude,” he adds.

“A lot of drivers say they’re unlucky because they get spun off, but Lewis never put himself in that position even in the junior categories with 30 karts.

“He had this natural ability to stay out of trouble and he was a quick thinker.”

The father-son relationship

When Regan joined as Hamilton’s mechanic he was working out of a box trailer on the back of Anthony’s old Vauxhall Cavalier.

He said they would often look after Hamilton at circuits while Anthony worked at the circuit to try and make some extra money.

“It wasn’t all good times. I remember his dad working on computers on a Saturday morning while I got the kart ready,” he says.

“Jonny and I were often landing at the track and looking after him while Tony worked on-site.”

At the circuits, Restrick said the bond between Lewis, Anthony and younger brother Nicolas – who was born with cerebral palsy but has defied the odds to race himself – was clear to see.

“As a unit they were very intense and focused on what they were there for,” he said.

“Anthony was working every hour he could but it’s paid off. It’s a very different world now from the Cavalier and box trailer.”

Regan says the demanding levels set by Lewis and Anthony were matched by the emphasis on loyalty. Despite their working relationship with Hamilton ending as he stepped into car racing, the pair were invited to Lewis’ 21st birthday party as his rise towards Formula 1 continued.

“His family were keen to acknowledge those who had helped him,” he says. “It gave an insight into their values and they had no necessity to do that.”

A life-changing deal

After years of trying to impress Dennis, Hamilton finally got a “sensational” deal with McLaren in 1998.

“At the start, Anthony wasn’t sure if they would have the budget to do the whole season,” says Regan. “When McLaren came on board we were out every weekend, either racing or testing.

“It did bring expectation. In his first year there was a target on his back. It was a great honour and privilege but there’s no doubt people raised their game against him.”

Restrick says McLaren’s involvement was “a step up in the way anyone else went kart racing”.

“We went from working out of a tool van and Anthony’s Cavalier, driving to circuits on Saturday mornings to save on accommodation, to rocking up at McLaren in my 800 quid car to pick up a kitted-out Sprinter van to go to the races.

“Lewis once got a telling off from Ron Dennis because his school report wasn’t good enough. He was miserable because he missed half a test day and we weren’t immediately on the pace.

“It was all part of his education and he was well managed by McLaren on that side of things.”

Restrick, who bought his first mobile phone so Anthony could call him day or night, says Lewis “could be pretty demanding”.

“If he wasn’t happy with the kart it could get heated, but that’s racing and that’s what got him where he is today. He didn’t always agree with us and he didn’t always agree with Anthony.

“There were stressful days but it never lingered. There were times you wanted to go in different directions but ultimately we all wanted to win.”

When Lewis came to stay

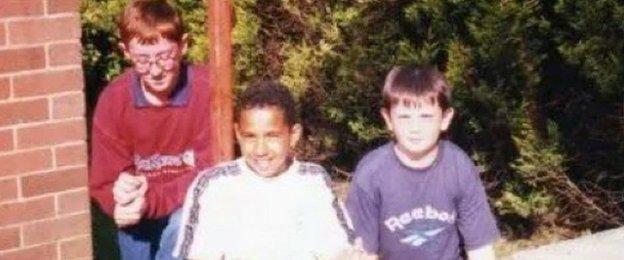

Liam Regan, Eoin’s younger brother, recalls Lewis staying at their family home in Belfast when attending a race meeting at Nutts Corner.

“You couldn’t meet a nicer, more grounded group of people,” says Liam, who is a successful rally driver and navigator.

“When we got back to the house we were busting to play Mario Kart on the Super Nintendo. We must have done 1,000 laps trying to beat each other.

“There was a high level of dedication even at that stage. I remember us all sitting round the kitchen table having a Chinese and pouring over the data from testing. “

After spending four years with Lewis and Anthony, Eoin said the Hamiltons “were part of our family”.

“He was a great kid and full of energy. He loved to mess about,” he said. “Music has always been his passion and he was always playing guitar.”

Restrick added that Lewis was “fun to be around” in his free time.

“We were always in the garden playing football – away from the track it was fun and a good laugh.”

Liam feels that Hamilton’s experiences growing up have shaped the journey of the 35-year-old.

“People overlook his brilliance because they don’t like the way he dresses, they don’t like this and they don’t like that. The Lewis that people see now, there are reasons why he is like that.

“I think in 20 or 30 years’ time people will talk about Lewis the way people talk about Muhammad Ali now. Fighting different causes. Both on the track and off it – we don’t realise what we are watching.”