“I had death threats. I had people who hated me. People told me I was immoral.”

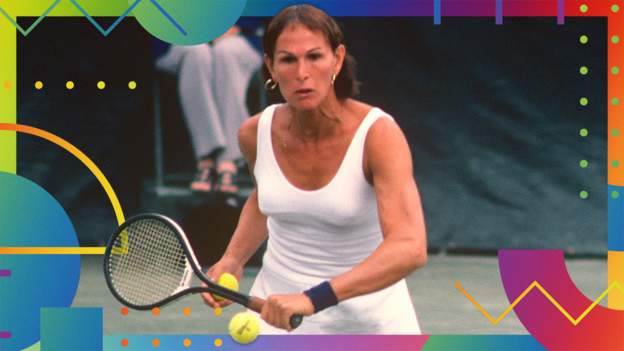

Transgender tennis player Renee Richards was already proving to be a divisive figure when the level of scrutiny surged.

Shortly before the 1977 US Open, the 42-year-old American won a legal battle to compete in the women’s events, leaving her at the centre of a polarising story which made headlines across the world.

“Everybody had a reaction. They were either for her or against her,” says Britain’s Sue Barker, who played against Richards twice in her career and remembers her being booed off court during one of the matches.

“I was a supporter of Renee, I was one of the few in a way.”

The dissent from the sport’s rulemakers, which was backed by several leading players, centred on the belief the 6ft 1in Richards would dominate because of an unfair physical advantage over her rivals.

Others, even aside from those making the threats to her life, were less covert with their objections.

Wherever they were on the sliding scale of disapproval, their bottom line was Richards should not be allowed to play against the likes of Barker, Chrissie Evert and Martina Navratilova.

Richards, who was born in 1934, excelled in a range of sports, got married and started a family.

After graduating from Yale University, the affluent New Yorker trained to be an ophthalmologist, going on to specialise in eye-muscle surgery.

Combining a medical profession with an amateur tennis career, Richards reached the second round of the US Open men’s singles in 1955 and 1957.

“I had a very good and a very full life as Richard. But I had this other side of me which kept emerging,” Richards told the BBC in 2015.

Shaving her legs and wearing skirts while dog-walking allowed her to do what felt natural. But being born a man and living as a woman was not widely accepted in 1960s America, stigmatised and classified as a mental illness.

“I kept pushing back until finally it was not possible to submerge Renee anymore – and Renee won out,” she said.

In 1975, aged 40, she had gender reassignment surgery.

Initially, her plan was to move to California and start afresh in a place where nobody knew her.

But her previous identity was unveiled when she started playing amateur tennis tournaments, leading to a newspaper exposé, more headlines and an insistence from United States Tennis Association (USTA) officials that she could not compete in women’s tournaments.

“I never planned to play professionally as a woman. But when they said ‘you’re not going to be allowed to play’ that changed everything,” said Richards, who is now 86 and living out of the public eye in upstate New York.

“I told them ‘you can’t tell me what I can and can’t do’.

“I was a women and if I wanted to play in the US Open as a woman – I was going to do it.”

To armour their blockade of Richards, the USTA introduced a chromosome test for the women’s players before the 1976 US Open. Richards failed the tests and was barred from entering qualifying.

That led her down the legal route and culminated in a year-long battle for the right to play. The odds were stacked against Richards.

“The USTA had the top lawyers in New York, they brought in witness after witness saying I should not be allowed to play,” she said.

“My lawyer Michael Rosen only had one witness for me.”

That witness proved pivotal. Billie Jean King, who had played doubles with Richards, was a powerful voice after her tireless campaigning for gender and sexual equality.

In an affidavit submitted to the New York State Supreme Court, 12-time individual Grand Slam champion King insisted Richards did “not enjoy physical superiority or strength so as to have an advantage over women competitors in the sport of tennis”.

The judge agreed. Eight days later, Richards was playing in the 1977 US Open.

‘People wondered if it would be a gamechanger’

Tennis had never seen anything like it. Not only did the women’s players now have to take chromosome tests, their preparations for the Grand Slam were disrupted by constant questioning about Richards’ participation in a fervent media storm.

The sport was broadly split into two camps: rejection and a fear she would dominate the game, or acceptance and a show of empathy.

“I was open minded,” Barker, who used to hit with Richards on the practice courts, tells BBC Sport.

“But the ruling frightened a lot of people. They feared she would serve-volley the rest of us off the court and wondered if it would be a gamechanger for the sport.”

Reigning Wimbledon champion Virginia Wade played Richards in the first round but was untroubled in a straightforward victory.

Richards did reach the women’s doubles final alongside Betty Ann Stuart, although they were beaten by top seeds Navratilova and Betty Stove.

Frostiness in the locker room thawed when it became apparent Richards would not offer too much threat. Or, as Richards put it, that she would not “take their money away”.

While she beat some notable names, and climbed into the world’s top 20, Richards lacked the athleticism and mobility of her younger rivals to topple Evert and Navratilova at the summit.

Richards retired aged 47 in 1981 and went on to coach Navratilova to three Grand Slam singles titles.

“It didn’t become the story which a lot of people thought it might become,” says Barker.

“She just melted into the tour and didn’t dominate. She won matches and she lost matches. It didn’t alter the game as some predicted.

“But she achieved what she wanted to do, to play professionally as a woman and was welcomed by the vast majority.”

‘Confrontational’ crowd forced Richards off court and into tears

Hostility and suspicion eventually faded in the locker room, but Richards still faced obstruction and abuse.

She was barred from competing in many tournaments, including Wimbledon and the French Open, where rulebooks said only players whose biological sex was female could play in the women’s events.

This meant most of her appearances came in the United States, travelling around new cities and being made to feel like a circus act as she played in front of a new crowd.

Barker remembers playing Richards in the American’s early days on the women’s tour and says the atmosphere was “confrontational”.

“There were probably about 7,000 people there in this huge arena and she was not well-received by most, if not all, of the crowd,” says Barker.

“It was just horrible. They were shouting things, booing every time she hit the ball and cheering every mistake.”

Despite Barker and the umpire trying to simmer the crowd, tournament officials eventually decided to take them off the court.

The pair were beckoned to a room underneath the stand. Richards started to cry.

“It was really sad and I felt so sorry for her. I told her she didn’t have to put herself through it,” remembers Barker.

“Eventually we went back out but it was clear she wasn’t thinking about the tennis. I think she wanted to just get off the court.

“All she wanted to do was to play tennis.”

Occasionally Richards used to open up to her colleagues, many of whom were curious about her life.

There was a feeling the scrutiny – with Richards later saying she couldn’t “go anywhere in the world without being recognised” – caught her by surprise and took its toll.

“We all admired her courage after the emotional and difficult journey she had been through,” says Barker.

“She used to talk about the emotions she went through and often asked whether she was doing the right thing.

“I’m not sure she realised the impact it was going to have.

“I can’t think of another athlete who has had anywhere near that level of attention. It was an incredibly brave thing to do.”