The oversized snowflakes fell softly and silently, settling among the pines like a picturesque Christmas scene.

By the roadside, spectators in heavy winter coats watched team cars and motorbikes struggle up one of Liege-Bastogne-Liege’s countless climbs, tyres spinning in the slush as they pursued one man on a bike.

It was April 1980 and Bernard Hinault, almost unrecognisable beneath a big red balaclava, slewed doggedly on, further into the lead, somehow remaining balanced on the two wheels beneath him.

He was under such physical strain that he would do himself permanent damage. Pushing his body to its very limit, he raced through the Ardennes in search of victory in the race known as ‘La Doyenne’ – the old lady.

So bad were the conditions that several of cycling’s best riders collected their number from organisers and then never lined up.

After just 70km of the 244km one-day race, 110 of the 174 entrants were already holed up in a hotel by the finish line. Only 21 completed the course. Hinault suffered frostbite.

Rarely do you see such attrition in cycling, but Liege-Bastogne-Liege, which celebrates its 130th birthday on Sunday, has been making and breaking the toughest competitors for years.

Hinault was 25. He had already won the Tour de France twice and would go on to win it a further three times, an icon of his sport in the making. His total of five Tour victories remains a joint record.

But this was a different challenge – a long way from the searing heat and sunflowers of summer.

One of the five prestigious ‘Monument’ one-day races in cycling, Liege-Bastogne-Liege is celebrated by many for being the very antithesis of the Tour.

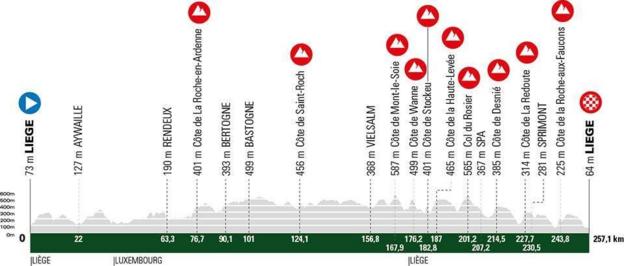

In the hills of east and south Belgium the peloton is stretched through thick, damp forest, over short, sharp climbs and across tricky, part-cobbled sections before landing back where it all began in Liege.

“[The race is] already hard, it’s long, and when I won it was in very tough conditions, especially the snow,” says Hinault, now aged 67.

“Yes, I considered quitting if the weather conditions persisted. We started having difficulties. It’s difficult in Liege-Bastogne-Liege.”

Hinault’s account of one of his greatest triumphs is characteristically taciturn. Tough conditions is a severe understatement. And in the racing he didn’t have it all his own way, either.

With around 91km to go, approaching the 500m Stockeu climb, Rudy Pevenage was two minutes 15 seconds ahead of Hinault and a small chasing group.

Pevenage was one of the hard men of the spring classics. He was a Belgian with a big lead, in conditions many locals would feel only a Belgian could master.

But even he did not finish a race that truly separated the men from the legends. ‘Neige-Bastogne-Neige,’ as it would be dubbed.

On the next climb, a 500m ascent of the Haute Levee, Hinault and a small number of fellow pursuers caught up with Pevenage. Then Hinault launched his attack, bright red balaclava and thick blue gloves disappearing into the distance as his stunning acceleration left everybody behind.

There were still 80km to go.

For just over seven hours Hinault was out there. For much of that time he persisted alone through freezing temperatures. It was brutal, but he would not let up, further distancing his rivals. The persistence in the pursuit of glory came at a price though.

“The sensation of frostbite is that you no longer feel your fingers,” he says. “Today, when it is very cold, my hands get cold very quickly, and my fingers hurt.”

When Hinault came over the line, he was nine minutes and 24 seconds ahead of second-placed Hennie Kuiper, who famously remembers wondering where all the race officials and press were when he arrived.

Their attention was focused fully on Hinault, possibly in disbelief.

Some, such as 11th-placed Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle, don’t even remember crossing the line. Others, who had long since abandoned, only recall that Hinault saluted in the direction of the hotel where they were all congregated – as if they needed reminding who was in charge that day.

But even Hinault must have been surprised at the gap he created?

“Not really, because when I found myself alone, I raced,” says the man known as ‘The Badger’ for his aggressive approach.

“I think that already very young, I had this desire to win. When I found myself in front, I didn’t ask myself any more questions.”

Established in 1892 on the same principle as the Tour de France – to promote a newspaper, L’Express – Liege-Bastogne-Liege rarely fails to test riders. Hinault’s 1980 win is the stuff of legend. But one man has his own statue at the Stockeu climb: Eddy Merckx.

Why him and not Hinault? The Badger won it twice; Merckx five times – more than any other rider. He is, after all, the sport’s most decorated. And he’s Belgian, not French.

Plus, Merckx, now 76, outdid Hinault’s effort by 12km on his most famous victory in 1971. In similarly snowy weather, ‘The Cannibal’ took off from his pursuers with 92km to go, and still had enough energy to outsprint Georges Pintens on the line following the latter’s heroic late comeback.

As this grand old race reaches its milestone of 130 years on Sunday, one rider has one last chance to match Merckx.

Aged 41, Alejandro Valverde was born just one day after Hinault’s 1980 victory. He has won the race himself four times: in 2006, 2008, 2015 and in 2017. That year, victory came the day after his close friend Michele Scarponi died in a training accident.

“It is a very beautiful race,” the Spaniard says.

“All of these races are very beautiful, really any of them, but the year I won after Michele Scarponi was more special.

“I fell in love the first year I took part in 2005. It’s a really hard course, very demanding. I like the atmosphere, and doing monuments is always very special. It suits my characteristics really well.

“Man, I would love to win a fifth time. To achieve that is a great aspiration of mine.”

After its 108th edition on Sunday, Liege-Bastogne-Liege will say farewell to another legend in Valverde. The 2018 world champion and 2009 Vuelta a Espana winner will end his career after the 2022 season.

But the fabric of the race – its roll-call of unlikely winners, its often awful weather, its physical challenges – will endure. Tyler Hamilton, the American rider who retired in 2008, described Liege-Bastogne-Liege as a “cruel, 257km painfest… that some consider to be the hardest single-day race on the calendar”.

It’s also a unique race, one that resolutely remains a reflection of Belgian cycling culture, where thousands of fans of all ages gather, some with a strong Trappist beer in hand.

“Even in the bad conditions people were always by the side of the road,” says Hinault.

“And that’s what’s fantastic about Belgium – it’s that everyone loves cycling.”

Coming from a Frenchman, whose fingers still burn to this day thanks to The Old Lady, that’s quite the compliment.