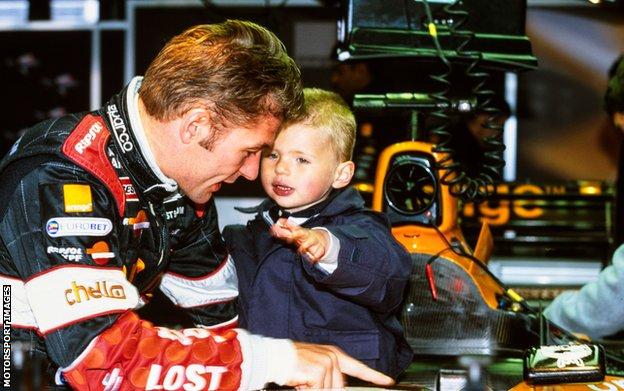

Max Verstappen was two and a half when his parents first realised he might be on the path to being a racing driver.

The boy who became the man who this weekend could end Lewis Hamilton’s reign as Formula 1 world champion was “in the garden every day on a quad bike,” recalls Jos Verstappen, Max’s father, a former grand prix driver who scored two podiums in a career spanning 1994-2003.

“On the second or third day after he got it, he went on two wheels, had to adjust the steering and went side-on into the wall. Luckily, he was wearing a helmet, which got scratched. But he didn’t mind.

“He was driving all the time. He had a feeling with an engine. Didn’t matter whether it was a quad bike, an electric jeep – you know, the small things for children – or whatever. He was always busy with driving. Every day he needed to be on it.”

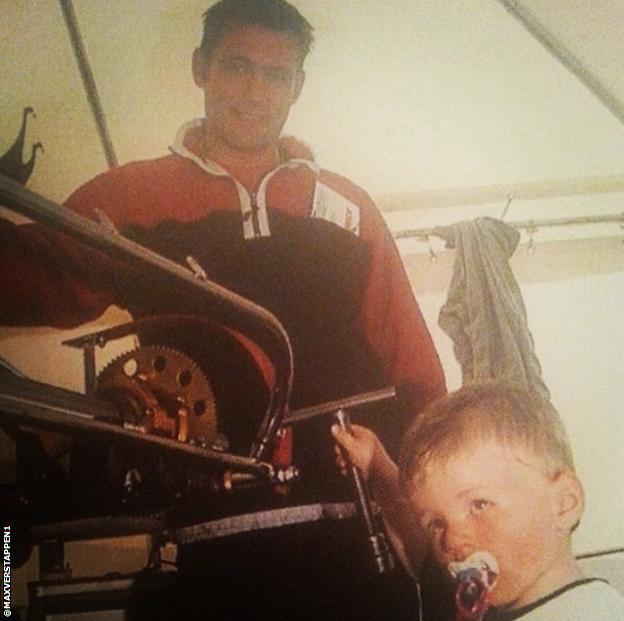

Max, as Jos puts it, “grew up with go-karts”. They were a racing family – his mother Sophie Kumpen is a former top-level karter who as a teenager competed against future F1 drivers Jenson Button, Jan Magnussen, Giancarlo Fisichella and Jarno Trulli.

Jos says: “I didn’t want him to start too early. I wanted to start around six. I think that’s a good age to start – at least they understand a bit better.”

But little Max had other ideas. A couple of years after the garden incident on the quad bike, Jos was away at a race in Canada with his own kart racing team when his phone rang.

Max was at a race track near their home in Genk in Belgium with family members. “He was half-crying,” Jos recalls. “He was four and a half and there were younger people driving and he wanted to drive as well. So that’s when it all started.”

That was 2002. By the end of 2003, Jos’s own F1 career had fizzled out. “After that, I put 100% into his career, really,” he says. “That was my job.”

What follows is a story of love and dedication, ending in the emergence of a driver of incredible capability and talent.

An F1 driver father and an accomplished kart racer for a mother. Max Verstappen – now 24 – was essentially born to be an F1 driver. Once that became clear, his father then effectively programmed him as one, too.

“Without my dad I wouldn’t be sitting here right now,” Max says. “Since he stopped racing in F1, he basically spent all his time preparing me in the best way possible. We grew up together, he was my go-kart mechanic. Driving with the van from Holland or Belgium to all the go-kart races all over Europe.”

After the tears in Genk, Jos bought Max what is known as a baby kart.

“We still have that go-kart,” Jos says. “It is hanging in the Verstappen shop. I remember the first time he got in it. They are not fast, but immediately he was flat-out everywhere and the thing was vibrating so much that the carburettor was falling off all the time.

“So after one day of driving that thing, I bought him a mini-kart, which we had to adjust a lot because he was so small. Then it went better.”

Initially, Jos says, it was more a case of “let’s see what happens”. That quickly became “let’s get to Formula 1”.

“If he didn’t have the talent, I wouldn’t go so deep into it, because go-karts are very expensive if you do it internationally. So we were practising.

“But you could see, compared to all the children of his age, he was definitely a lot further (on) than the others. Also, we were competing against children two or three years older and that makes quite a big difference.”

Max took part in his first kart race when he was seven. His rivals were as old as 11. He won.

“It was tough,” Jos says, “because the tyres were soft (and grippy) and at the end of the race you could see he was tired. But that showed his character, the way he was competing. He didn’t mind if other people were older or whatever, he wanted to win. You could see that was always inside him.”

How ‘deep’ did the Verstappens go into tutoring Max as a future F1 world champion?

“How long have you got?” Jos says. “Let’s say it like this. When he was nine or 10, the next step was the junior category. We went in the winter, from November onwards, every weekend to Italy after school.

“School finished at 2:30pm. I was waiting in the van. He got in the van and I drove to Italy. We would spend two days at all the circuits he needed to drive on and then Sunday afternoon around 5pm I packed up and we drove back. That’s about 1,250km (780 miles) each way. Then in the morning, I dropped him off at school again.

“Italy is where all the competition is, where all the factories are, and I wanted him to learn all the tracks and I wanted to see where we were in terms of speed, in terms of engine, chassis and things like that.

“So I prepared ourselves really well and he loved it. Us two in the van going there. He was sleeping all the time. You see a lot of things happening on the track and on the way you talk about the situations to tell him how it should be – really educational about how to race.

“It was the same here in Genk. Probably two or three times a week we were on the racing circuit and even when it rained, we didn’t care. Even when it was -2C and we had to test something, we went there.

“After five laps, he’d come in, his hands were frozen. I said: “OK, go in the van and warm yourself up.’ And after five minutes I got him out of the van and he had to drive again. It was not always pleasant for him but I think that created his character as well a little bit.

“He saw how much effort I put in and he hasn’t seen anything different and that’s how he is as well. He is very determined and motivated.”

It wasn’t long before Max was making waves in the tight-knit Dutch motor racing community. His father’s name guaranteed attention – Jos was at that point the most successful F1 driver the country had produced – and Max’s results did the rest.

Karting is the arena in which all F1 drivers learn their trade before graduating to single-seater car racing – formula cars. Karts don’t have gears, and drivers sit on them rather than in them, but in all other ways they are like mini racing cars. And Max was a natural.

As the titles piled up, it became very obvious that Max was heading for big things. People began to notice – and to hear about just how much effort his father was putting in.

Frits van Amersfoort is a Dutch racing team owner who ran Max Verstappen in Formula 3 in 2014. It would be his only year in single-seater racing before progressing to F1.

“Together Jos and Sophie built a baby which had the right genes,” Van Amersfoort says, “and then after a while Max was programmed to be a race driver.

“I remember Andre Agassi was built by his father as a tennis robot, by getting 3,000 balls each day around his ears. Jos was like that. In the karting years, as far as I heard, it was sometimes un-human, how the two of them worked together, how Jos prepared and programmed his son to be the best racing driver in the world.”

There were ups and downs, of course. Max was a phenomenon, but he was also just a kid.

Looking back now, he says the singularity of purpose that has been so evident in his F1 career was formed on the karting tracks as a child.

“That’s what counts,” Max says. “That’s how my dad taught me to live. You have to focus on yourself and work with your team. Everything else doesn’t matter.”

It’s easy to say, but is it easy to do?

“After spending a lot of years with my dad, yes.”

How did he do that?

“In a lot of different ways. Nice ways. A bit more angry ways. No, it works for me. I needed it. He made me toughen up, which is good.”

Jos says: “Yeah, sometimes he needed it, absolutely. Sometimes he was not focused and playing and things like that, and when I had that feeling I told him because also I had to develop a lot of things and I went to circuits to test and to find out if it is good. And if he is playing around, I didn’t have the right feedback.”

Did Jos set out to make his son tough?

“I think it’s a little bit how I am, so yes,” he says. “Did I do it deliberately? Probably no, because I’m like that as well.”

By late 2013, Max was 16, and world champion in the highest kart racing category. It was time to move up to car racing.

Jos wanted Max’s first trial in a single-seater to be low-key. He contacted the Anglo-Dutch Manor MP team, and they suggested a private test in their Formula Renault car at Pembrey, a little circuit in south Wales that was occasionally used for junior single-seater races.

Pembrey has been developed since, but back then it did not even have pit garages.

“I think they were quite shocked,” says Manor MP team manager Tony Shaw, who ran the day, “to arrive and just find a track and some sheep and a scrutineering bay.”

The Verstappens had booked two days and on the first day it was raining.

“Jos wanted to delay letting Max out,” Shaw says. “He didn’t really want to let him straight out in the rain. He wanted to let it dry up. But we were like, ‘No, let’s just get out and get on with it.’

“He was really nervous, I have to say, and you don’t expect that of someone like Jos Verstappen, but he was pacing around all over the place.”

He needn’t have worried.

“Max was absolute dynamite right from the off,” Shaw says. “A pleasure to work with. We were like, ‘Is this really his first test?’ But he was really in control, really, really quick; completely natural without any bother whatsoever.”

Manor, as it happens, also gave Hamilton his first run in a racing car, in 2001. The circumstances were different. Where Verstappen had a track to himself, Hamilton was at a group test, with all manner of other cars around of varying performance levels, and the test was at Mallory Park, another tiny circuit, in Leicestershire, not so far away from the UK’s motorsport hub.

“When Lewis drove we were a little bit worried because there were lots of other cars on track and he seemed more eager,” Shaw says.

“Within 10, 15, 20 laps, he’d a had a bit of a shunt and ripped a corner off. He demonstrated a different way of not being afraid of it, by grabbing hold of it and throwing the thing around, whereas Max was fast but much more controlled. And he didn’t really make any mistakes.

“We just thought: ‘Wow.’ He was truly impressive. Max was definitely one that you knew was going to shine. With both of them you knew straight away.”

Verstappen did a few more Formula Renault tests over that autumn and winter, and was quick everywhere. Jos and their manager Raymond van Beuren decided they could skip that category and go straight for Formula 3.

It was a bold move. F3 is a technical, sophisticated category that uses what are effectively scaled-down F1 cars. It is normally very much not for beginners. But then Max was very much not normal.

The Verstappens approached Van Amersfoort, who they knew of old. Jos, who was a prodigy himself back in the day, had raced for his team in 1992 in Formula Opel Lotus in his own first year of car racing, before moving on to F3 in 1993 and then making the jump to F1 with Benetton as Michael Schumacher’s team-mate in 1994.

The idea was to compete in the European Formula 3 championship.

“We were running out of time,” Van Amersfoort says. “It was already February before it was decided. We ordered a car but Dallara couldn’t deliver it. So we borrowed a chassis. We built a car around it, did one run-out in Most in the Czech Republic and then went to the first official test in Budapest.

“Max was quickest from the first hour on. That’s a Verstappen. They keep amazing you. Any Verstappen, whether it’s Jos or Max, they will always astonish you with what they can do. Their drive to be fast is so phenomenal, so intense.

“It sounds a bit weird, but after one day inside the team, we said to each other: ‘We could put Max in an F1 car tomorrow.’ After one day. That’s the truth.”

Max won 10 races that year, one more than Esteban Ocon, but lost the title to the Frenchman – himself now also an F1 driver – largely because of an engine failure at a race towards the end of the season. The punishment for it was 10-place grid penalties at three separate races.

Verstappen’s performance was a revelation. Soon, both the Mercedes and Red Bull F1 teams were expressing interest in signing him. By August, Verstappen had joined the Red Bull driver programme. Shortly afterwards, before he had even driven an F1 car, they signed him to race for their Toro Rosso junior team in F1 in 2015.

In September, Verstappen had his first proper run in an F1 car and earned the licence he needed to drive at a grand prix weekend for the first time. He took part in the first practice session at the Japanese Grand Prix. And in 2015, he became the youngest ever F1 driver at 17 years and 166 days.

Fourteen months after that, he was promoted to the Red Bull senior team after four races of the 2016 season. He won on his debut at the 2016 Spanish Grand Prix.

It is hard to explain to someone not fully versed in motor racing how extraordinary it is for a driver to come straight out of karting into a complex category like F3, with downforce and all the complications that brings, and take to it like he has been doing it all his life.

Drivers are meant to go step-by-step through the junior categories. F3 would normally be the second or more likely third category they do, and many drivers spend more than one year in each category. Only the special ones need just one year in each, never mind just one in anything, before reaching F1.

“It’s only possible when you have an extraordinary driver,” Van Amersfoort says, “and we felt from the beginning that Max was like that. And again, I can’t repeat it enough, with the knowledge of Jos.

“We’re not talking about a simple driver coach. Jos was everything, and we accepted that from the beginning. We knew our skills as a team were maybe less than the skills of the Verstappens together. But combined we made it into a success.

“And we had discussions. We nearly had fights. But altogether, the year was tremendous.”

The 2014 F3 season was a success, but a demanding one for Van Amersfoort.

“The story is that the Verstappen family is not easy to work with,” he says. “They have high expectations. They don’t settle for second, they don’t settle for a learning year. They just want to be there from the beginning. They go for the best and nothing else.”

To illustrate Max’s determination and single-mindedness, Van Amersfoort recalls an incident at the end of that year.

As has become traditional, the F3 season ended with a race in Macau in China, where all the leading drivers from the various championships compete together on a fast and dangerous street circuit that is held in admiration and awe by drivers around the world.

Macau is characterised by a long pit straight, on which slipstreaming is a key part of racing, and a tight and demanding back part of the circuit, as the cars twist and turn through the city’s hills. As a track, it’s like Monaco but more difficult and much faster. Macau is also notorious for crashes at the first corner of the race.

Max should have won Macau. He was running second in the qualifying race, which would have been the perfect place to start the main event, as he could slipstream the pole position car down to the first corner. But his determination to win overcame logic.

“Max was P2 in the qualifying race but he didn’t give up,” Van Amersfoort says. “He crashed the bloody car trying to win pole. That’s Max.

“Then in the feature race on Sunday, there was a pile-up, like usual in Macau, and Max’s car was badly damaged. The only way to continue was to get back to the starting grid, but all the marshals told him to get out because they wanted to tow it away.

“He refused to get out. He stayed in the car and there he was, hanging from a crane as they lifted it free of the crash. As soon as they put him back on the track, he drove back on three wheels to the grid and we were able to repair the car. He ended up finishing seventh from the back.

“This incredible drive, this incredible internal will to win, I haven’t seen anything like that before, and I’ve seen a lot of race drivers.”

Throughout Verstappen’s F1 career, that will to win has been very clear, partly from his manner out of the car, his straightforwardness, his absolute singularity of purpose. But also from the way he drives.

Verstappen takes aggression to the extreme, something that has become one of the defining aspects of his battle with Hamilton this year. He just will not back down in a wheel-to-wheel fight, even when other drivers would, because racing ethics say they should.

If he’s on the inside, he will push the other driver wide; if he’s on the outside, he will turn in on them and compete, regardless of whether standard practice would dictate they have won the corner, and he should really concede. That’s how he races.

Jos says he “doesn’t know” where Max developed that style. “He did it in go-karts,” he says, “so I don’t see anything different. When he sees the gap, when he has that feeling he can overtake, he will go for it.”

But Van Amersfoort says: “Jos was driving like that, too. That comes from Jos. We had so many visits to the stewards in the F3 year and it was always the same. A Verstappen can’t lose. They can’t bear the fact that they have lost.”

Red Bull team principal Christian Horner, who raced against Verstappen’s mother in karting, agrees: “That came from his dad. His mum was a smart racer. He’s got the aggression of his dad and the racing head of his mum.”

If that approach was passed down from father to son, though, not everything was.

Van Amersfoort says: “Max has the rough side of Jos, and the racing skills, but he has the social sides of his mother. Max as a human being is completely in the middle of his father and his mother.

“If he was too kind, or maybe a bit too much of Sophie, he would not be such a good racer. If he would be too much like Jos, he would be the same sort of race driver as Jos and in the end there would have been tears. But he is exactly in the middle.”

Max is Jos’ son. Jos guided him to become the driver he is. But he’s not Jos.

Max can be short with people. And there is a roughness about him that sometimes comes out – in 2018, after he had had incidents in all the first six races of the season, he said he “might headbutt someone” if journalists kept asking him why.

But as a character, he differs from his father.

“He’s always been relaxed when I put pressure on him,” Jos says. “He was like: ‘OK, it will be fine, don’t worry.’ And he’s like that now.”

Max says: “My dad sometimes was a bit worried that I couldn’t be bothered or I was too relaxed, but I said: ‘Dad, don’t worry. This is just the way I like it and how I approach to get into a race weekend or, like, my zone.’

“Up until F1, he was still worried about it, but he also could see that he couldn’t affect that bit of my preparation. Still nowadays my dad is more excited about starting the F1 weekend than I am. I get sent so many things, my dad asking questions about the weekend, and I am like: ‘I will find out when I get to the track.'”

Max gave this answer in an interview this summer. I mentioned it to Jos.

“He doesn’t feel the pressure, that’s the thing,” Jos says. “He doesn’t even think about it.

“He thinks: ‘If my car is fast enough to win a championship, I’ll win the championship. If not, I will finish second.’

“Everybody sees – and you see it as well – how talented he is. And all the teams in the paddock want Max at the end of the day. And that makes us comfortable as well.”

Back home in the Netherlands, Max has become a sensation. For some years now, races held in central Europe – in Belgium, in Austria, in Hungary – have been mobbed by Dutch fans, all wearing T-shirts in the national colour of orange, all supporting Verstappen with a fervour that matches, at least, that shown for Ferrari in Italy.

This year, the Dutch Grand Prix returned to the calendar as the historic seaside resort of Zandvoort held a race for the first time since 1985. It did so because the Dutch organisers and F1 itself wanted to cash in on the Verstappen phenomenon. It was a roaring success.

For four days, there was essentially a national party in honour of Verstappen. The little holiday town was festooned with Verstappen banners. Grandstands were packed with as many spectators as the authorities would allow in the context of the pandemic. At the track, house music played from morning to night. The fans chanted their support for Verstappen, let off orange flares. And he repaid them with a pole position and a dominant victory.

“The enthusiasm of the Dutch people for Max is incredible,” Van Amersfoort says. “Five years ago, the whole Dutch community was behind our national football team. All these people now are behind Max. They forgot about football.”

Why did he cause such a reaction?

“We Dutch,” Van Amersfoort says, “we don’t like the polished world champion. We like the raw guy fighting for it. We like the bull fighters. And the Verstappens are like that.”