One morning, some time around 2010, the deputy head teacher of Davenant Foundation School in Essex stood to give an assembly.

The chosen subject: the middle-distance rivalry between Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett.

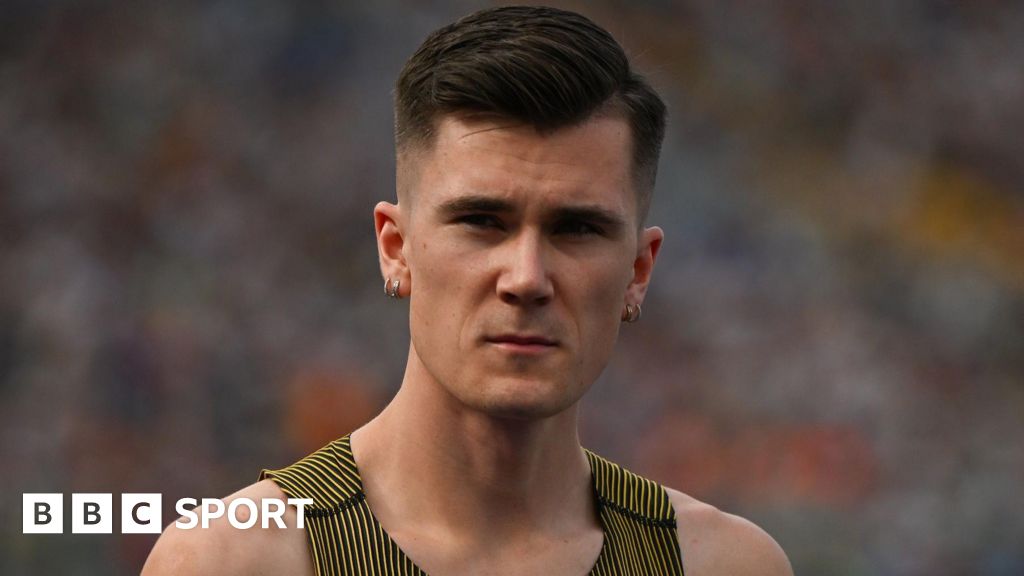

In the audience was a 13-year-old Daniel Rowden.

“I thought it was incredible,” he remembers. “The hype that surrounded them. Such different characters, such an intense rivalry and such fantastic performances.

“The whole nation had their favourite, either Coe or Ovett, and were talking about it in the streets.”

Quietly, Rowden has now joined that tradition.

Earlier this month, in Zagreb, Rowden ended his season with an 800m victory in one minute 44.09 seconds.

The 23-year-old’s time put him joint-ninth on the British all-time list, level with 1980 Olympic champion Ovett.

Rowden sees it a little differently to how most might. It is his name up there, but not him. Not exclusively anyway.

“Most of my athletic performance is down to my genetics, which I have no control over,” he says.

“Then there are the opportunities that I was given as a kid, to have a running club down the road with good coaches and training partners – none of that was under my control.

“If other people had the same skillset and opportunities they may even run better than I do. I can pat myself on the back if I train hard or ran well, but, a lot of the time, it is not down to me.”

Rowden’s outlook comes from a Christian faith that keeps sport in strict perspective.

“For some athletes, athletics is everything and their whole level of success as a person revolves around their performances,” he says.

“For me, my faith and how God views me is so much bigger.”

From 1924 Olympic champion and Chariots of Fire inspiration Eric Liddell to Doha 2019 triple-jumper and content-creator Naomi Ogbeta, strong faith has often coincided with strong performances for British athletes down the years.

For Rowden, there are tangible reasons why.

In Zagreb, before his new personal best, he didn’t want to run.

“An hour or so before the gun, I just couldn’t focus,” he says. “I was more nervous than I had been for the whole of this season. But I remembered, at the end of the day, God is in control. I live my life to please him. If I just give my best that will be fine.

“It was a huge boost to calming nerves and getting me ready to run well. “

Eighteen months before, Rowden had been more concerned with relearning how to get out of bed.

For years, he had suffered from sporadic bouts of intense post-training stomach pain. He would lie down waiting for them to pass. The doctors suggested irritable bowel syndrome, vitamin D deficiency or an intolerance to dairy products. And nothing got better.

Finally he was diagnosed with Mals (median arcuate ligament syndrome), a rare condition where the diaphragm muscles squeeze too tightly around an artery, restricting the flow of blood and oxygen to the gut.

Rowden was given a choice. There was an operation that would involve slicing open his stomach to fix the artery, which would leave him wincing with pain at the most basic movement and his digestive system twitchy at the most innocuous foodstuff.

Or he could, as the surgeon put it, “avoid intense exercise”.

“It wasn’t a close call at all,” remembers Rowden. “It never crossed my mind not to have it done.”

So, he would roll out of his bed at London’s Charing Cross hospital, carefully avoiding straining his surgical wound, before gradually increasing his laps of the corridors and stairways.

Eating was even harder. Rowden would lie sleepless in bed as his body mulled over whatever he had chosen for dinner.

“There was one time I ordered a pizza. I ate it all and it completely ruined me. I brought it straight back up,” Rowden remembers. “After that I was a little more cautious.”

He can eat whatever he wants now, the stomach pain is almost entirely gone and he has a new focus.

Two years into the course, he is putting on hold his mechanical engineering degree at London’s prestigious Imperial College to concentrate on Tokyo.

First, he will have to come through a fiercely competitive British scene that includes Elliot Giles, Kyle Langford and teenage sensation Max Burgin.

If he does, he can set his sights on world champion Donavan Brazier.

The American is just five months older than Rowden and a presence he has been aware of since they were teenagers.

“I remember when he ran the US collegiate record in 2016 and noticing we were both born in the same year,” says Rowden.

“He was supposed to be at my World Junior Championships in Poland later that year before he decided to try and qualify for Rio instead.

“He is an incredible talent – strong, fast, probably the best 800m runner in the world. He is someone I benchmark against to a degree.”

All that can wait though. Rowden is now looking forward to winding down from an impressive 2020 comeback season with a family break on the Kent coast and three days on his own in Dorset.

“It will be a complete switch-off and a reset,” he says of the latter.

“I will go walking, sleep a lot, pray, have some time of solitude and silence to process this season and give my mind a rest.”

On his own, but, as Rowden stresses, nothing he does is truly alone.