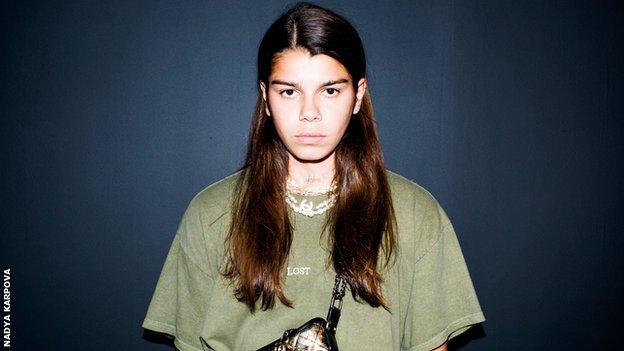

Nadya Karpova’s full first name – Nadezhda – means ‘hope’ in Russian. She has a small tattoo with the word in English on the front of her neck. She had it done when she was 21, but doesn’t even remember what hopes she had at that time. Now it has real significance.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in the early hours of 24 February, only a small number of Russian sportspeople have spoken out against it.

Among the country’s current international footballers, just three have done so.

From the Russian men’s team, Dynamo Moscow’s Fedor Smolov posted a ‘No war!’ message on Instagram in February. He has been silent since. Aleksandr Sobolev from Spartak Moscow also posted a message on the day the war started but deleted it a few hours later.

Karpova, who plays club football for Espanyol in Spain, is the third. She is the only member of the Russian women’s team to have voiced her opposition, and she does so almost every day. Since the war started, more than three months ago, she has been posting anti-war messages on Instagram, where she has 143,000 followers.

“I can’t just look at this inhumanity and stay silent,” she says. “I don’t know what would happen if I was in Russia, not in Spain, but I feel a special responsibility to speak out.”

Our interview takes place in Barcelona, where the 27-year-old lives, having moved to Spain in 2017. She has played 24 times for Russia, including at the last European Championship, five years ago. The next are just around the corner – in England from 6-31 July – but the Russian team won’t be there. They are banned – a result of the country’s invasion of Ukraine.

Meeting at a Chinese restaurant, she doesn’t touch her food once we start talking about Ukraine. She’d arrived early, hungry, and ordered hotpot; a broth that’s placed on to a small stove burner built into the table. Diners finish the dish themselves – adding vegetables, meat and noodles.

While we are talking, the broth starts to bubble, then boil away. Karpova doesn’t even look at it.

She is careful with her words. But it is not that she is trying to censor herself – even though a new Russian law can lead to up to 15 years in jail for spreading anything the authorities consider to be ‘fake news’ about the military.

She isn’t afraid to say something wrong, as is common among Russian athletes. Instead she is afraid of forgetting something important. And she is also trying hard not to speak only in swear words. The longer the interview goes on, the less careful she becomes.

“Russian propaganda is trying to persuade Russians that we are a very special nation and the whole world is against us and our ‘unique mission’,” she says.

“What unique mission are you talking about? I don’t think that Russians are special. At the same time, I am not ashamed to be Russian, as Russia doesn’t mean the government and Vladimir Putin.

“Putin took everything from us, he took our future. At the same time, he did it with our tacit consent. They [the government], didn’t witness strong resistance. Most people were just closing their eyes to injustice, thinking it’s not their business.

“I took part in two opposition rallies, the last one in support of [the main Russian opposition figure Alexei] Navalny when he was poisoned and imprisoned, but still, I don’t think that I’ve done enough.

“These people who justify the war, they are hostages to propaganda. I feel sorry for them, and I believe we need to do everything to release them from it.”

Karpova was 22 when she arrived in Spain. Valencia had seen enough to offer her a contract after Euro 2017, even though she only made three substitute appearances as Russia failed to reach the knockout stage in the Netherlands.

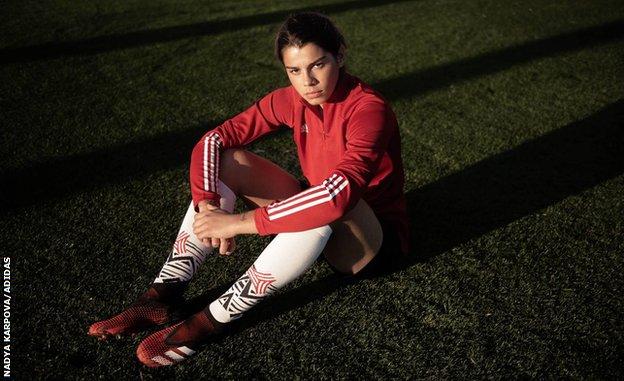

A year earlier she’d been ‘Backed by Lionel Messi’ – the only female among nine young footballers from all over the world chosen to feature alongside the Argentine in an Adidas advertisement campaign.

Karpova’s main motivation for relocation was mainly the level of women’s football. The weather was a factor too – it is not much fun to play football in winter in Russia. But after moving to Spain, something fundamental changed within her.

“I stopped being afraid of certain things, for instance to speak out,” she says. “I also understood that no one would blame me for living with a girl and that there is no stigma here for being a lesbian.

“Your coach can ask you here: ‘Will your girlfriend come to a game?’ I just thought wow. In Russia, people only ask if you have a boyfriend, here they say ‘partner’ – ‘pareja’.

Since childhood, Karpova had been trying to hide her homosexuality, or least not to talk about it publicly. She tells a story about talks over her first professional contract.

The owner of the club, Rossiyanka, was trying to persuade her father to sign, promising that they would “look after your daughter, a lesbian”.

Karpova says: “According to these people, lesbians needed special treatment. I was 18 then. My dad told this guy to… go away. He said that he was ready to discuss only football, not my sexual orientation.

“The difference between here and Russia, as an LGBT person, was huge.”

In 2013, the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ among minors was made illegal in Russia under a new law supporters said was designed to protect so-called “traditional Russian values”.

There are no openly gay national team athletes in Russia. Karpova has never spoken publicly about her sexuality before. She even only told her mother a year ago.

“It’s not a secret to anybody that the main problem of gay kids is that you are always in the closet,” she says. “You are afraid to be judged by society. And when your state becomes the one who bullies you, it’s just absurd.

“Now Russian propaganda is trying to discredit people who speak out against the war, by outing them.

“For instance, when Margarita Simonyan [editor-in-chief of state media outlet RT], was talking about [comedian and presenter] Maxim Galkin’s anti-war position, she said: ‘He is actually gay!’ Like being gay means that you are a bad, disgusting person with no moral values.”

In March, Karpova was joined at Espanyol by fellow striker Tamila Khimych, who is Ukrainian.

“When I first met with her, she looked at me cautiously,” Karpova says. “Like she was not sure if I was pro-war and considered Ukrainians enemies.

“I wanted to cry. I was thinking about her family and friends, and if they are OK. It was such a horrible feeling to understand that she could lose loved ones.

“I’m just overwhelmed with emotions. I still can’t believe sometimes that it is real, and it is happening.”

Karpova was very glad to learn that her new team-mate’s relatives are safe. But thousands have been killed, a lot of Ukrainians are still in danger as the war continues, and no one knows when it will end.

She admits that she is very glad that her current job is not connected to the Russian state in any way – in contrast to most professional Russian athletes. She thinks that it will probably be wise to skip a trip to Russia to visit her parents and friends this summer.

But still, she hopes for change.

“I wish more and more Russians – Russian athletes too – would speak out so other people who are against the war know that they are not a minority,” she says.

“You can’t just pretend that nothing is happening, not any more. The time of silence should be over.

“They [this government] will go away one day, they are all old. When this happens, we will still be alive, and we should be ready to sort everything out.

“I hope it will happen very soon.”