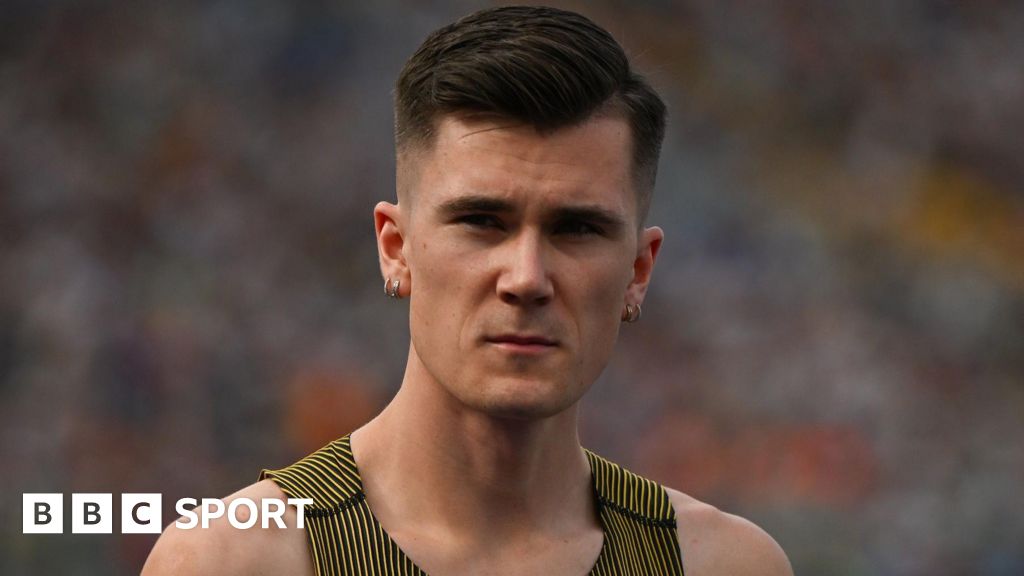

Just over a year ago Adam Peaty was asked the question that would shape the next period of his life.

“What do you want to do?” his coach said. Did he want to do it all again?

“In the moment I wanted to just stop. Stop everything,” Peaty tells BBC Sport.

“I didn’t even want to see a pool again. I had been beaten down again and again and again.”

During the previous nine years Peaty had won two Olympic gold medals, becoming the first British swimmer to retain an Olympic title in the process.

For eight of those years he had been invincible in the pool – a remarkable unbeaten run in the 100m breaststroke where he broke the world record five times – and a star out of it, dancing into the British public’s living room every Saturday night in glitter and sequins.

In 2022 and 2023, however, everything had been different.

“It all came crashing down. I came crashing down,” he says.

“I didn’t take a break after the Olympics in 2021.

“I went straight into work, did a bit of dancing because I thought it’d be the right distraction and I broke my foot later that year.

“That led me into 2023 and having a major, major burnout.”

Peaty’s broken foot meant he missed the 2022 World Championships and went into the Commonwealth Games undercooked.

There he finished only fourth in the final, his winning run in the 100m over.

“When I lost that 100m final I spiralled,” he says. “I went quite aggressive. It is an Adam I don’t really recognise.

“I went to Melbourne [for the short course World Championships four months later] and I blew up there because I didn’t get the result I wanted.

“I was kind of pointing fingers. I didn’t really have the maturity to kind of get over that. I pretty much lost control of the whole ship.”

Peaty spoke about problems with depression and alcohol following his victory at the Rio Olympics in 2016.

Those issues worsened, his relationship with the mother of his son, George, broke down and after continuing to compete in early 2023, he eventually opted to take a break from the sport altogether, citing mental health reasons.

He said publicly he was in a “self-destructive spiral”.

“At my lowest I was in a place that I couldn’t even look at my myself in the mirror – couldn’t even process what I wanted to do in a day,” he says.

“Everything seemed grey. There was no colour, no optimism, no healthy relationship with the people that want you to be better.”