| Venue: Stade Pierre-Mauroy, Lille Date: Saturday, 23 September Kick-off: 16:45 BST |

| Coverage: Listen to BBC Radio 5 Live commentary of the first half and follow score updates during the second half; listen to uninterrupted radio commentary and follow live text on the BBC Sport website and app |

It takes a big man to sit Danny Grewcock on the seat of his shorts.

Pablo Lemoine was, and is, a big man.

Back in 2003, weighing just shy of 20st, the Uruguayan prop took a pass, revved the diesel engine, dipped his shoulder and ploughed through Grewcock and over the England line.

It was Uruguay’s only try in a 111-13 pool-stage defeat by that Rugby World Cup’s eventual winners. It remains England’s biggest win at the tournament.

Twenty years on, Lemoine is Chile’s head coach as they prepare to play England in Lille on Saturday.

“You have to enjoy it, because it is surely the most important game in Chile’s history,” Lemoine said on Thursday.

It may well be more enjoyable than that first meeting with England.

This England do not have the same strength in depth or certainty as 20 years ago.

Back then Clive Woodward came into the tournament with settled partnerships practically carved into the teamsheet: Dawson-Wilkinson, Tindall-Greenwood, Johnson-Kay.

His team for the 2003 Uruguay game, which contained none of the above, was strong, but definitely second string.

Steve Borthwick doesn’t have the same luxury. He is still shuffling the pack and backs on the fly. His hope is that, without the time to gradually shape his team since taking the job in January, he will hit on a combination by sudden alchemy instead.

Chile, the weakest team in Pool D, is a chance to test a range of options.

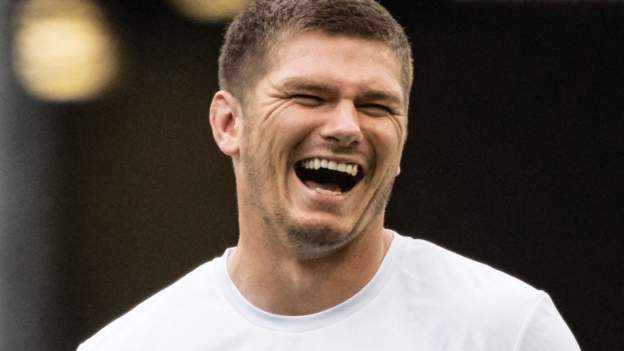

Owen Farrell is one of those in the mix. The England captain has spent matchdays in the stands so far at the Rugby World Cup, serving out the second half of a four-match ban.

Despite being picked at fly-half, Farrell’s likeliest route back into Borthwick’s first-choice XV still appears to be to convince the coach that his game-reading ability and bar-raising standards trump the power and pace of Manu Tuilagi and Joe Marchant’s midfield partnership.

Borthwick doesn’t sound like he will need much convincing. In Thursday’s press conference, the coach interjected after Farrell answered a straightforward question about the view from the expensive seats.

“If I may, can I jump in there?” Borthwick began.

“I have had the opportunity to work with Owen previously and have come back now a few years later.

“The skill and influence he has over others is incredible.

“I see the way he has harnessed the senior leaders within this group, the way he has helped the younger players and they look up to him. He is a mentor and a great voice for myself and the coaching team. I think it is an incredible skill.”

After South Africa’s positional wildcards so far in the tournament – playing four scrum-halves against Romania, carrying only one specialist hooker in the squad, opting for seven forwards on the bench against Ireland – Borthwick has played a joker of his own.

With 144 starts at fly-half for Harlequins and England, and zero in any other position, Marcus Smith has been deployed at 15.

The 24-year-old has added some razzle-dazzle in star turns off the bench, but shining amid broken field and broken bodies is one thing, taking on the responsibilities from the start is another.

Chile will need only a cursory look at England to note that Smith, at 5ft 9in, won’t own the air like 6ft 5in Freddie Steward.

England are gambling that their opponents will be too preoccupied in defence to exploit that obvious vulnerability.

Ollie Lawrence and Elliot Daly in midfield and Henry Arundell and Max Malins on the wings is an enticing mix of speed and silken play-making skills.

Billy Vunipola will try to dominate the gain-line and earn the chance to do so against superior opposition.

And, after the sweat and salt of the Cote d’Azur, Lille’s cooler, drier conditions erase one excuse for England’s poor handling in their first two games.

But those hoping for a scoreline to rival the 98-point winning margin from Lemoine’s playing days will be disappointed.

Chile are a different team. And this is a different era.

As Uruguay and Portugal have shown, this tournament’s minnows are strong enough to hold back landslides.

Back in 2003, less than a decade after professionalism, the gap between the best, newly flush with knowledge and time, as well as cash, and the rest stretched to a chasm.

While Lamoine was playing his club rugby at Parisian powerhouse Stade Francais, most of his team-mates were throw-back amateurs, turning out for different country-club teams from Montevideo’s posh suburbs.

His Chile team now are a professional, unified outfit. Thirty of their 33-man squad play for the same team – Selknam, the country’s Santiago-based representatives in South America’s continental club competition.

Individually most of Chile’s players may not have the quality to earn contracts in Europe, but they turn that into a collective strength, exploiting the togetherness and cohesion more prosperous nations lack.

“The most important thing we have is that we fight for every ball, our sacrifice, our solidarity with each other, be together as one,” said assistant coach Ricardo Cortes before the tournament.

“That is all very important in order to put together a great team. Games are not won by individuals, but by teams.”

Chile have not won a game yet. They won’t win this one. But, the respect they have earned in battling defeats by Argentina and Japan doesn’t show on the scoreboard.

Points are not the prize for England either. Places, for the tougher Tests to come, are.