This piece was originally published on 24 September, 2020, 10 weeks before Peter Alliss died, at the age of 89.

With barely a pause for breath Peter Alliss is off, his mind and voice racing through memories of Ryder Cups few can now recall.

The wonderfully cheery 89-year-old admits he might not remember “every sneeze and bacon sandwich” but remains “incredibly proud” that his family is intrinsically linked with the history of the biennial match, that started as a contest between Great Britain and the United States in 1927.

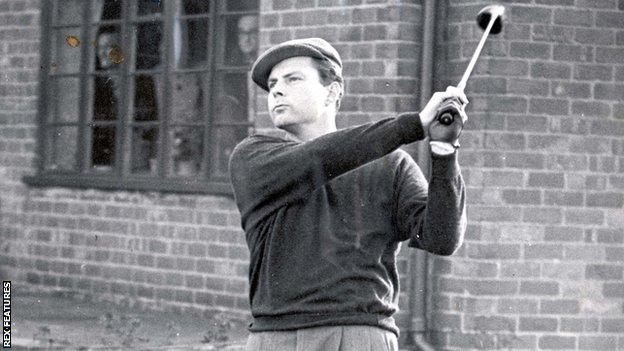

Peter was a stalwart of the Great Britain team so often whipped by the Americans through the 1950s and 60s, who then turned BBC commentator. His father Percy played in four editions between 1929 and 1937.

Percy and Peter Alliss were the first father and son to compete in the Ryder Cup and between them were involved in the only three wins the British team could muster in 23 matches, before European players were invited to the party in 1979.

This is the story of those wins – at Moortown in 1929, Southport & Ainsdale in 1933 and Lindrick in 1957.

It involves a club that had just four months to prepare to stage the matches and a bold teenager who ended up caddying for the Tiger Woods of his era; a club that hosted the tournament on a Monday and Tuesday to appease its members and almost became the home of the Ryder Cup; a Yorkshire businessman who stumped up £10,000 to rescue the event, and the first example of course manipulation to suit the British players.

The battle of the Moor – 1929

In April 1929, Walter Hagen arrived at Moortown in Leeds for the first Ryder Cup to be held in Britain. He was, quite simply, the biggest name in golf.

The flamboyant American had won 10 major championships. An 11th would follow a month later with victory at The Open at Muirfield. Only Jack Nicklaus, with 18, and 15-time champion Woods have won more.

The 36-year-old had led the American team to a crushing 9½-2½ victory in the inaugural Ryder Cup in Massachusetts in 1927.

But in a sign of the more relaxed atmosphere around the Ryder Cup back then, when ‘The Haig’ emerged from his car at Moortown – reports differ between it being a taxi or a Rolls Royce – he was approached by 16-year-old factory worker Ernest Hargreaves.

“I just walked right up and offered my services,” Ernest, who was also a caddie at the course, told reporters. “He said it would be alright.

“Later I asked him if he was fixed up for the Ryder Cup match, and again he said it would be alright.”

It would get better still for young Ernest.

Hagen asked the teenager to caddie for him at The Open, which was played two weeks later, in May. He won his fourth, and final, Claret Jug and gave his £75 prize money (worth around £4,700 today) to the “nice little boy”, who would go on to work for Henry Cotton.

It’s a story that is impossible to comprehend given today’s game, when caddies – and indeed whole entourages – are carefully selected by players, but as Alliss told me: “It’s hard to explain how different life and sport were back then.”

It is, predictably, far from the only difference. For instance, the next Ryder Cup to be held on European soil will be in Italy in 2023 – delayed by a year because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The Italian Golf Federation estimates it will cost them £127m to host the event in Rome, with sponsorship and ticket sales covering the outlay.

Back in 1929, Moortown member John L Kirby suggested club professionals across the country should ask their members for half-crown (12.5p) donations to help raise the £500 (worth about £32,000 today) needed to stage the event and fund the British team for future matches.

In return, they would get a ticket to watch the Ryder Cup.

And while there was opposition to paying an admission price, among suggestions it was ‘not in keeping with the dignity of the Professional Golfers Association’, the PGA itself said it was a case “where a ‘Yorkshire’ approach to matters of money was fully justified”.

That didn’t stop spectators hopping over walls for free but a report notes “members of the committee spent a zestful afternoon challenging those without badges and their efforts brought a few pounds to the till, plus a lively feeling of satisfaction to the collectors”.

Gate receipts totalled £1,810, plus around £800 from the half-crown contributions, resulting in the event making a profit that was enough to ensure the British team could defend the trophy in the US in 1931.

All of this was recounted to me by David Sheret, former captain and chairman of Moortown, who has written a comprehensive book on the event that he sells via the club to raise funds for its junior section.

“A pleasant surprise has come to golfing enthusiasts in Leeds,” was how, on 12 December, 1928 the Yorkshire Post opened its report announcing the second Ryder Cup was to be held at Moortown on 26-27 April, 1929.

It gave the club just four months to prepare – and winter months at that. In contrast, we already know the 2033 Ryder Cup will be held at Olympic Club, San Francisco.

“Can you imagine that now?” Sheret says as we sit in a Ryder Cup room that has a largely unchanged view of the 18th. “Kolin Robertson, a bank manager and Moortown member, approached the PGA and because we’d hosted other PGA events, it was more or less agreed on the spot.”

The opening salvos were fired early in the week, with Hagen confidently predicting: “I shall win. I always do.”

British captain Duncan was far from cowed though, saying: “Our golf is not so mechanical as that of the Americans. A machine has its limitations; it does not respond so readily as the mental and physical make-up of the human being to what I have called ‘urge’, and that is one of the reasons I confidently contemplate success in the ‘Battle of the Moor’.”

The Americans, who clearly had a more professional set-up, turned up with team outfits which Hagen described as “the finest dark blue knicker suits that you ever saw”. They also had “a sports outfit for lounge wear so that everyone will know us when we are off the links”.

When asked what the home players would be wearing, Duncan was characteristically blunt: “They will wear what they like. The Ryder Cup is a golf match and not a mannequin parade.”

And then it snowed.

It didn’t stop the Americans from practising but it was “jumpers and leather jackets”, rather than blue knicker suits on show.

The Americans were heavy favourites, with major winners Hagen, Gene Sarazen, Leo Diegel and Johnny Farrell among their 10 players, while 1920 Open champion Duncan was Britain’s sole major champion.

However, the visitors’ new steel-shafted clubs, while legal to use in the United States, were outlawed under R&A rules – the worldwide governors of the game outside the US and Mexico – so they had to have hickory clubs made and quickly relearn how to play with them. The R&A would approve the use of steel shafts later in 1929.

The two-day contest comprised of four foursomes (alternate shot) matches on the Friday and eight singles on the Saturday, all over 36 holes. With 12 points up for grabs, 6.5 were needed for victory. It would remain this way until 1961.

The Americans had brought a team of 10 over on HMS Mauritania and Hagen was determined to play all of them, while Duncan wanted eight players and dropped Percy Alliss and Stewart Burns, despite them having beaten Cotton and Charles Whitcombe in a practice round.

The Americans led 2½-1½ after day one, a day that had seen, according to one newspaper report, 10,000 spectators on the course.

“A thousand people were on the run down the first fairway…like the Charge of the Light Brigade”, is how another reported the excitement, with fans allowed a more free run of the course than today – although more ropes were used for crowd control on the following day.

Day two saw the captains play each other in the singles. Hagen wanted the challenge and after Duncan deliberately let it be known he would be the fourth out, the match was on.

Not that it was much of a contest. Duncan was five up after the morning 18 and completed a remarkable 10&8 rout to “wild enthusiasm” from the partisan home support.

Sarazen also suffered a surprise defeat, losing 6&4 to Archie Compston, while Whitcombe added a point with an 8&6 triumph over Farrell.

Aubrey Boomer, who somewhat remarkably reached the 586-yard par-five 10th (which is now the 12th) in two shots, picked up a fourth point, leaving just one needed from the other four matches for victory.

But Abe Mitchell, who was founder Ryder’s golf instructor and is the model for the figure adorning the top of the trophy, was thrashed by Diegel, while Horton Smith, who would go on to win the first Masters in 1934 and was the youngest player on either side at just 20, picked up a second point for the Americans.

Match seven was halved, leaving Cotton needing a half against Al Watrous to win the Ryder Cup.

The 22-year-old Englishman, who would go on to win three Open Championships, was well aware of the task facing him, saying afterwards that “people came up to me and told me if I won the cup was ours”. He completed a 4&3 victory amid jubilant scenes to make the final score 7-5.

The celebrations continued long into the night at the Queens Hotel in the centre of Leeds.

It was there, during the post-dinner speeches, that the normally dour Duncan had the last laugh. Recounting the set-up of his match with Hagen, the Scot said: “I told him I would be at number four and sure enough he came along. He sacrificed one match.”

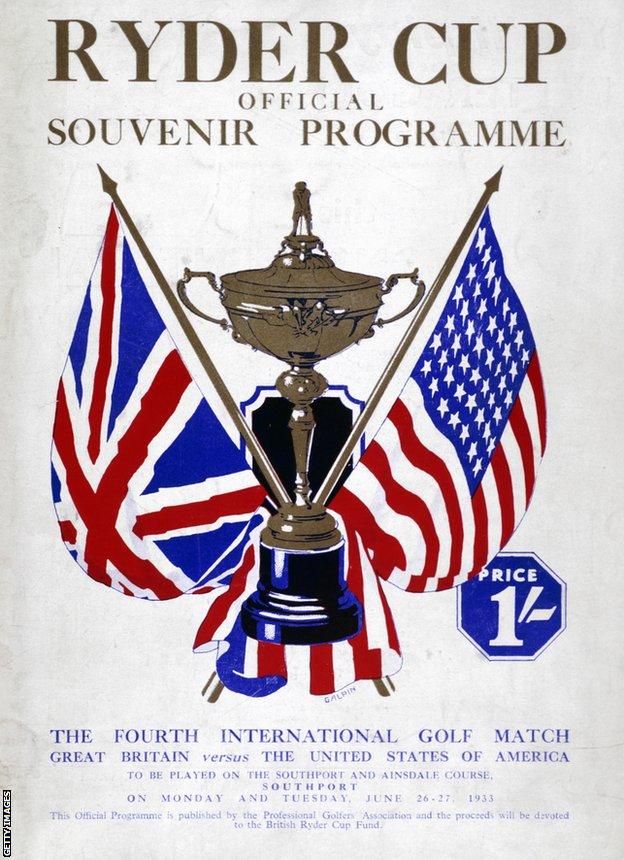

The narrowest of wins – 1933

The Americans gained their revenge in 1931 at Scioto Country Club, Ohio – the course that Nicklaus would learn to play on in the 1950s – with a thumping 9-3 win.

Two years later they asked if the next Ryder Cup in England could be played at Alwoodley, Moortown’s close neighbour which they had practised on in 1929 and liked. Alwoodley reportedly turned down the request because of “a lack of accommodation in the clubhouse”.

In any case, the PGA would have the final say and they were swayed by the enthusiastic support of Southport Borough Council, who had backed the Dunlop-Southport tournament – one of the biggest professional events of its day – and the feeling was there would be enough interest to attract a big crowd.

This area on the north-west coast of England is blessed with several outstanding courses and Southport & Ainsdale (S&A), Hesketh, Hillside and Birkdale (‘Royal’ status was still 19 years away) were in contention to be the host.

S&A got the nod in December 1932, partly because its sand dunes provided excellent vantage points and partly because of its transport links, with a railway station on its doorstep.

The date was set for 26-27 June, 1933 – a Monday and Tuesday.

“It was held on those days so it didn’t impinge upon the membership playing at the weekend,” says 83-year-old John Graham, an S&A member of 70 years, who still plays off a 14-handicap and had “nearly beat my age” the week before we met.

“The club had hosted several professional tournaments, so it appears it was a safe choice,” Graham adds.

“But professional golfers were not looked upon well by members back then. That’s not to say the club didn’t want to host the Ryder Cup, it’s just difficult to describe how professional sport was viewed.”

We are sitting in an atmospheric Ryder Cup room that features many wonderful reminders of the early days of this contest, and affords a gorgeous view down the exacting par-three opening hole.

“It’s 200 yards off the back tees and plays into the prevailing wind,” says Richard Kilshaw, general manager of S&A. “There are eight bunkers now and one at the front has been removed since the Ryder Cup.”

A fascinating video playing on loop also catches my eye. It’s Pathé News footage of the 1933 matches.

Hagen, again captain of the US side, almost smacks British captain John Henry Taylor flush in the chops with a practice swing on the first tee. Hagen laughs it off, saying “I wouldn’t dare to come that close to you”, while Taylor gives him an icy glare.

JH Taylor, recognised as a pioneer of modern golf, was a five-time Open champion and at the age of 62 the Ryder Cup’s first non-playing captain. He was chosen for his disciplinarian approach and a hope he could instil a level of professionalism to match that of the US team.

There’s also footage of a stymie being laid by British player Mitchell on Olin Dutra. The archaic practice, only allowed in matchplay, was eventually outlawed in 1952. It occurred when a player hit his ball inside his opponent’s on the green, in direct line with the hole.

The ball nearer the hole did not have to be marked if the two balls were more than six inches apart.

Dutra’s ball was only four feet from the hole but he was left with no option but to try and chip over Mitchell’s. He failed, knocking in his opponent’s ball to concede the hole.

Mitchell, who had also stymied Dutra in their foursomes match, went on to win the singles match 9&8.

The British side had led 2½-1½ after the foursomes and the singles were also tight with the US briefly moving ahead after victories for Hagen and Craig Wood.

Percy Alliss and Arthur Havers won their matches for Britain but Horton Smith levelled it up at 5½-5½ with only Syd Easterbrook, who had been a reserve, and Denny Shute left on the course.

It had been a real see-saw contest and they reached the 36th and final hole all square.

Shute had a four-foot putt to halve the hole, the match and therefore tie the overall scores. It would see the US retain the Ryder Cup as holders of the trophy.

He missed.

Easterbrook didn’t and the cup was regained 6½-5½.

A gracious Hagen said: “We are a trifle disappointed that we are not taking the cup back with us. We did tell the fellows on the Aquitania to reserve a place for it for the return journey.”

S&A hosted the Ryder Cup again in 1937, when the Americans became the first team to win away from home, and Graham says it would have been back again in 1941 had World War II not intervened.

“In fact, Southport came close to agreeing to be the home of the Ryder Cup,” he adds.

But, of course, the war did intervene, and while the US team continued to play Ryder Cup-style matches among themselves, there would not be another competitive meeting until 1947.

A home match for Britain – 1957

What turned out to be Britain’s final Ryder Cup victory – a 7½-4½ victory at Lindrick which ended a run of seven defeats – holds good and bad memories for Alliss.

“We should have won at Ganton in 1949,” he begins, picking up pace in his recollections.

“We were hopeful in the build-up to Lindrick… they closed the A57 road, which was a big thing… everybody on the home side overdid the celebrations… there were certain rules and regulations that, with the benefit of hindsight, were hysterical.”

When I stop him there and ask him to elaborate, Alliss says: “We were not allowed to bring our wives and girlfriends. The US arrived with their glamorous wives in fur coats and with diamond earrings and immediately we were two down before the first tee.”

The heathland course straddles the A57 that connects Sheffield with Worksop, and proudly boasts that paying members, Danny Willett, Lee Westwood and Matt Fitzpatrick all played in the 2016 Ryder Cup team.

Lindrick became the venue for the 12th Ryder Cup because of the generosity of Sheffield steel businessman and philanthropist Sir Stuart Goodwin.

“The Ryder Cup was not in great shape,” Lindrick archivist Graham Mann tells me. “Interest was low and there was no venue for the event until Goodwin persuaded the PGA and struck a deal with the Lindrick captain, leaving him to inform the club’s committee.

“Goodwin put in £10,000 and told the PGA they could keep the gate money, which came to just over £16,000 and the event, which was used to making a loss, returned a net profit of about £11,000.”

That profit should have been much higher according to Jeremy Mason, who was born “just off the back of the 13th hole” in the house of his grandad, the 1957 Lindrick captain AS Furniss.

“We’d barely heard of the Ryder Cup,” he says after joining us in Lindrick’s Ryder Cup room. “We weren’t expecting big crowds and a lot of people got in for free because we had little in the way of fencing.”

Just as at Moortown and S&A before them, Lindrick’s members were put on volunteering duties, helping with car park duties and as marshals helping spectators around the course.

In the end “thousands turned up and we went to battle on a delightful course”, says Alliss.

Despite the absence of major winners Sam Snead, Cary Middlecoff and Jimmy Demaret – who said he could have “picked a better team blindfolded” – American confidence was so high they had the trophy insured for the return journey before they set off.

However, contemporary reports suggest the course was, for the first time, “tricked up” to suit the British players, with narrow fairways, fast-running greens that were not watered for three days before the event, and rough through the back of them – known as jag grass.

This view is supported by Max Faulkner, the 1951 Open champion and the only major winner in the British team.

“By these three simple steps we made sure that it was really going to be a ‘home’ match for the British team, because these were the exact conditions under which we played most of our tournaments,” he said.

“I remember watching Jackie Burke, the US captain, trying to chip out of the jag grass on one of the practice days. He had one shot at it and moved it a foot, had another shot at it and moved it another foot and then picked up his ball in disgust.

“Burke made no attempt to find out how the shot should be played. I knew then that we had the match in our grasp.”

However, Faulkner, who accepted he was playing badly, asked to be dropped for the singles after Britain lost the day one foursomes 3-1.

But captain Dai Rees, according to Alliss, “was his usual ebullient self” and asked for the greens to be cut a little shorter for day two.

Six of the eight American players three-putted the first green in the singles.

It set the tone for a stirring British fightback.

Britain won the first five matches, with Welshman Rees and Ireland’s Christy O’Connor – who used a putter bought in the professional’s shop at lunch – romping to 7&6 victories. The team, while featuring many Irish players over the years, would not officially be called GB&I until 1973.

Ken Bousfield secured the winning point and while the celebrations began, Alliss said his cup was only “three-quarters full”.

“My sadness was I didn’t contribute a point,” says the eventual veteran of eight Ryder Cups.

“Max Faulkner ran across to tell me the news when I was one down with three to play and it knocked the stuffing out of me.

“I wasn’t really allowed to properly finish my match off.”

After the trophy presentation and a lot of “milling around” at Lindrick, the teams transferred to the Grand Hotel in Sheffield, where Alliss has “strong memories of lots of drunken speeches”.

“They went on and on and on and I recall looking across at the American team and thinking how shattered they all looked, but they stayed to the end.”

It would be the last British victory in the Ryder Cup. The next time the Americans would be beaten was in 1985 and by then Continental European players had bolstered the challenge from this side of the Atlantic.

All three courses on which Britain tasted victory are still ranked among the top 100 in England but, sadly, all three readily accept they will never again host a Ryder Cup in this vastly more commercial era.

Still, they are rightfully proud of the part they played in the formative years of the matches and offer great experiences for those keen to immerse themselves in the history of this wonderful event.

Hopefully they’ll keep talking about their place in history with just as much cheerfulness as Alliss.