Most British sports have a particular venue synonymous with their global reputation – Wembley for football, Lord’s for cricket, Wimbledon’s All England Club for tennis. Grand stadiums for big events.

What does it say about boxing that its most iconic UK venue is so different?

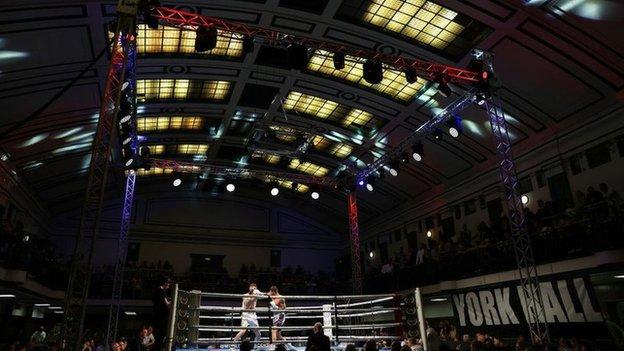

The York Hall on Old Ford Road, in Bethnal Green, east London holds only 1,250 people when packed out, making it a quintessential small hall. Yet it carries a special significance in the boxing scene. Anyone involved in the sport, whether as a fighter, trainer, manager, promoter or journalist, will have spent time there.

A York Hall show provided the setting for one of my early assignments as a boxing reporter more than a decade ago. The upper floor was closed that night, meaning the venue operated at half capacity. Even so, the intensity of the atmosphere was stirring.

After entering through the main hall’s doors, the ring loomed large, dominating the space. Even from the back of the room, it was apparent that not only were views superb from everywhere, but the high ceiling provided a special acoustic quality too. Crowd noise reverberated around the rafters, mingling with clouds of evaporated sweat. In quieter moments, you could hear the thud of punches landing, or the boxers’ grunts of effort. It felt deeply intimate in a way that someone who has only watched boxing on TV, or from the regular seats at a large venue, would be unable to understand.

I sat at the press table, which that night was right up against the ring apron. At one point during the evening, as I hunched over my notepad and pen, I was spattered with blood, which I believe came from the Irish heavyweight, Declan Timlin.

A baptism, of sorts.

Resonating with the past

The Japanese belief system known as Animism holds that all objects, including buildings, have souls. Since being opened by the Duke and Duchess of York in 1929, as a public baths, following the great public health legislation of the Victorian age, York Hall has encapsulated that.

Between World Wars One and Two, “going to the baths” carried a different meaning than it might today. Local baths were an essential part of public sanitation, rather than a place for recreational swimming and most working-class households, especially those in places such as the East End of London, did not have bathing or laundry facilities at home.

As a sport which has always embodied a very working-class character, it was perhaps appropriate that boxing promoters would come to find the venue attractive. Their target audience, after all, lived nearby and were accustomed to going there.

In a development typical of the era, York Hall’s first nights of professional boxing took place in the late 1940s, a period when the majority of London’s boxing shows took place in public baths. The bath itself would be boarded over and a ring constructed on top, while the room size would allow for enough ticket buying customers to turn a profit. In this way, York Hall was operating in a very similar way to a host of other nearby venues, such as Tottenham Baths, Manor Place Baths in Elephant and Castle or Lime Grove Baths in Hammersmith.

What makes York Hall unique is that while society and boxing have both since evolved, and television pulled the rug from under the feet of many forms of local entertainment, these other venues have gradually closed down, fallen into disrepair or been demolished. York Hall on the other hand, has somehow endured.

Resilience in the face of change

Despite housing swimming and gym facilities, alongside its boxing events, the building has survived a number of existential threats in addition to the general onset of modernity. In 2004, it was slated for closure by Tower Hamlets council, which described the venue as, “out of date”. It also said it was, “not acceptable for Tower Hamlets residents to subsidise people who travel in from the leafy shires to watch a boxing match and then go away again”.

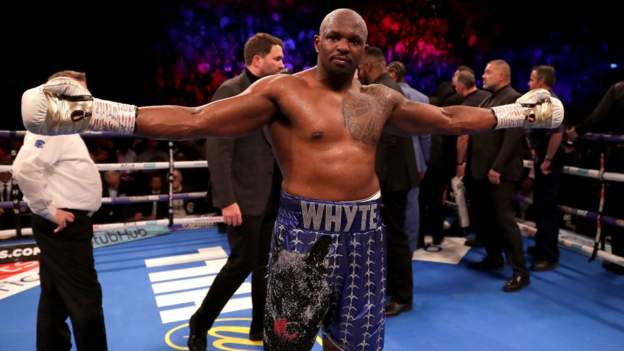

A campaign endorsed by promoters Frank Warren and Kellie Maloney, alongside celebrated ex-boxers such as former world champion Charlie Magri, proved successful. New backers were found, and the venue prevailed, going on to play a pivotal role in the early careers of hundreds of British fighters since, including David Haye, Carl Froch, Tyson Fury and Anthony Joshua.

As gentrification continues to change the face of east London beyond all recognition, York Hall’s stubborn survival gains poignancy. Its working-class origins may now feel more distant, while boxing, like everything else, has moved into the digital and pay-per-view era. Below the highest levels, small hall nights continue to be held up and down the country, often in modern leisure facilities or conference centres.

But York Hall offers something else. It provides the chance to watch and experience boxing in the same way as people would have done in the first part of the last century, raw, immediate and unaltered by the passage of time.

As the punches land, they echo the past.