In 30 years’ time, climate change may be making such an impact on sustainable water supplies, that lush wide-open fairways are a thing of the past.

We’ve imagined a 2050 golf tournament that feels a little more industrial…

A breathtaking eagle at the 18th hole – ricocheting in off the iconic cooling tower – saw China’s Zhang Min take a sensational win to become the inaugural champion of the Extreme World Golf Tour.

The dramatic climax to the Fiddler’s Ferry Power Station X-Open on Sunday was a fitting end to the new sport’s debut season.

Fans have been treated to some stunning urban golf played across punishing concrete landscapes as the traditional game moves into its new-look future away from lush grass courses.

Zhang, 22, hit some sublime golf shots throughout the weekend, and was oozing confidence having won the punishing Megawatt Valley X-Classic the previous week – the multi-course event of the Tour’s British leg, which took place on the site of former electricity sub-stations through the Trent Valley.

Her speed, accuracy and agility – all essential elements of urban golf, which has been compared to “parkour with a golf ball” by pundits – have seen her never fail to make the top 10 at any event on the Tour, which have included courses set in warehouses, industrial buildings, old farmland and even defunct sports stadiums.

She maintained her form at the tricky course around the decommissioned power plant in Warrington, taking 82 shots in 47 minutes to give her 129 and break the previous course record of 133 set by Rico Banks in 2041.

That included an eagle at the iconic final 18th hole, which ends beneath the last remaining standing cooling towers in the UK.

The towers were due to be demolished following the plant’s closure in 2020 but a successful campaign saw them listed by the UK government, protecting them from being blown up.

The structures, which are 375ft (114m) tall, mark the course as one of the country’s most notable but also one of its toughest, and a modest Zhang said she was stunned to have performed as she did.

“It’s so hard out here. You have got all the rubble and the broken concrete lying around which can send your ball anywhere when it lands, so I had a lot of luck today,” she said.

“When you think you are landing in the long grass you could just as easily be hitting water and not know, it’s so boggy out there on the outer holes. So, yeah, I had a lot of luck. When they gave me my score I couldn’t believe it.

“And to beat Rico’s record is amazing. He was a real pioneer who did so many good things to get our sport into the mainstream.”

Scotland’s Seri Yoshiyama was the highest-placed Briton at Fiddler’s, the 39-year-old finishing eighth with 151.

“I thought I was going to break 150 again because I got round quickly but you can’t win when you take more than 100 shots,” said the disappointed veteran.

Russell Seymour is founder and chief executive of the British Association for Sustainable Sport

This story shows how sport, specifically golf, might adapt to changing environmental and climatic conditions. Unpredictable weather will make it harder to manage and maintain courses.

In some areas of the world this may be due to drought and water scarcity, while in others it may be rain and storms. Already some links courses are facing physical incursions on to the course due to coastal erosion.

While greenkeepers are knowledgeable and adaptable and can work on tees, fairways and greens, increased frequency of poor weather (which could include extreme heat as well as wind, rain and storms) may make it less attractive and, perhaps at times, even dangerous to play.

It’s unfortunate that, in the not-too-distant future, many golf courses may struggle financially as the playing time available to recreational players, the life-blood of most clubs, reduces. If opportunity declines it seems likely that the number of people playing ‘traditional’ golf may also decline.

As human population increases and the economy becomes more localised, it is also conceivable that land use pressures may switch to growing food, rather than for leisure so golf courses become fields.

But sport always adapts.

At the same time that traditional golf may decline due to climate disruption and land use changes much of the industrial infrastructure that has dominated our skylines and energy production for decades will be decommissioned.

Similarly, large structures such as office blocks and even sports stadia may become uninsurable, and so no longer viable, if they suffer from repeated storm damage, leading to their abandonment and decline.

The story finds a productive use for these abandoned industrial sites as urban parks and leisure facilities. It imagines the new sport of Extreme Golf that utilises these urban landscapes in a new, fast format of the great old game.

Matt McGrath is the environment correspondent for BBC News

While Donald Trump was generally sceptical about climate change, he was happy to believe in the concept when it came to one of his golf courses in Doonbeg in Ireland.

An application from the Trump organisation to build a sea wall to protect the course cited the threat from coastal erosion linked to climate change.

The former US President isn’t alone in appreciating the threat from rising seas.

Many scientists believe sea level to be the most powerful human impact of a changing climate.

Recent research suggests around 200 million people around the world will be living below the sea level line by 2100.

The warming world affects the seas in a number of ways.

The more obvious ones are the melting of glaciers and the massive ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica.

The lesser known but most important aspect is the thermal expansion of water – as in a boiling kettle, the warmer the water gets the more it expands.

Between 1993 and 2010 thermal expansion was responsible for about a third of the recorded rise in sea level.

For golf, the rising waters threaten many of the finest courses around the world.

Montrose Golf Links in Scotland is one of the world’s oldest, dating back around 450 years.

But the seas are no respecter of tradition and the course is losing around 1.5 metres every year.

It may not sound like much but the owners fear for the long-term survival of the links if financial support for coastal protection is not forthcoming.

As well as the threat from erosion, golf courses may struggle to keep their lush green hues in a world with rising temperatures.

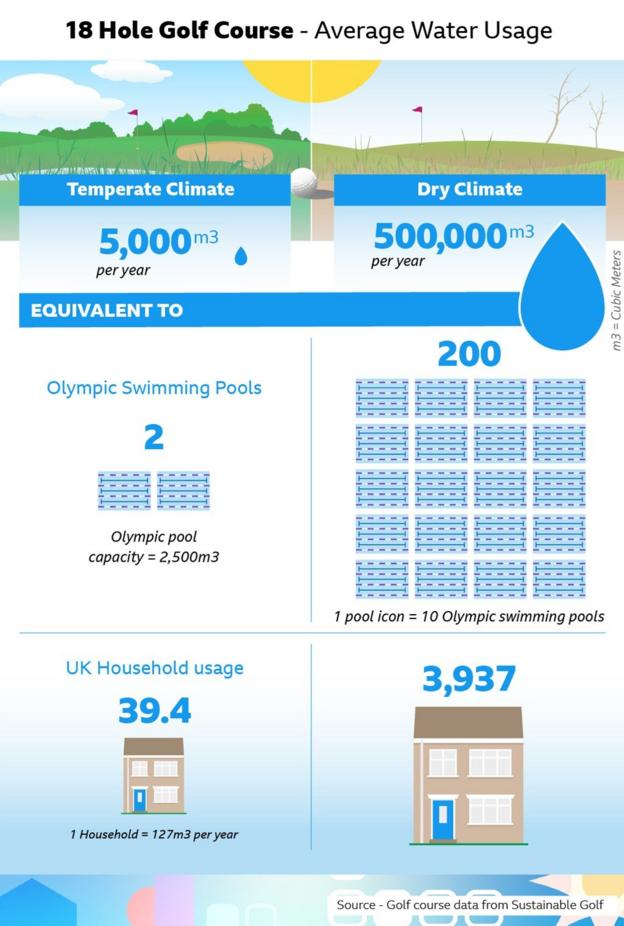

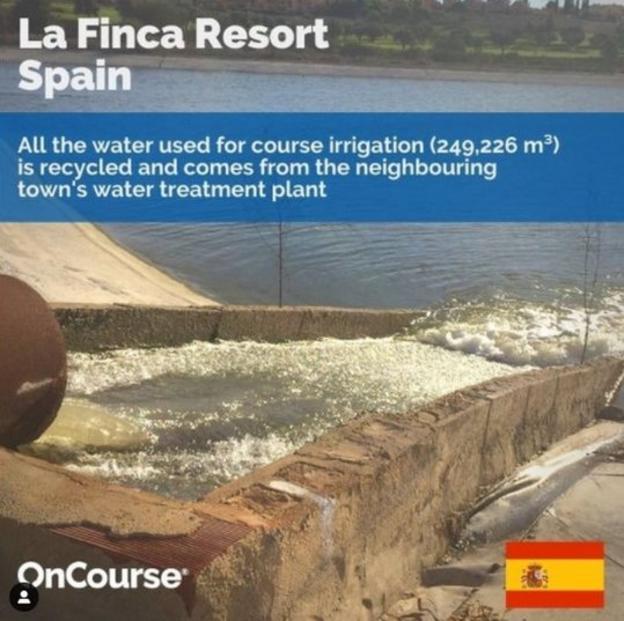

Water is one of the big problems for golf. In 2018 the Cape Town Open moved further inland to due to drought – and there is a great deal of work under way to try to reduce the amount used.

Some courses are responding by looking to grow warm-season grasses on their fairways.

While these look off-colour in the winter, the grass is more tolerant of hot weather and reduces water consumption.

Radical solutions include cutting the number of holes on a course from 18 to nine.

One course in Vietnam has a 6.5 hectare (17 acre) rice field running through the middle of the property, that produced a 28-tonne crop in 2020.

This type of endeavour, which supports the local community and helps protect the environment, may well be the key to the future survival of the game in a much hotter world.