| Venue: Edgbaston Dates: 16-20 June |

| Coverage: Live text commentary and in-play video clips on the BBC Sport website & app, plus BBC Test Match Special on BBC Sounds and BBC Radio 5 Sports Extra. Daily Today at the Test highlights on BBC Two and BBC iPlayer from 19:00 BST. |

“Will England’s style of play work against Australia?” is a question being asked so often, Ben Stokes is fed up of answering it.

Naturally, it is a huge factor in determining the eventual destination of the Ashes urn, but it is not the only way the winners of cricket’s most storied contest will be decided.

With the help of Cricviz, BBC Sport has taken a closer look at all the key battlegrounds.

Can England ‘Bazball’ the Australian attack?

The most obvious place to start.

England’s upturn in fortunes under captain Stokes and coach Brendon McCullum has been built on some breathtaking batting that has laid waste to attacks in Manchester, Multan and Mount Maunganui.

In the 13 Tests England have played since Stokes and McCullum took over last year, they have scored their runs at 4.85 an over, more than a whole run faster than the next swiftest scorers – Australia on 3.56.

Their most notable achievements include chasing 299 in 50 overs to beat New Zealand at Trent Bridge, knocking off 378 inside 77 overs to defeat India on the same Edgbaston ground that will host Friday’s Ashes opener, then piling on 506-4 on a stunning first day against Pakistan in Rawalpindi.

| Length | Average | Strike-rate |

| Full | 41.30 | 94 |

| Good | 33.06 | 52 |

| Short | 43.04 | 85 |

England’s swashbuckling style is most likely to work when the ball moves least. At home last summer, the birth of Bazball was certainly helped by some very flat pitches and a batch of Dukes cricket balls that quickly went soft and out of shape.

In fact, over the course of last summer’s seven home Tests, there was on average less seam and swing movement in the first 20 overs of an innings than any of the previous five years, bar 2019.

In a small sample size of two Tests so far this summer (England v Ireland and Australia v India), the news is good for England – the swing and seam has reduced when compared to last year. In theory, that means even better conditions for their batters.

| Year | Average swing | Average deviance |

| 2018 | 1.30° | 0.84° |

| 2019 | 0.73° | 0.79° |

| 2020 | 0.95° | 0.74° |

| 2021 | 1.26° | 0.73° |

| 2022 | 0.87° | 0.70° |

| 2023 | 0.75° | 0.56° |

The greater variable is the arrival of the Australian attack, probably the best in the world. Can England get after Pat Cummins and co?

In the Stokes-McCullum era, England’s batting hasn’t been about recklessness, but a complete commitment to positive intent. They miss no opportunity to score, pouncing on the slightest mistake from a bowler.

It comes as no surprise to learn England are kept most honest by pace bowlers who can hold a good length.

Over the course of the past year, a good length (pitching 6-8m in front of the batter) has England averaging 33.06 and striking at 52 runs per 100 balls.

When bowlers have gone too full, the average rises to 41 and strike-rate to 94. Too short and those numbers become 43 and 85.

If, then, Australia are looking for their attack to hold a length, Scott Boland has to be in their XI.

The 34-year-old, who made such an impact on the last Ashes and displayed his impressive talents in the World Test Championship final, has bowled 53% of deliveries in his Test career on a good length – a higher percentage than any other bowler in the world since 2006 (when the data began).

Josh Hazlewood (43%) and Cummins (36%) are Australia’s next most prolific length bowlers.

Unsurprisingly, the often-wayward Mitchell Starc, who went at more than five runs an over in each innings of the Test Championship final, is the least likely to bowl a good length, with a career percentage of 29%.

The conditions look to be in England’s favour and they must hope Australia overlook Boland.

| Full % | Good % | Short % | |

| S Boland | 19 | 53 | 28 |

| J Hazlewood | 35 | 43 | 22 |

| P Cummins | 23 | 36 | 41 |

| C Green | 29 | 31 | 40 |

| M Starc | 38 | 29 | 33 |

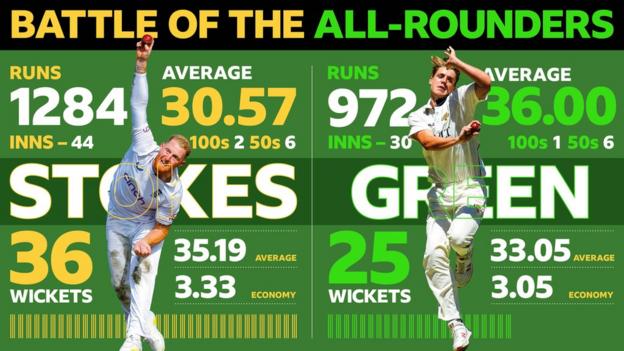

Battle of the all-rounders

Despite England being behind in overall Ashes contests – Australia have won more Tests and series – the Poms have always been used to having the premier all-rounder on either side.

In the past 70 years, there have been 14 instances of a player scoring at least 250 runs and taking 10 or more wickets in an Ashes series. Only one of them, Steve Waugh in 1986-87, is Australian.

Stokes has done it once, his debut series of 2013-14 (despite his epic Headingley innings four years ago, he only took eight wickets in the series) and now has a rival for the crown of leading Ashes all-rounder.

Since Cameron Green made his Test debut in December 2020, he has had a better batting and bowling average than Stokes. Australia have lost only three Tests of the 21 Green has played in. He’s like having three men in the gully, too.

Questions over Stokes’ left knee linger, meaning England do not know if they will have a fully fit five-man attack.

For the first time in years, Australia have ideal balance in their side through the huge shape of Green.

Still, what remains immeasurable is Stokes’ impact as England captain. That itself could be enough to win England the Ashes.

Open door?

Though both sides have a regular opening partnership, all four men who will bat at the top of the order in the first Test at Edgbaston have questions hanging over them.

For England, Ben Duckett has been prolific since being recalled in December, but his eagerness to attack outside the off stump will be severely tested.

Zak Crawley ended a run of eight innings without a half-century against Ireland, but a large chunk of his 56 came via the inside edge.

David Warner and Usman Khawaja are the first pair of Australian openers aged over 36 since 1926.

Warner, who is on the road to retirement, averaged just 9.5 here four years ago, while Khawaja, in great form for the past 18 months, only averages 17.78 in England.

Still, the truth is that recent series have shown a solid opening partnership is not a necessity for winning an Ashes series in the UK.

Since 2001, the last time Australia won here, Justin Langer’s 55 is the best average by an opener on either side. Langer played six Tests, five of which were in 2005, a series Australia lost. The next best is Chris Rogers’ 50 and he won neither of his two series.

On the flip side, England legend Alastair Cook won all of his three home Ashes series at the top of the order, but averaged less than 30.

In that 22-year timespan, the average of an opening batter in Ashes Tests in the UK is 33.36. Incredibly, openers for the losing team over the same period have a higher average than winners – 38 v 35.

Conclusion? Openers have not had a significant impact on the result of Ashes series in the UK.

If one of Crawley, Duckett, Warner or Khawaja can stand up, it will give their team a huge and historically unlikely boost.

The immovable objects

Somehow, England have to find a way through Australia’s middle order.

First comes Marnus Labuschagne, ranked as the world’s number one Test batter, followed by Steve Smith, on course to becoming the most prolific Ashes run-getter since Don Bradman.

At five is Travis Head, averaging more than both Labuschagne and Smith since the last Ashes, when he was player of the series.

Taking them one by one, there are certain plans England could consider for Australia’s terrific trio.

Across his Test career, Labuschagne has been weakest against deliveries bowled on a ‘hard’ length, pitching 8-10m in front on him, and moving away off the seam. Six times Labuschagne has met his demise to such deliveries, averaging only 29.

In addition, Labuschagne has shown a weakness to high pace, falling nine times to deliveries of speed in excess of 140kph. In the last Ashes in Australia, Mark Wood got Labuschagne three times at an average of 37, well down on his career mark of 57.

If high pace could be the way to go against Labuschagne, then Smith thrives when the heat is turned to the max, averaging 62 against the very fastest bowlers.

England have tried umpteen plans against Smith, but are more likely to find success on a good length with the ball moving back towards him. In England, these types of delivery bring his average down to 19.

His Sussex team-mate Ollie Robinson would be the best bowler to execute such a plan – the nip-backer is his most frequent mode of dismissal in Test cricket. Remarkably, in the last Ashes Robinson dismissed Smith twice for the cost of just 18 runs.

Anyone who watched Head bat in the World Test Championship final will have seen his compulsion to attack the short ball.

In his Test career, Head has played a false shot 31% of the time to short-pitched bowling, way above the 23% average for a top-seven batter. His dismissal rate to short-pitched bowling is much more frequent than the rest of his Australian team-mates, too.

In Wood, England have a dangerous exponent of bouncers – only South African pair Anrich Nortje and Kagiso Rabada have taken more wickets with bumpers since the beginning of 2021.

With Wood unlikely unable to play all five Tests, England could turn to Josh Tongue. More than half of the deliveries he bowled on Test debut against Ireland were short-pitched.

Spin war

Nathan Lyon and Moeen Ali might be on opposing sides, but the two spinners will be united in knowing they will come under attack.

Moeen admitted as much when he spoke to the media on Tuesday, while Lyon will have seen the way England have pummelled spin in the Stokes-McCullum era.

The clear difference is the way they enter the series. Only seven men in history have taken more than Lyon’s 487 Test wickets.

Moeen, on the other hand, has ended a near-two-year Test retirement to fill the void left by the injured Jack Leach.

He should have been on holiday in the Cotswolds and on Wednesday will miss training in order to collect his OBE.

Four years ago, Moeen was hit out of the series after only one Test. His career average against Australia is almost 65, his strike-rate in excess of 100.

One thing that may prepare Moeen for the Aussie onslaught in his experience in white-ball cricket. Still, in Tests since 2018, he concedes 6.62 runs an over when batters advance down the pitch, compared to Lyon’s 5.81.

Even when batters sit on the back foot and look to milk the spin, Moeen remains more expensive, conceding 3.73 to Lyon’s 2.05.

Still, England won’t be concerned about the runs Moeen leaks if he is taking wickets. That is where he has an advantage over Lyon, with a career strike-rate of 60.7 compared to 63.7.

The spinners know they are an endangered species in this Ashes. They must kill or be killed.

And a simple fact

If all of this sounds a bit too in-depth, there’s every chance that it is, so perhaps it’s best to end on a very simple thought.

In 71 series played between England and Australia, 37 have been won by the team that has won the first Test.

The last time a team lost the Ashes opener and went on to win the series was England’s legendary success in 2005.

In the nine series since, six times the team that won the first Test lifted the urn.

In short, the winners of Friday’s first Test at Edgbaston are very likely to be holding the Ashes aloft at The Oval at the end of July.