Cycling’s governing body, the UCI, has toughened its rules on transgender eligibility by doubling the period of time before a rider transitioning from male to female can compete.

Previous regulations required riders to have had testosterone levels below five nanomoles per litre (nmol/L) for a 12-month period prior to competition.

The UCI has changed the permitted level to 2.5 nmol/L for a 24-month period.

It says the new rules have been brought in following “new scientific studies”.

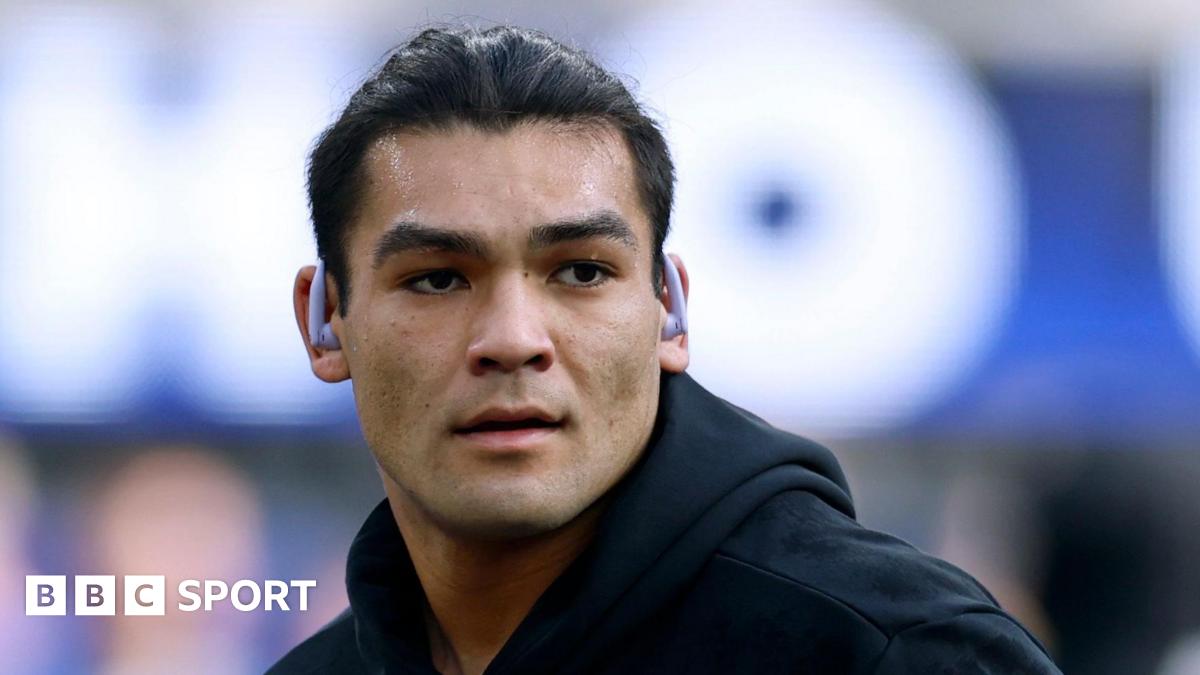

The UCI’s transgender policy had been under review after being brought into the spotlight by British rider Emily Bridges, one of cycling’s most high-profile transgender competitors.

In April, the 21-year-old – who began hormone therapy in 2021 as part of her gender dysphoria treatment – was stopped from competing in her first elite women’s race by the UCI.

The world governing body said that Bridges’ participation could only be allowed once her eligibility to race in international competitions was confirmed.

British Cycling also suspended its current policy, meaning transgender women are currently unable to compete at elite female events run by the organisation.

The UCI said scientific studies had shown that it can take as long as two years for muscle strength and power to adapt to a “female level” while 2.5 nmol/L “corresponds to the maximum testosterone level found in 99.99% of the female population”.

In a statement, the UCI said: “The latest scientific publications clearly demonstrate that the return of markers of endurance capacity to ‘female level’ occurs within six to eight months under low blood testosterone, while the awaited adaptations in muscle mass and muscle strength/power take much longer [two years minimum according to a recent study).

“Given the important role played by muscle strength and power in cycling performance, the UCI has decided to increase the transition period on low testosterone from 12 to 24 months.”

The new rules come into effect from 1 July and mean that Bridges will not be able to compete in women’s races until 2023.

The UCI said its rules could evolve based on further scientific research and added that it would like to start a research programme across several sports into the effects of hormone therapy.

“This adjustment of the UCI’s eligibility rules is based on the state of scientific knowledge published to date in this area and is intended to promote the integration of transgender athletes into competitive sport, while maintaining fairness, equal opportunities and the safety of competitions. The new rules will come into force on 1st July. They may change in the future as scientific knowledge evolves,” added the UCI statement.

“Moreover, the UCI envisages discussions with other international federations about the possibility of supporting a research programme whose objective would be to study the evolution of the physical performance of highly trained athletes under transitional hormone treatment.”

A polarising debate around inclusion

Many argue that transgender women should not compete in elite women’s sport because of any advantages they may retain – but others argue that sport should be more inclusive.

The debate centres around the balance of inclusion, sporting fairness and safety in women’s sport – essentially, whether trans women can compete in female categories without an unfair advantage.

The International Olympic Committee’s framework on transgender athletes – released in November – states that there should be no assumption that a transgender athlete automatically has an unfair advantage in female sporting events, and places responsibility on individual federations to determine eligibility criteria in their sport.

In an interview with DIVA magazine last month, Bridges said she “does not have any advantage” over her competitors, and can prove it with data.

She said that “a lot of people still view trans women as men with male anatomies and physiologies” but that “hormone replacement therapy has such a massive effect. The aerobic performance difference is gone after about four months.

“There are studies going on for trans women in sport. I’m doing one and the performance drop-off that I’ve seen is massive. I don’t have any advantage over my competitors and I’ve got data to back that up.”

This view is disputed by some sports scientists, who say the physiological differences established during puberty can create “significant performance advantages [between men and women]”.