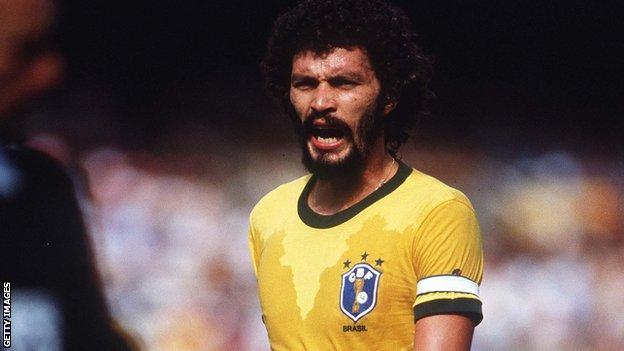

In November 2004, Brazilian football legend Socrates made a famous (and short) promotional cameo for English non-league side Garforth Town. As the football correspondent for a leading Brazilian newspaper, I arrived in the West Yorkshire town to write about the madness of it all.

An interview with the legendary midfielder – known as The Doctor because of his medical degree but also his political engagement – turned into a long after-hours chat at a local pub. Guards and notepads were down as Socrates, always a laid-back character, chatted about football with a sincerity that was remarkable even for him.

It was at that pub, such an unusual setting and so far from his comfort zone, that Socrates made a striking admission: he had never watched back Brazil’s 3-2 defeat by Italy in the 1982 World Cup – none of it. He just couldn’t bear to.

“I just don’t need to go through that game again,” he said. And it is quite likely that refusal remained until January 2011, when he died at the age of 57.

“That game” was a World Cup classic played on a hot Barcelona afternoon 40 years ago. One of the most feted generations of Brazilian footballers saw their dreams shattered by an Italian side that transformed over the tournament, putting a stuttering start behind them on the way to demolishing West Germany in the final.

With the passing of time, many older Brazilian fans have mellowed, but on 5 July 1982 the feeling was that a crime against football had been committed.

In 1982, Brazil was still ruled by the military regime that had seized power 18 years earlier, when left-wing president Joao Goulart was ousted in a coup.

Joao Figueiredo, an Army general, had become president in 1979 with the mission of overseeing a smooth return to democratic ways, but there were increasing calls for a faster handover during what was a turbulent time for the Brazilian economy.

It was in this context that Tele Santana was announced as the new Brazil football manager in early 1980. Santana had been a good player – a winger who scored 164 goals in nine years with Rio de Janeiro side Fluminense. He still ranks as their fourth-highest scorer.

Santana also built a reputation for fair play. He had never been sent off in his 12-year professional career. He demanded the same attitude from his players.

Qualifiers for the 1982 World Cup in Spain started with scrappy 1-0 and 2-1 away wins over Venezuela and Bolivia, but Brazil soon hit an impressive stride in the home games, beating the same opponents 5-0 and 3-1. In a May 1981 European tour, they raised eyebrows by beating England, France and Germany in the space of a few days.

But Brazil were doing more than winning. They were playing a fluid game that could not have been more different to the tactically disciplined style that had infuriated fans in the post-Pele era.

The exploits of Pele and Brazil at the 1970 World Cup had seemed like a long forgotten dream during uninspired campaigns in the two following tournaments, despite the team finishing in the last four on both occasions.

Now, as well as Socrates, the Selecao had Zico, the mercurial Flamengo playmaker, pulling the reins. Theirs was a flowing brand of football where no player seemed to touch the ball more than twice before passing it round. It was great to watch and, according to Zico, it felt even greater to play.

“We were adamant Brazil had to abide by the style that had made it famous. It would be wrong from the start to be scared of losing or to be a hostage of the result,” he says.

“We wanted to enjoy what we were doing. We felt that something really special was going on.”

So did millions of Brazilians. In the streets, bunting was going up as if in preparation for a royal wedding or a coronation. At a time during which Brazilian players were mostly plying their trade domestically – Roma’s Falcao a rare exception – you might bump into an international star on a trip to a Rio supermarket.

“Supporters would never hold back from giving us an earful, but at least they identified with us because we were all playing in Brazil at the time,” Zico says.

“These days players pretty much jump on a plane and fly abroad almost immediately after they play with the national team in Brazil.”

Expectations around the team were understandably high, and in Spain Brazil opened their World Cup campaign with a dramatic 2-1 win over the Soviet Union before thrashing Scotland 4-1 and New Zealand 4-0.

The tournament started with 24 teams in six groups of four. The six group winners and runners-up went through to a second group stage. The four winners of those groups of three would contest the semi-finals.

Brazil found themselves in the company of regional rivals Argentina and an Italy side that had drawn all three of their first-round games, barely making it out of a group that featured Poland, Cameroon and Peru.

Italy’s build-up to the tournament had been defined by the situation surrounding striker Paolo Rossi. In 1980 Rossi was involved in a match-fixing scandal and his two-year suspension ended only eight weeks before the start of the World Cup. Manager Enzo Bearzot nonetheless included the Juventus striker in his squad.

Coverage in the country’s media and the attitude of fans made for a sombre mood when they lined up to play Argentina on 29 June. Ninety minutes later they had won their first match in Spain. When Argentina were then put to the sword by Brazil in a blistering 3-1 win, the scene was set for a decisive showdown between two playing styles that couldn’t be more contrasting.

“You play there. Is there anything you want to say?”

Santana fired this question at the end of a team talk in Barcelona. Falcao was already anxious about the winner-takes-all game to be played against Italy at Espanyol’s now demolished Sarria stadium.

The Roma midfielder would be facing well-known opponents, and he feared his Brazil team-mates had the wrong idea about the real danger they presented, because of their stumbling start.

When prompted by the manager, Falcao expressed his worry about the possible role of Italian left-back Antonio Cabrini, a skilful player who was quite handy in attack. And that defender Claudio Gentile would probably stick to Zico like glue, aiming to repeat what he had achieved against a certain Diego Maradona in the previous game.

Italy’s was a style of play that could be placed in total opposition to Brazil’s adventurous commitment in attack. They knew how to close down and counter opponents – victory over Argentina showed it, a victory that revitalised them – but they would need to fire up front, too, in order to overcome the Brazilians. And their main striker Rossi had yet to score in the competition.

“That Brazil side wasn’t from this planet,” Rossi told me in 2006. “It had players who could pass the ball blindfolded.

“As for me, it just felt I was learning to play again after the suspension.”

In the Brazil camp, the mood couldn’t be more different.

“Some of the lads were teasing me and saying it must have been quite easy to earn a living in Serie A,” Falcao says.

Defender Oscar would later remember that some players were already discussing the weaknesses and strengths of Poland, the opponents waiting in the semi-finals.

Brazil would qualify with a draw – for they had a better goal difference – but Zico recalls: “In the dressing room before the game, Tele (Santana) never told us to hold back. Our commitment was always to go for the win, that was the true Brazilian way.”

Much of the crowd in Barcelona had not yet even found their seats when Cabrini whipped a cross and Rossi headed in. With five minutes gone, Italy were 1-0 up and Rossi had broken his duck.

Brazil hit back shortly after through Socrates, but fell behind again in the 25th minute when Rossi latched on to a woeful loose ball in the Brazilian backline. When they equalised once more in the 68th minute, Falcao’s screaming celebration was not only a reflection of joy but also the urgency of almost choking on his chewing gum.

At 2-2, Brazil had the result they needed to progress. But with a little over a quarter of an hour to go, from an Italian corner won against the run of play, Rossi got his hat-trick. Israeli referee Abraham Klein then wrongfully disallowed another Italian goal for offside before blowing the final whistle on what would be forever known in Brazil as the “Sarria Tragedy”.

Its legacy can be seen in the more pragmatic and physical styles that would become more popular in the country over the next generation. When Brazil beat Italy on penalties to win the 1994 World Cup, nobody could say they played with the same swagger.

Italy, meanwhile, followed the upset in Barcelona by beating Poland in the semi-finals with a Rossi brace before winning their third world title by overcoming West Germany in Madrid. The formerly disgraced striker, who died in 2020 at the age of 64, also scored in the final (3-1) and took home the Golden Boot.

“We were obviously saddened by the result against Italy but everybody had clear consciences,” Zico recalls.

“There is nothing wrong in losing with dignity, it is a part of the game. The Selecao was going home but we had stood by our convictions until the end.”

Falcao, who observed the 20th anniversary of the match by publishing a book of recollections of the 1982 campaign, also puts on a brave face when looking back.

“That team lost that game but won a place in history. I am grateful to have been part of one the greatest World Cup matches,” he says.

But some of the team felt defeat more deeply, few people more so than Socrates.

Twenty-two years after the events in Barcelona, on a cold night in West Yorkshire, he was still struggling to come to terms with it.

“We had a hell of a team and played with happiness,” he said, barely raising his eyes from the pint glass he was holding.

“Then Rossi had three touches and scored a hat-trick. Football as we know it died on that day.”